Part of a series of articles titled Park Paleontology News - Vol. 16, No. 1, Spring 2024.

Article

Uncovering the Fossil Resources of Fort Pulaski National Monument

Article by Kelly E. Cronin, Christy C. Visaggi, Kathlyn M. Smith, and Laura Seifert

for Park Paleontology Newsletter, Spring 2024

NPS photo.

Introduction

Fort Pulaski, located in the mouth of the Savannah River in Chatham County, Georgia, was originally constructed to protect the port of Savannah after the War of 1812; the thick masonry walls were considered unbreachable at the time of its construction during the first half of the 19th century. Confederate troops garrisoned Fort Pulaski during the Civil War, but the fort was recaptured in 1862 when U.S. troops attacked with rifled cannons—a new weapon capable of destroying the walls of the fort. Fort Pulaski National Monument (FOPU) was established in 1924 by Calvin Coolidge to preserve this important piece of military history. In addition to the fort itself, FOPU preserves acres of salt marshes on Cockspur Island and McQueens Island, and the geologic history preserved in the stratigraphy under the present-day surface of the island records millions of years of the marine, estuarine, and terrestrial environments of coastal Georgia.

Though not primarily known for its paleontological resources, FOPU is situated in a potentially fossil-rich geologic context. Components of the original fort were constructed from local shell material and fossils were recovered from cores and construction ditches on Cockspur Island. The Savannah River area is known among fossil hunters as a source for fossil shark teeth, including megalodon teeth (Otodus megalodon). Various marine invertebrate fossils and Pleistocene mammals have also been found from Neogene or Quaternary sediments on nearby islands, including some of the first giant ground sloth fossils described from North America (Mitchell, 1824). Previously, most fossils known from the region were found outside of park boundaries.

A reassessment of the paleontological resources at FOPU was solicited by park staff. Through a partnership between the NPS and the American Geoscience Institute, support was made available to undertake fossil surveys at the park. In 2023, three paleontologists (Figure 1) from Georgia State University and Georgia Southern University collaborated with the park and explored promising sites within and around FOPU to identify potential paleontological resources.

