Last updated: January 14, 2026

Article

“Down but Not Out: USS RALPH TALBOT at Savo Island”

For 174 years, the Charlestown Navy Yard serviced the US Navy in many ways. Dockyard laborers in construction, repair, and refitting of ships played a key role at the Navy Yard as the nation struggled with conflict both home and abroad. One such ship they built in the yard played its own role during the country’s turbulent history. Though not as storied as Boston's USS Constitution, this vessel created during the Great Depression gave its all as a true workhorse for the fleet.

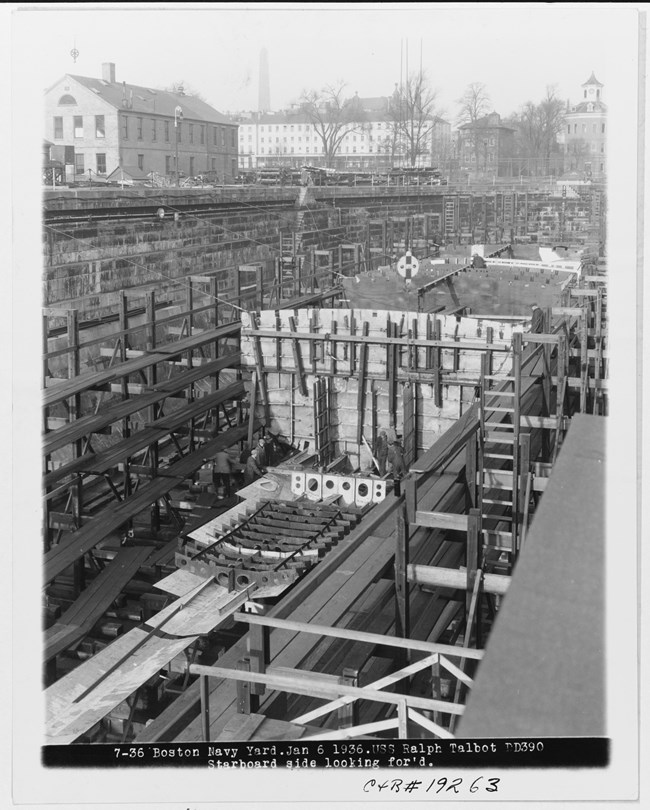

Constructing USS Ralph Talbot

During New England's autumn of 1935, two new naval ships began construction. October was in its final week as the yard observed Navy Day. A gathered crowd watched at Dry Dock One as the keels of the two ships were laid. With compressed air hammer in hand, Commandant of the First Naval District, Rear Admiral Walter Gherardi; drove the first rivet into the keel plates, or the bottom of the ship, to start building.[1] Among the crowd was Mrs. Mary Talbot from South Weymouth. Her presence gave a pointedly personal meaning to the ceremonies, for the ship being built was to be named after her fallen son. Second Lieutenant Ralph Talbot had been an aviator with the US Marines Reserve Flying Corps. He showed exceptional bravery on the Western Front during the First World War, sadly losing his life in a crash just weeks before the armistice. His heroism was recognized with a posthumous Medal of Honor. Along with a relative of the other destroyer’s namesake, Mrs. Talbot tossed dimes into the dry dock just before the first rivets were driven. Placed under the keel plates, they were meant to be tokens of good luck.[2]

National Archives, Naval History and Heritage Command, 19-N-19261.

National Archives, Naval History and Heritage Command, 19-N-19263.

It took a little over a year for the destroyer to be ready for launch, standard for peacetime construction. As in the previous October, Mrs. Talbot served as the guest of honor to christen the new vessel. It was as poignant as it was altering for the Navy, for it usually reserved such action for former officers of distinguished rank.[3] Other changes went deeper, as it was the first time in naval records that the mother of a ship’s namesake was alive for the christening.[4]

Nor was Mrs. Talbot the only person with ties to the fallen aviator. At her request, Colgate W. Darden was summoned to attend the launching ceremony in Boston. A Democratic Representative from Virginia, Darden, a fellow U.S. Marine, had been on the fateful flight with Ralph Talbot. While the young lieutenant had lost his life that October day, Darden had survived with serious injuries. Both veteran and mother attended the ceremony as the vessel was launched on October 31.[5] Mrs. Talbot herself broke the bottle over the bow of the destroyer which now held her late son's name, USS Ralph Talbot (DD-390).

