Part of a series of articles titled The Watsons Go to Birmingham—1963.

Article

Chapter 4: Froze-Up Southern Folks

Courtesy of LaBudde Special Collections, UMKC University Libraries.

Even after fifteen years in Michigan, Mrs. Watson is still afraid of Flint’s freezing cold winters.

She dresses Kenny and Joey in so many extra layers of clothing that the neighborhood kids call them “the Weird Watsons doing their Mummy imitations!” When the Watsons get to school, it’s Kenny’s job to help Joey out of her winter things. He carefully peels off the extra layers, and by the time Joey’s down to her school clothes, she is so sweaty that Kenny has to use a towel to dry her face and hair. To keep Joey from whining, Byron makes up a story about them being more capable of freezing because of Momma’s southern roots. The tale spooks Joey into not complaining about warmly dressing for the weather.

Thanks to Momma’s fear of the cold, the Watsons are the only kids at school with real rabbit fur-lined, leather gloves. For a while, Kenny shares his gloves with Rufus, and he eventually tricks Momma into giving him another pair so both he and Rufus can have a complete set. But soon, Kenny’s gloves go missing, and Larry Dunn mysteriously comes to school wearing them. He’s painted the gloves black in an attempt to disguise the stolen goods. Having leather gloves means Larry can better perform his “Maytag Washes,” i.e., rubbing snow in other kids’ faces so much that it looks like the spinning cycles of a washing machine.

When Byron finds out that Larry Dunn stole Kenny’s gloves, he and his friend Buphead get back at Larry by punching him and throwing him into the chain-link fence. Byron’s bullying increases, and he mocks Larry’s thin windbreaker and his hole-filled tennis shoes. Even though Kenny gets his gloves back, he feels sorry for Larry and wishes he had never told Byron what happened.

The Detroit News (MI), November 22, 1962, Z-6.

Fact Check: Were winter accessories expensive?

Kenny and his siblings are the only kids at Clark Elementary to have fur-lined leather gloves. Some of their classmates don’t have any gloves at all. How did families manage the cost of dressing children warmly?

What do we know?

Clothing has changed a lot since the 1960s. You might think first of the difference in style. But bigger changes include where and how clothing is made and sold, and how that impacted costs. Before the 1980s, most Americans wore clothing manufactured in the United States. It was more expensive than clothing is today, and people owned far less. Children's outfits were often passed on to a younger sibling or neighbor when they were outgrown. The fact that pants, shirts, and dresses were made to last contributed to this practice, as did the fact that people routinely cared for and repaired their clothing.

Fur-lined leather gloves like Kenny’s were available in department stores in the early 1960s. But children outgrow (and lose) winter accessories quickly, so few families purchased them for kids. Instead, many children wore hand-knitted mittens and gloves. During the years that the Watsons were in school, knitting was so popular in Flint that elementary schools offered classes for students. During the winter holidays, local organizations would also invite community members to knit mittens and hats to donate to Flint's youth.

What is the evidence?

Primary source: Penney's, "2 big days to save!," advertisement, The Detroit News (MI), November 22, 1962, Z-6.

The advertisement for a department store in nearby Detroit contains a listing for gloves in the middle row on the far right. It reads, "BOYS FUR LINED LEATHER GLOVES. Sizes 8 to 18. $2.44. Dressy cowhide gloves fully lined with warm fur. In black and brown. A long wearing wonderful gift."

To put things in perspective, $2.44 would equal $23.46 in 2022. Children’s leather fur-lined gloves were actually more affordable in Kenny’s day than they are today.

Primary source: Mamie Duncan, "Flint fashions," The Bronze Reporter (MI), March 2, 1963, 2.

In the 1960s, Flint's leading Black newspaper, The Bronze Reporter, published a weekly column by Mamie Duncan titled "Flint Fashions." It provided readers with sewing tips. The excerpt below is from a column published on March 2, 1963. Titled "Hint to Remember," it gives advice on how to make clothing last for multiple seasons:

"When making children’s clothes, be sure to add enough length to 'let down' for the next season—they have a way of growing out their clothes quickly! The tall slender youngster should have [?] clothes cut from a pattern comparable to the age of the youngster in question. Keep this in mind and you'll have well-dressed and delighted youngsters (oldsters, too!)"

Primary source: "Purl 33," The Flint Journal (MI), January 29, 1963, 17.

While mothers, aunts, and grandmothers often knitted gloves and other clothing for children, Flint's young people were eager to learn to knit as well. In fact, in the winter of 1963, Flint Public Schools struggled to keep up with the demand for knitting classes.