Cockspur Island Geology and Known Fossils

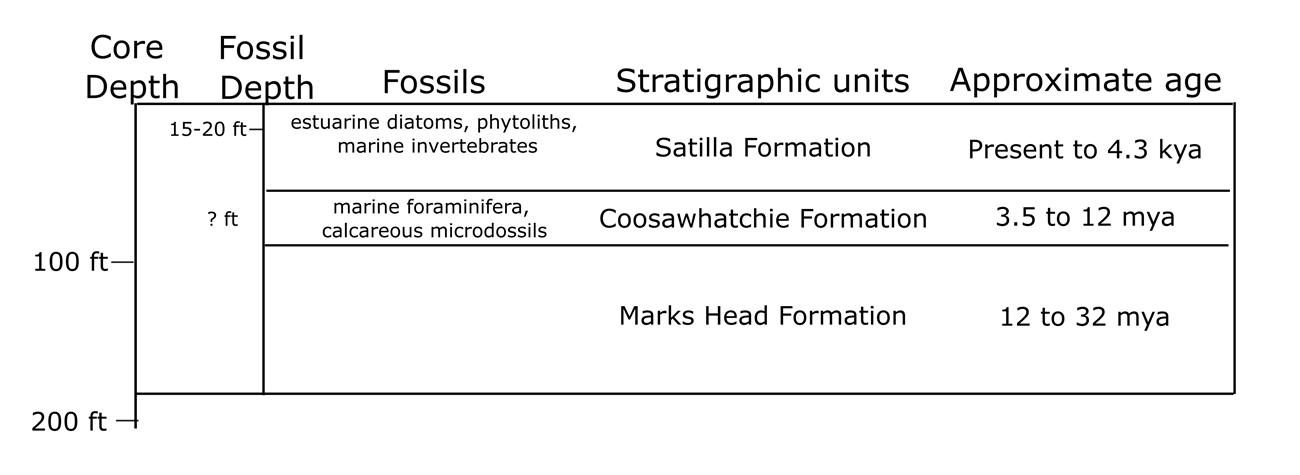

Prior data from a USGS core drilled on Cockspur Island in 2010 revealed sedimentary units ranging in age from 43 million years old to the present (Swezey et al., 2018). From the bottom to the top of the 1,017 foot core, the geologic units are: the Waverly Hill Formation, a glauconitic sand between 43 and 41 million years old; the Suwanee Limestone, a 780-foot-thick limestone between 41 and 32 million years old; the Marks Head Formation, a 94-foot thick unit of sand and mud ranging from 32 to 12 million years old; and the Coosawhatchie Formation, a 35-foot-thick unit consisting of sand and mud with phosphate ranging from 12 to 3.5 million years old. At the top is the Satilla Formation, a 53-foot-thick unit of sand and mud ranging in age from 4,300 years old to present. The Satilla Formation, including the Late Pleistocene-age Silver Bluff marine terrace and Quaternary terraces, comprises the surface sediments at Cockspur Island and unconformably overlies the Coosawhatchie Formation.

There are some known fossiliferous beds in the subsurface (Figure 2). A Georgia Geological Survey core dug at FOPU returned marine foraminifera (amoeba-like “shelled” single-celled organisms) and other microfossils from the Early Pliocene of the Coosawahatchie Formation (Weems and Edwards, 2001). Quaternary sediments excavated for construction of Fort Pulaski revealed a fossiliferous layer between 15 and 20 feet below the surface containing estuarine diatoms (microscopic algae with hard parts of silica), phytoliths (silica bits that grow in plant cells), and fragments of sponges and other marine invertebrates (Tweet et al., 2009).

Cenozoic mollusk shells, particularly oysters, can be found in high concentrations in several locations in FOPU. Parts of the fort itself were built using mortar made from lime, sand, and oyster shells. Oyster middens left by Native Americans near the Savannah River are the likely source for the lime and oyster fragments (Swezey et al., 2018).

Newly Discovered Fossils at Fort Pulaski

The paleontological resource inventory prioritized searching for fossils common to the surrounding area but not yet documented at FOPU, such as shark teeth and Pleistocene vertebrate bones. The effort was led by paleontologist Christy Visaggi, who was assisted by paleontologists Kelly Cronin and Katy Smith in coordination with park archeologist Laura Seifert and park staff Samantha Matera, Candice Smith, Dana McCammon, and Miguel Roman as supported by superintendent Melissa Memory. Several locations on Cockspur Island were explored. The most productive locality was found to be made up of dredge spoils that had been placed to protect the cultural resources associated with FOPU (Figure 3). This area is closed to the public primarily for safety reasons. Strong tides, currents and large wakes from cargo ships are common hazards. The beach closure has had the additional benefit of protecting roosting, feeding, and nesting sites of a variety of shorebird and migratory bird species, and may also help in maintaining fossil resources at this location. Examples of several new-to-FOPU marine and terrestrial vertebrate fossil taxa were found in this area.

NPS photo.

