Last updated: January 8, 2025

Article

Urban Renewal and New Schools Arrive in Charlestown

This article is part of the series "Desegregation in the Cradle of Liberty." This series explores the Black struggle for equal education in Boston from 1787 to 1976, culminating with protests and violence experienced under forced busing in Boston in the 1970s.

In the mid-1900s, Boston officials embarked upon a series of Urban Renewal projects attempting to revive and transform what they considered "unsatisfactory" parts of the city. Both nationwide and locally, these efforts often included demolishing older neighborhoods to make way for newer housing complexes, commercial and public buildings, and public spaces. These projects dramatically affected long-term residents, displaced communities, and altered the physical landscape of the city.

In Boston, the first attempt at Urban Renewal happened in the West End, home to Jewish, Italian, and Irish communities, alongside many other Eastern European immigrants. After the destruction of the West End, communities began to prepare for when urban renewal would be leveraged against them. They hoped to negotiate to retain their community.

By the 1960s, city planners set their sights upon Charlestown, a largely White working-class Irish American neighborhood, steeped in Revolutionary War history and home to the Bunker Hill Monument.

Having seen the destruction of the West End and the displacement of thousands during an earlier Urban Renewal project in the City, Charlestown residents mobilized to save their neighborhood. They advocated for a series of demands, including maintaining their housing level and establishing new schools.[1]

Courtesy of the FayFoto Boston photographs at Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections

In 1960, the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) proposed tearing down a significant number of housing units in Charlestown as part of its Urban Renewal efforts. Charlestown residents quickly formed two community advocacy organizations to fight this plan: The Self-Help Organization of Charlestown (SHOC), which many saw as representing "regular" people, and the Federation of Charlestown Organizations, which represented businesses, churches, and unions.

These community groups mobilized and as a whole rejected the BRA's plan. This forced the BRA to work with the Federation on a second proposal.[2] SHOC successfully shot down this second proposal in 1963, forcing the BRA to come up with a third proposal in 1965. The third proposal took effect after years of contentious debate and community protest.[3] Though the final plan did not please everyone, Charlestown residents, through their fierce advocacy, had fought back against city officials and succeeded in getting some of their concerns addressed.

This new plan included the building of two new elementary schools, Bunker Hill Community College, a new fire station, shopping mall, parks, playgrounds, a new arterial street, and, most significantly, the relocation of the elevated train tracks that ran down Main Street. This third plan included only 10% of Charlestown’s housing stock being destroyed, displacing 2,000 residents and resettling all of them in the neighborhood. New housing included 700 units of public housing and 200 units of private housing. The compromise also provided low-interest loans for homeowners to renovate additional units.

According to Moe Gillen, an opponent of Urban Renewal:

We got two new elementary schools, we got a junior college, we were on our way to getting a high school, and our next objective was to get a new middle school, so that we’d be totally encased in our little cocoon of Charlestown and our kids could go from kindergarten to junior college and never leave the town.[4]