National Archives, Naval History and Heritage Command, 19-N-19249.

National Archives, Naval History and Heritage Command, 19-N-19250.

Such an event did not come without words of warning. Massachusetts Senator David Walsh spoke to a crowd of 5,000 people about future conflict. The politician directed the ire of his speech to the civil war in Spain and communism.[6] Even so, the growing turbulence in Europe and America's lack of readiness were both evident with his words, "A new and devastating war is about to commence and our armies are reduced to a mere police force."[7]

Fully commissioned by the fall of 1936, Ralph Talbot became one of the new Bagley-class of destroyers. Over 2,200 tons fully loaded and with four five-inch guns, it was larger and stronger than the old Clemson's built after World War I. Similar to all destroyers, Ralph Talbot's teeth came in the form of 12 torpedo tubes. A little over 150 officers and enlisted crew lived within the 341-foot length of the ship, with room for more during time of war.[8] All the destroyer’s firepower and crew's bravery would be needed in the coming years. Though at peace during construction, both Talbot and its sailors soon faced the storms of war.

NavSource Naval History, 0539037

National Archives, Naval History and Heritage Command, 19-N-19242.

Pearl Harbor

Sunday, December 7, 1941 found the destroyer in anchorage with much of the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. Through the chaos and confusion as the capital ships at Battleship Row were set upon, the crew of Ralph Talbot snapped to their duties. Though taken by surprise, the sailors soon had the ship's main guns and .50 caliber machine guns in action. By the raid’s end, 150 rounds of the main battery had been fired, while the machine guns spat out 1,500 more. One of the young sailors commended was Seaman Second Class Robert Marshall. New to the ship, he was down in the handling room for one of the 5-inch guns when a shell dropped from the rack. His arms full, the young sailor used his foot to stop the fall before the 50-pound shell hit the deck. Despite the day's toll, Ralph Talbot emerged from the devastation at Pearl Harbor without damage or death to its crew.[9]

In the Pacific

With the United States fully involved in war, the Boston-built destroyer soon took up its duties. What capital ships remained needed to be escorted; this included the valuable aircraft carriers. Threats below, on, and above the waves made the destroyer the workhorse it was designed to be. As 1941 slogged into 1942, Ralph Talbot and its crew performed all those duties. In the background, fighting across the Pacific raged on. Slowly, the U.S. Navy and its allies began recovering from the hammer blows of Imperial Japan's push into allied territories. The disastrous fighting in the Java Sea slowly changed into the halting action at Coral Sea before the decisive clash at Midway. As summer drew to a close, the crew of Ralph Talbot found themselves in harm’s way once again.