"There must be a run on yarn and knitting needles in the Flint area. A total of 33 knitting classes are opening this week in schools throughout the city. There originally were 17 set up for the Mott Program's winter term. Mrs. M. Eleanor Woolfe, consultant in arts and crafts for the extended-school-services department of the Flint Public Schools, said that first she added an assistant when the enrollment of a class exceeded 19. Next she split classes until the program expanded to 33 groups. Even some of these classes require assistants."

Secondary source: Shinobu Majima, "Clothing consumption," in Encyclopedia of Consumer Culture, ed. Dale Southerton (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2011). doi.org/10.4135/9781412994248.n70

"According to consumer expenditure data [from 1961-2001], clothes shifted from being durables (expensive items required by everyone and bought infrequently) to consumables (cheap items bought frequently as part of active engagement with consumption). This is indicated by the decline of percentage share of total household expenditure spent on clothing and by the rise of absolute amount of clothes purchased."

Fact Check: Was unsupervised play common in Kenny’s day?

Larry Dunn and Byron play rough, and no adults are there to intervene. How typical was this?

What do we know?

It was common for children to play together outdoors—both at school and in their neighborhoods—without parents and teachers supervising. While adults are almost always supervising school grounds today, in the 1960s, kids were often left to play on their own. In fact, parents and experts at the time believed that children’s independence was crucial for their development. Children regularly walked or rode their bikes to school unaccompanied by adults. Beginning in the 1970s, more and more adults worried about children getting hurt. They started planning more of children’s freetime activities, including their play. This trend has continued. Today, it is significantly less common than it was in the 1960s for American children to spend time outside unattended.

- Duration:

- 1 minute, 15 seconds

Examples of unsupervised play outdoors in the 1960s. Excerpted from "To Touch a Child", a 1962 public relations documentary film for the Mott Foundation, a private foundation established in 1926 by an industrialist affiliated with General Motor Company.

Primary source: John F. Schereachewsky, "School yard's jungle law: you and your child," The Hartford Courant (CT), June 16, 1963, 3E.

"Here is our set up. There are two recess periods totalling one hour's time. A teacher told me that at times there are 400-500 pupils playing in the yard with three teachers on duty. When I asked if she felt that was adequate supervision, she said, 'Well, no. We don't like the situation, either, but there is nothing we can do about it. You know, that's the only relaxation time we teachers get all day. When it is my turn in the yard I have to spend all my time trying to keep the disrespectful older children away from the younger ones.' One correspondent continues with her own words: 'No attempt is made to teach the children organized games. They are free to roam, make up their own games and rules, and otherwise express themselves freely, sometimes with a stick, a stone, a push, shove or kick.'"

Secondary source: Markella B. Rutherford, "Keeping tabs on kids: children's shrinking public autonomy," in Adult Supervision Required: Private Freedom and Public Constraints for Parents and Children (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2011): 60–88. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5hj9c9.7

One way "that children's decreased public autonomy [freedom] is evident is in changing descriptions of children's free time and neighborhood play. In popular advice texts throughout most of the twentieth century, it is apparent that school-age children roamed and played in neighborhoods without adults accompanying them. Teens and preteens were described riding bicycles, buses, and subways all over towns and cities. Kids were commonly sent on errands, such as going to a grocery store or post office, by themselves. Hitching rides around and between towns was apparently a common practice. Sometimes mobility was a source of conflict between parents and children when kids asked for rides from parents who believed that kids should be more independent in their mobility."

The Flint Journal (MI), April 1, 1963.

Fact Check: Were "Maytag Washes" a common form of bullying?

Larry Dunn invents a cruel game that involves rubbing snow in kids' faces. Inspired by the popular brand of washing machine, he calls this "Maytag Washes." Is his use of a company brand to name his playground game historically accurate?

What do we know?

Following World War II, a boom in advertising helped make Americans more brand conscious. Teenagers and children like Larry, Byron, and Kenny would have learned the names of products through television commercials, popular magazines, and everyday conversations. Television was particularly influential, as scheduled children's programming was regularly interrupted by advertisements for toys, clothing, food, and other items marketed for youth. It is likely that Larry and other children heard their parents referring to new appliances by their brand name like Maytag. Knowledge of brand names was often associated with a family's class status and communicated people's desire for products and technologies that promised a comfortable lifestyle.

Where is the evidence?

Primary source: "Buy Maytag at Greenley's," advertisement, The Flint Journal (MI), April 1, 1963.