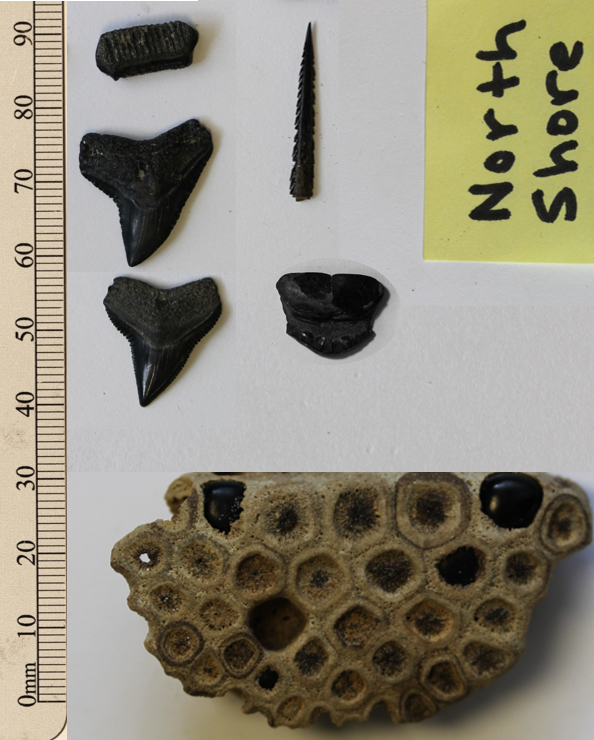

Marine fossils included a variety of shark teeth (Figure 4). Requiem sharks (genus Carcharhinus) and lemon sharks (genus Negaprion), which have fossil records that extend from the present to the Late Eocene; white sharks (genus Carcharodon), which have fossil records that extend from present-day great white sharks to at least the Middle Miocene; and ground sharks (genus Galeocerdo), which have fossil records that extend from present-day tiger sharks to the Middle Miocene were all present. Additional marine vertebrate remains uncovered during field surveys included ray dental plates and barbs, a tooth plate from a drum fish, and the mouth plate of a diodontid fish (Figure 4).

NPS photo.

Examples of terrestrial mammal fossils were also found, including several Pleistocene mammals. Equus (horse) cheek teeth (Figure 5) and a portion of proboscidean tusk dentin (probable American mastodon, Mammut americanum; Figure 6) were recovered. Multiple additional bone fragments were found, one of which may represent another probable Pleistocene megafauna but the identification has not yet been fully confirmed.

NPS photo.

The shark teeth and other vertebrate specimens cannot be definitively tied to specific stratigraphic formations, having been found loose as “float” specimens, not recovered in situ. Many of the identified taxa have long fossil histories that overlap the ages of the formations underlying FOPU and could also be from other Neogene or Quaternary units exposed nearby that are not necessarily recorded at FOPU. These fossils were likely deposited by storms or dredging to maintain the Savannah River harbor and shipping lane. Nevertheless, even though these fossils were no longer in their original geologic context, they have significance as new finds documented at FOPU and add to the understanding of Georgia fossils in the region.

NPS photo.

Conclusions

The fossils located through field efforts at FOPU in 2023 are likely only a preliminary sample of the paleontological resources that could be found in the future at the park. The Savannah River is dredged twice per year to maintain shipping infrastructure (Army Corps of Engineers), and each new dredge and strong storm could bring more fossils to the park. Furthermore, any periodic deepening of the channel could unearth new fossils that might end up at FOPU. Fossils could also be recovered if underlying strata were exposed on Cockspur Island as a result of any digging or construction that might disturb sediments containing fossils. Additional surveys and monitoring could be useful going forward to provide new insight on fossils that have yet to be discovered at the park. The fossils present opportunities to expand the focus of interpretive programming and resources into prehistory and paleontology and to further paleontological research at FOPU.

References

-

Mitchell, S. L. 1824. Observations on the teeth of the Megatherium recently discovered in the United States. Annals of the Lyceum of Natural History of New York, 1, 58-61.

-

Swezey, C.S., E. L. Seefelt, and M. Parker, 2018. A brief geological history of Cockspur Island at Fort Pulaski National Monument, Chatham County, Georgia: U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 2018‒3011, 4 p.

-

Tweet, J. S., V. L. Santucci, and J. P. Kenworthy 2009. Paleontological resource inventory and monitoring —Southeast Coast Network. Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRPC/NRTR— 2009/197. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

-

United States Army Corps of Engineers, n.d. Maintenance of Savannah Harbor

-

Weems, R.E., and L. E. Edwards, 2001. Geology of Oligocene, Miocene, and younger deposits in the coastal area of Georgia: Georgia Geologic Survey Bulletin 131, 124 p.

Related Links

-

Fort Pulaski National Monument (FOPU), Georgia—[FOPU Park Home] [FOPU npshistory.com]

Last updated: April 3, 2024