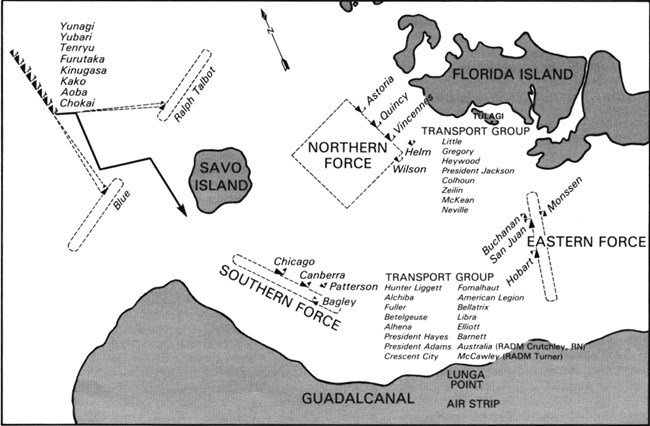

The 7th of August, 1942 saw the destroyer on the warm waters within the Solomon Islands, gathered with ships of the first amphibious landing in the Pacific. Codenamed Operation Watchtower, the strategy was to secure the islands of Guadalcanal and Tulagi.[10] As part of Destroyer Squadron Four, Ralph Talbot's helped to escort the transports which unloaded U.S. Marine and cargo onshore.[11] In the waters between the two landing sites, such a task proved difficult due to the number of passageways. To the west lay Savo Island, creating two paths into the sound which bore the same name. Another opening to the east gave any potential Japanese naval attack three ways to the transports. To safeguard all possible avenues, the warships that protected the landings split into three groups. Most of the Allied heavy cruisers available were placed into the groups around Savo.[12]

At Savo Island

With darkness bringing additional threats, the crew of Ralph Talbot received new assignments. In company with fellow destroyer USS Blue (DD-387), both ships were to steam out past Savo Island. The two destroyers acted as pickets against any approaching Japanese warships. It was determined that out of all the destroyers in Squadron Four, these two crews had the best results in using radar. Shortly before sunset on the 8th, the pickets headed out past Savo Island for their assigned stations. Blue steamed in a pattern west of the island, guarding the channel for the southern group of cruisers; Ralph Talbot headed north of the channel which was guarded by the northern group of cruisers.[13]

Photograph by Corp. L.M. Ashman, USMC. U.S. Marine Corps Photograph. Naval History and Heritage Command, USMC 61603.

Drawing is from U.S. Navy “All Hands” magazine from November 1980. Available from Wikipedia article on Battle of Savo Island.

Ever since the landings, the ship and its crew had been on constant alert, along with the rest of the fleet. Daylight had been marked with an air attack, compliments of the Japanese stronghold at Rabaul. The raid had been beaten off, though not without loss; a transport had to be abandoned, and fellow destroyer USS Jarvis (DD-393) was crippled by a torpedo.[14] Along with their fellow enlisted sailors, or bluejackets, Ralph Talbot's crew was exhausted after two days of being at action stations continuously.[15] With darkness shrouding the waters off Savo, the destroyer committed to its patrol. Humidity and rain filled the night with an oppressive nature, as the waters that time of year were a breeding ground for storms. With the burning USS George F. Eliot (AP-13) giving off the only light, the atmosphere appeared foreboding. An attack at night was a possibility but had been regarded as unlikely.[16]

The air was hot as Ralph Talbot steamed in a rectangular pattern through the simmering darkness. A quarter to midnight a tangible threat appeared. Not too far above flew a cruiser scouting plane, highly probably Japanese. The plane flew over Savo Island, aimed at larger Tulagi. Such an action did not go unnoticed as the destroyer sent off a message, "Warning, Warning. Plane over Savo heading east."[17]

Word spread over the short wave, voice radio between ships known as TBS, as well as the portable voice radio called TBO, which the Marines were using. While some of Ralph Talbot's squadron mates and cruisers received the call, there was difficulty in getting the warning up the chain of command.[18] Tensions were high as the crew entered Sunday, August 9. Minutes dragged out into hours while the ship steamed through the dark Pacific. Then, just before 2 AM, another warning filled the ship's airwaves. It was not fellow picket Blue, but destroyer USS Patterson (DD-392) near the southern cruiser group:

All ships! Warning! Warning! Three enemy ships inside Savo Island![19]

Alarm spread like wildfire as general quarters sounded. Crewmembers scrambled into position while Ralph Talbot picked up speed to 25 knots. In a few moments, the destroyer swung to the southwest in the direction of Savo. As Ralph Talbot steamed on, sailors topside noticed the glow of flares and starshells floating in the night sky. It was a mixture of enemy and friendly fire, as Japanese flares exposed the allied ships while Patterson's starshells struggled to mirror the action.[20] Ensign Louis Kelly later remarked that, from his position aboard Ralph Talbot, "Our ships were in complete light."[21]

In only a few moments, the glow melded with flashes of naval gunfire on the horizon. Though some confusion reigned on board, the crew saw a furious fight occur with the northern group led by heavy cruiser USS Vincennes (CA-44). Tracers flicked back and forth across the darkened sea. As those topside watched, one cruiser burst into flames from a hit while still returning fire.[22] Such visuals left no doubt that the American cruisers were being mauled. As Louis Kelly recalled, "They were taking a terrible licking because shell after shell hit and you could see the explosions."[23] As minutes ticked away, Ralph Talbot and its crew soon faced their own reckoning.