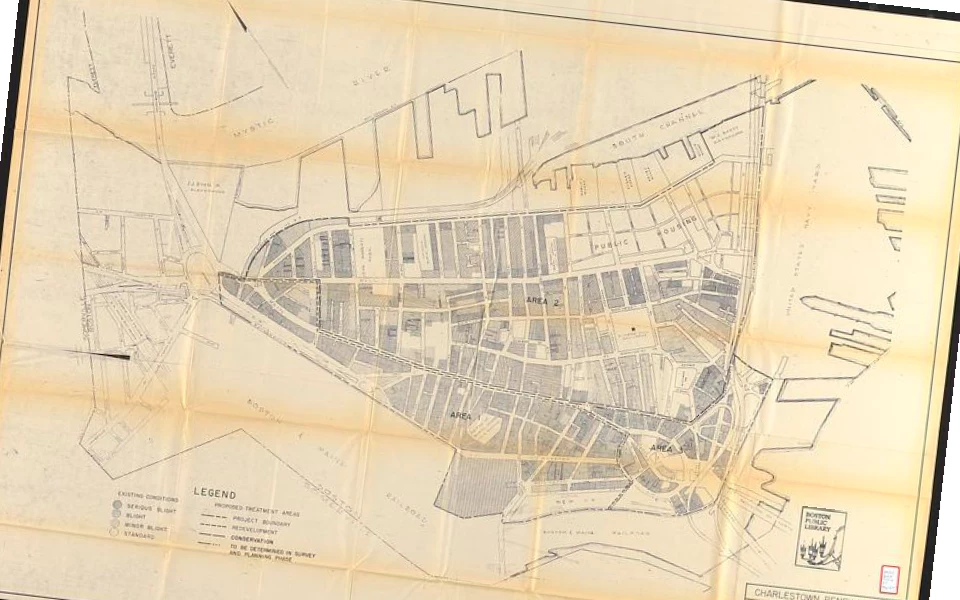

Left image

Charlestown Renewal Area Existing Conditions and Proposed Treatment Areas map from the Boston Redevelopment Authority

Credit: Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

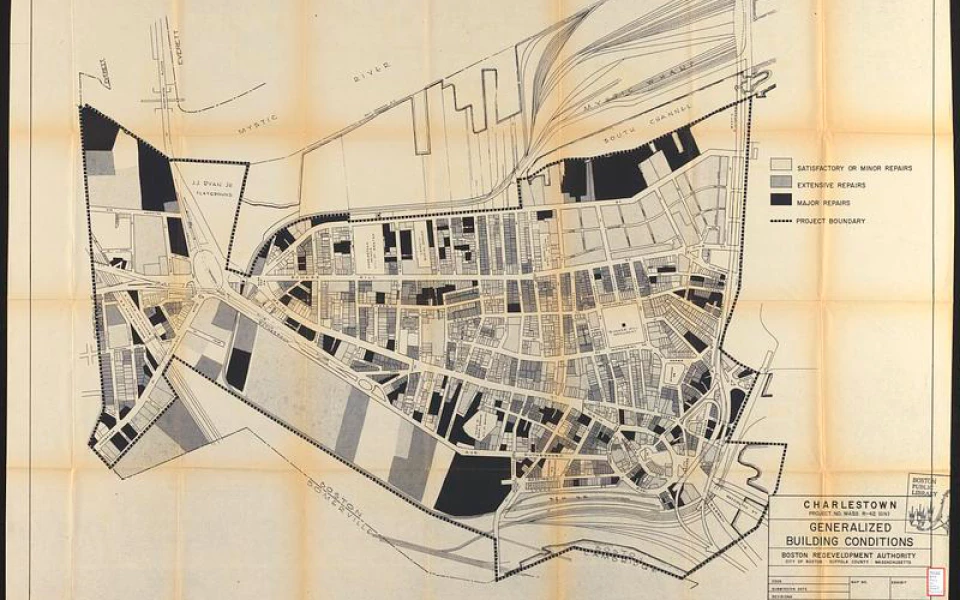

Right image

Charlestown Renewal Area Existing Conditions and Proposed Treatment Areas map from the Boston Redevelopment Authority

Credit: Leventhal Map Center at Boston Public Library

The efforts of Charlestown residents in their fight against Urban Renewal showed what positive community engagement and organizing could look like, and what it could achieve.

Less than a decade later, however, community organizing in the neighborhood took on a different tone. Many veterans of the fight against urban renewal helped lead the fight against the desegregation of the schools in 1975. This struggle became far more harrowing, combative, and, at times, took an overtly racist and violent tone as residents attempted to stop busing following the Morgan v. Hennigan case of 1974.

Overview Timeline Article

Black Struggle for Equal EducationFootnotes

[1] Ronald P. Formisano, Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s, (University of North Carolina Press, 1991): 121.

[2] The BRA’s initial plan called for 60% of Charlestown’s housing to be demolished. The second plan called for 20% of housing to be demolished, rehabilitating the rest, and building 1,400 new units.

[3] Jim Vabrel, A People’s History of the New Boston, (University of Massachusetts Press, 2014), 20-22.

[4] Moe Gillen, Oral History Interview Suffolk University Moakley Library.