National Archives; Naval History and Heritage Command; 19-N-9957.

Fifteen minutes had not even passed the new hour when a bright glow illuminated Ralph Talbot. Unknown to the crew, the sole Japanese destroyer Yunagi accompanied the force of cruisers into battle. Though bathed in light for only a few seconds, the tin clad had been revealed to Yunagi's larger comrades. Just a few moments later, another searchlight caught Ralph Talbot in its ominous beam. This time however, the light was accompanied by the terrifying splash of shells landing close to the small destroyer. Up in the bridge, Lt. Commander Joseph Callahan for a moment thought the shooting was blue on blue. To the Pearl Harbor veteran, the colored dye with each splash and the direction suggested friendly fire. At once, flank (or top) speed was ordered as Ralph Talbot zigzagged to the west. Callahan also ordered the destroyer’s recognition lights flash while shouting a warning over the airwaves.[24]

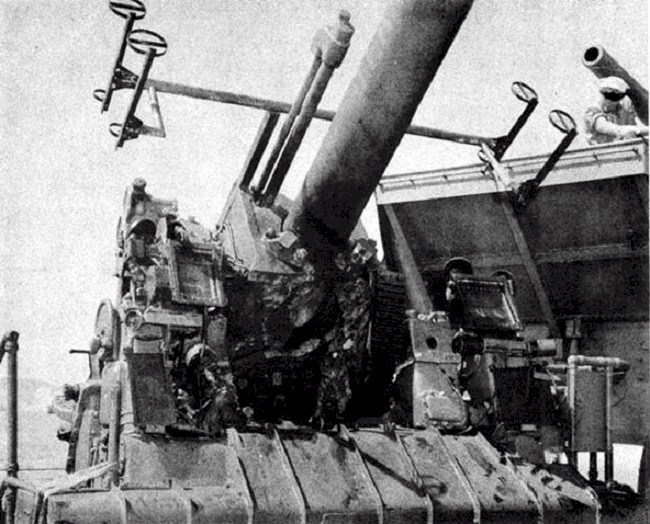

For a brief while, the moves seemed to work as firing ceased, though not before Ralph Talbot shuddered from a hit. Soon though, the form of an enemy cruiser revealed itself to the crew. Steaming into view was the ancient, yet capable, Yubari as it crossed the destroyer's stern. Shaded in the darkness was also fellow light cruiser Tenryu and heavier Furutaka, which had fired only minutes ago. All three ships opened fire at the sole destroyer while it maneuvered wildly amongst the splashes. Yubari's main battery drew the most blood as the cruiser’s salvos found their range. While Ralph Talbot swung to fire torpedoes and unmask its own guns, shell after shell slammed into it. First impact came in the chart house just below the bridge, followed by a second that destroyed the ship's radar and fire control equipment. Three more shells from Yubari hit the wardroom, the starboard torpedo tubes, and the Number Four gun on the stern.[25]

Photographer is G.J. Freret Jr. from Naval History and Heritage Command; NH 51876.

Naval History and Heritage Command; NH 48203.

It was over in moments. During that time Ralph Talbot fought back as best as it could. The crew returned fire with its main battery. Four torpedoes were also fired at Yubari, but the light cruiser evaded them during the exchange. Small fortune smiled on Ralph Talbot as the destroyer became enveloped in a rain squall. Firing died down around 2:30 AM as the elusive enemy ships slipped back into the night. In their wake lay confusion and devastation.[26]

After the Battle

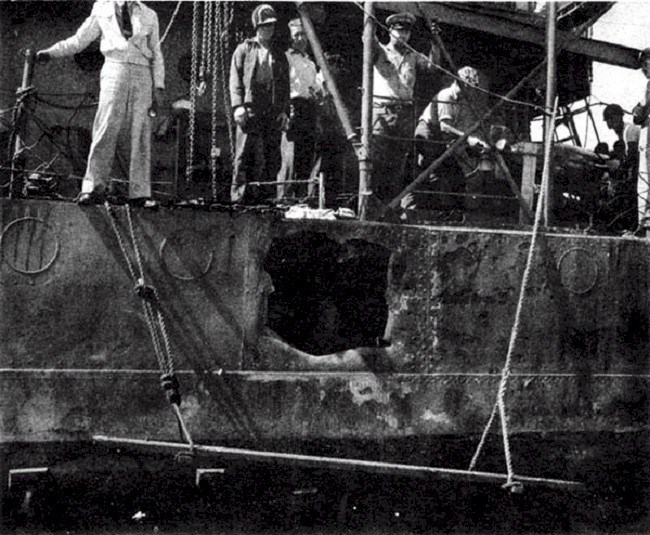

The damage aboard Ralph Talbot was great as the destroyer wallowed off Savo. Water poured in until the ship had lowered by 20 degrees on the starboard, or right, side. Main power had been knocked out, along with radio communications. Fires raged aboard and with no steam it seemed the destroyer was doomed. Worse still were the casualties. Twelve sailors had been killed before the guns fell silent, including the doctor. One of the lost had not even been part of the ship's company. Coxswain Walter Cobb from USS Mugford (DD-389) had been rescued by Ralph Talbot following an air attack where he had been blown overboard. During the night action, he helped man the Number Four gun, losing his life when the mount was struck. More fortunate was young Larry Trudeau, who had been injured by shrapnel before falling into the sea. The 22-year-old spent over nine hours by himself before being rescued by USS Hopkins (DMS-13). He became one of the 23 sailors wounded by battle’s end.[27]

Courtesy of the Navy Department Library, War Damage Report No. 51; Available from NavSource Naval History; Catalog Number: 0539031.

Battered and bloodied, Ralph Talbot was in danger of sinking. Indeed, some initially considered whether to abandon ship. To Ralph Talbot’s skipper, the decision was never in doubt. Having risen from engineering to command, Lt. Commander Joseph Callahan immediately directed the crew’s efforts to save the ship. With fire at sea being an incredible danger, all hands pitched in with bucket brigades until the blazes were smothered. Belowdecks, the crew repaired steam lines until the destroyer was able to limp into the shallow waters around Savo. Once there, the torpedo mounts were cut off and dumped over the side to lighten the weight. Damage control teams crafted a patch on deck using mattresses and timber. Carpenter's Mate Sharitt Baker helped place the patch over the hull.[28] For young Baker, the repair carried a heavy weight, for the hole was in his berthing compartment. The memory remained strong in his mind decades later as he reflected, "We lived down there…It is pretty hard to tell this story."[29]

Courtesy of the Navy Department Library, War Damage Report No. 51; Available from NavSource Naval History; Catalog Number: 0539032.

By dawn's light, Ralph Talbot had been repaired enough to steam on its own. Radio operators made contact with the rest of the fleet as the destroyer reached the anchorage off Guadalcanal. As darkness retreated, the true devastation of the battle was revealed. Though heavily damaged, Ralph Talbot was fortunate to have stayed afloat. In the blackness of the early morning, northern cruisers USS Quincy (CA-39) and Vincennes had sunk with heavy loss of life. Fellow USS Astoria (CA-34) lingered until noon when it, too, went down. In the southern group, cruiser USS Chicago (CA-29) wallowed from a torpedo hit. Australian HMAS Canberra (D33) had survived, but was forced to be purposefully sunk, or scuttled, in the morning.[30]

National Archives, Naval History and Heritage Command, 80-G-K-563.

Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 50346.

A much darker fate lay for Ralph Talbot's squadron mate Jarvis. Severely wounded on August 8, the destroyer had steamed out past Savo just before the battle commenced, where it disappeared. Only postwar inquiries revealed the tragic ending. Confusion and miscommunication ensured that the damaged ship, bound for Sydney, sailed out alone into the Pacific. As the Allies licked their wounds on the 9th, Jarvis was over 100 miles southwest of Guadalcanal when it was attacked by Japanese bombers. Slow, trailing oil, and with few guns, the ship's fate was sealed. With its radio already gone, life rafts jettisoned the day prior for weight, all hands onboard were taken by the sea. Only those wounded who had been transferred off the ship at Guadalcanal before the voyage survived, out of a complement of 240.[31]

In the coming weeks, US Navy analysis revealed many shortcomings in what became known as the Battle of Savo Island. Warning signs had been missed, and only the Patterson's words and gunfire gave a true alarm. For their parts, Blue and Ralph Talbot did not detect the incoming Japanese ships as they slipped past the picket line. Radar, while an essential tool, still had limitations around land masses, which became apparent after that August night. Both destroyers did not coordinate their patrols either, allowing an exploitable gap to form. Savo Island proved that the Japanese Navy, though reeling from Midway, was still a deadly foe. The cost was high; over 1,000 sailors lost their lives aboard the cruisers, even more with Jarvis’s toll added.[32]

For now, the campaign was over for Ralph Talbot as it steamed back to the West Coast for California. Bloodied, both ship and crew spent several months recovering from battle. Though mistakes had been made, both officers and enlisted men had faced the enemy and survived. Lessons had been learned and, as the war progressed, this Boston built destroyer and its sailors once more faced the storm of war.

They were down, but not out.

National Archives, Naval History and Heritage Command, 19-N-36580.

Footnotes

[1] "Start Work on Two New Destroyers at Navy Yard," The Boston Globe, October 28, 1935, 11 https://www.newspapers.com/.

[2] "To Name Destroyers Mugford and Talbot: Revolutionary Captain and Weymouth Flyer Honored," Daily Boston Globe, October 24, 1935, 36, Proquest Historical Newspapers; "Start Work on Two New Destroyers at Navy Yard," The Boston Globe, October 28, 1935, 11; "Navy Day Crowds see Warships' Keels Laid: Decoration of Byrd's, Aid Follows Start of Work on Destroyers Talbot and Mugford," Daily Boston Globe, October 29, 1935, 6 Proquest Historical Newspapers.

[3] "Destroyer to Be Named After Young War Flier," New York Times, January 16, 1936, 44, Proquest Historical Newspapers.

[4] "Relatives of Hero, Residents of Weymouth, Quincy Guests on Destroyer Ralph Talbot," Daily Boston Globe, July 17, 1938, B12, Proquest Historical Newspapers.

[5] "Dead Flyer’s Chum to Aid in Launching: U.S.S. Talbot Will Honor South Weymouth Man," Daily Boston Globe, October 30, 1936, 16, Proquest Historical Newspapers.

[6] Antony Beevor, The Second World War (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2012), 1-2; "Walsh Warns of War: Senator Speaks as Two Destroyers Are Launched at Charlestown," New York Times, November 1, 1936, F11, Proquest Historical Newspapers.

[7] "Walsh Warns of War," New York Times, F11.

[8] John D. Alden, Flush Decks & Four Pipes (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1965), 3; "Ralph Talbot (DD-390) 1937-1948," Naval History and Heritage Command, last updated June 1, 2016, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/r/ralph-talbot.html; "Classes of Destroyers," Official Website of the United States Navy, accessed July 16, 2020.

[9] "USS Ralph Talbot, Report of Pearl Harbor Attack," Naval History and Heritage Command, published February 21, 2018, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/archives/digital-exhibits-highlights/action-reports/wwii-pearl-harbor-attack/ships-m-r/uss-ralph-talbot-dd-390-action-report.html.

[10] Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle (New York, Random House, 1990), 50-53.

[11] Bruce Loxton and Chris Coulthard-Clark, The Shame of Savo: Anatomy of a Naval Disaster (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1994), 62.

[12] Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal, 98.

[13] Bruce Loxton and Chris Coulthard-Clark, The Shame of Savo, 81; Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal, 99; U.S. Navy, Combat Narratives: The Battles of Savo Island 9 August 1942 and the Eastern Solomons 23-25 August 1942 (Washington Navy Yard, D.C.: Naval History and Heritage Command, 2017), 2.

[14] James Hornfischer, Neptune's Inferno, 46-48.

[15] Colonel Thomas McCool, "Battle of Savo Island-Lessons Learned and Future Implications," 13; U.S. Navy, Combat Narratives, 35; Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, s.v. “bluejacket,” accessed October 3, 2020, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/bluejacket.

[16] Richard W. Bates and Walter D. Innis, The Battle of Savo Island: August 9th, 1942 Strategical and Tactical Analysis (Washington, D.C.: Department of Analysis, Naval War College, 1950), 4; Richard F. Newcomb, The Battle of Savo Island (New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 1961), 92-93.

[17] Richard W. Bates and Walter D. Innis, The Battle of Savo Island, 90; U.S. Navy, Combat Narratives, 3.

[18] U.S. Navy, Combat Narratives, 4.

[19] Richard W. Bates and Walter D. Innis, The Battle of Savo Island, 137; U.S. Navy, Combat Narratives, 9.

[20] Richard W. Bates and Walter D. Innis, The Battle of Savo Island, 136-137, 211, 257; Bruce Loxton and Chris Coulthard-Clark, The Shame of Savo, 207.

[21] "Marines, sailors recall Guadalcanal fighting," Doylestown Intelligencer, August 9, 1982, C2, Newspaper Archive.

[22] Richard W. Bates and Walter D. Innis, The Battle of Savo Island, 211.

[23] "Marines, sailors recall Guadalcanal fighting," Doylestown Intelligencer, C2.

[24] Richard W. Bates and Walter D. Innis, The Battle of Savo Island, 226, 227,257; "Two Coronadans remember Pearl Harbor," Coronado Eagle And Journal, December 7, 1972, 7, Newspaper Archive; Richard F. Newcomb, The Battle of Savo Island, 175.

[25] Richard W. Bates and Walter D. Innis, The Battle of Savo Island, 226-227, 257-259; Paul S. Dull, A Battle History of The Imperial Japanese Navy 1941-1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1978), 194; Bruce Loxton and Chris Coulthard-Clark, The Shame of Savo, 236.

[26] Richard W. Bates and Walter D. Innis, The Battle of Savo Island, 258-259, 264-265, 299; Bruce Loxton and Chris Coulthard-Clark, The Shame of Savo, 236; Richard F. Newcomb, The Battle of Savo Island, 176.

[27] Richard W. Bates and Walter D. Innis, The Battle of Savo Island, 300-301; "Survivors," The Billings Gazette, December 6, 2003, 3, Newspapers.com; "Walter B. Cobb," Naval History and Heritage Command, published November 17, 2015, Walter B. Cobb; Richard F. Newcomb, The Battle of Savo Island, 176, 194-195.

[28] Jeff Barlow, "Joseph W. Callahan and Ralph Talbot (DD-390)," Naval History and Heritage Command, published July 15, 2020, https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/world-war-ii-profiles/callahan-and-ralph-talbot.html; Richard W. Bates and Walter D. Innis, The Battle of Savo Island, 300; "Memories still vivid for veteran," The Garden City Telegram, December 7, 2016, 6, Newspaper Archive; Richard F. Newcomb, The Battle of Savo Island, 194-196.

[29] "Memories still vivid for veteran," The Garden City Telegram, 6.

[30] Richard W. Bates and Walter D. Innis, The Battle of Savo Island, 301; Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal, 113-114, 118-119; Bruce Loxton and Chris Coulthard-Clark, The Shame of Savo, 249.

[31] Richard W. Bates and Walter D. Innis, The Battle of Savo Island, 278; Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal, 120-121; Bruce Luxton and Chris Coulthard-Clark, The Shame of Savo, 118, 250-251.

[32] Richard W. Bates and Walter D. Innis, The Battle of Savo Island, 350; Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal, 99, 121.

Bibliography

- Alden, John D. Flush Decks & Four Pipes. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1965.

- Barlow, Jeff. "Lieutenant Commander Joseph W. Callahan and Ralph Talbot." Published October 15th, 2019. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/world-war-ii-profiles/callahan-and-ralph-talbot.html.

- Bates, Richard W., and Walter D. Innis. "The Battle of Savo Island: August 9th, 1942, Strategical and Tactical Analysis." Washington, D.C.: Department of Analysis, Naval War College, 1950.

- Beevor, Antony. The Second World War. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2012.

- "Two Coronadans remember Pearl Habor." Coronado Eagle and Journal, December 7, 1972. Found through Newspaper Archive.

- "Navy Day Crowds see Warships' Keels Laid: Decoration of Byrd's, Aid Follows Start of Work on Destroyers Talbot and Mugford." Daily Boston Globe, October 29, 1935. Found through ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Dead Flyer's Chum To Aid In Launching: U.S.S. Talbot Will Honor South Weymouth Man." Daily Boston Globe, October 30, 1936. Found through ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Relatives of Hero, Residents of Weymouth, Quincy Guests on Destroyer Ralph Talbot." Daily Boston Globe, July 17, 1938. Found through ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Marines, sailors recall Guadalcanal fighting." Doylestown Intelligencer, August 9, 1982. Found through Newspaper Archive.

- Dull, Paul S. A Battle History of The Imperial Japanese Navy (1941-1945). Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1978.

- Frank, Richard B. Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House, 1990.

- Hornfischer, James D. Neptune's Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal. New York: Random House, 2011.

- Luxton, Bruce and Chris Coulthard-Clark. The Shame of Savo: Anatomy of a Naval Disaster. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1994.

- McCool, Colonel Thomas. "Battle of Savo Island- Lessons Learned and Future Implications." Carlisle Barracks, PA: U.S. Army War College, 2002.

- Merriam-Webster.com "Bluejacket." Accessed October 3, 2020. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/bluejacket.

- Naval History and Heritage Command. "Ralph Talbot (DD-390) 1937-1948." Last updated June 1, 2016. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/r/ralph-talbot.html.

- Naval History and Heritage Command. "USS Ralph Talbot, Report of Pearl Harbor Attack." Published February 21, 2018. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/archives/digitized-collections/action-reports/wwii-pearl-harbor-attack/ships-m-r/uss-ralph-talbot-dd-390-action-report.html

- Naval History and Heritage Command. "Walter B. Cobb." Published November 17, 2015. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/w/walter-b-cobb.html.

- Newcomb, Richard F. The Battle of Savo Island. New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 1961.

- "Destroyer to Be Named After Young War Flier." New York Times, January 16, 1936. Found through ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Walsh Warns of War: Senator Speaks as Two Destroyers Are Launched at Charlestown." New York Times, November 1, 1936. Found through ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Official Website of the United States Navy. "Classes of Destroyers." Accessed July 16, 2020. https://www.navy.mil/navydata/nav_legacy.asp?id=139

- UNSW Canberra. "The Battle of Savo Island." Published April 2, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ULoRbr2ASFk

- U.S. Navy. Combat Narratives: The Battles of Savo Island 9 August 1942 and the Eastern Solomons 23-25 August 1942. Washington Navy Yard, DC: Naval History and Heritage Command, 2017.

- "To Name Destroyers Mugford and Talbot: Revolutionary Captain and Weymouth Flyer Honored." The Boston Globe, October 24, 1935. Found through ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Start Work on Two New Destroyers at Navy Yard." The Boston Globe, October 28, 1935. Found through Newspapers.com.

- "Memories still vivid for veteran." The Garden City Telegram, December 16, 2016. Found through Newspaper Archive.