Primary source: "Hoovermatic," television commercial, c. 1960-1969, Clio Awards Collection, Indiana University Libraries Moving Image Archive, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN.

- Duration:

- 1 minute, 5 seconds

"Hoovermatic," television commercial, c. 1960-1969, Clio Awards Collection, Indiana University Libraries Moving Image Archive, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN.

Voices from the Field

Post World War II Advertising Aimed At African American Consumers by Robert E. Weems Jr., the Willard W. Garvey Distinguished Professor of Business History at Wichita State University and author of Desegregating the Dollar: African American Consumerism in the Twentieth Century.

Play in Post-World War II America by Steven Mintz, Professor of History at UT Austin and author of Huck’s Raft: A History of American Childhood.

Photos & Multimedia

Courtesy of Richland Library, Columbia, S.C.

Alabama Department of Archives and History

City of Portland (OR) Archives, A2010-003.4276.

[MNCR_0061_0789_007] Seven Settlement Houses-Database of Photos (University of Illinois at Chicago), University of Illinois at Chicago. Library. Special Collections and University Archives.

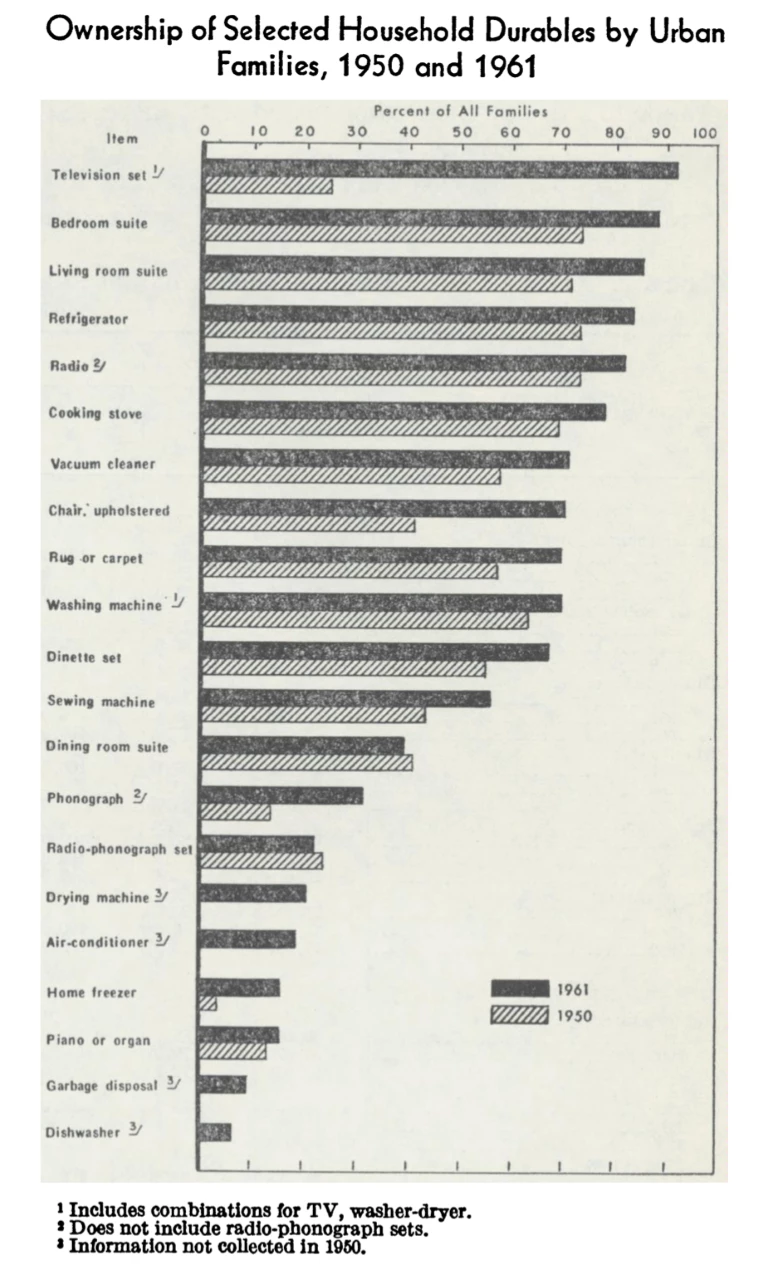

Thomas R. Tibbets, "Expanding Ownership of Household Equipment Monthly Labor Review," Monthly Labor Review 87, no. 10 (1964): 1133.

Writing Prompts

Opinion

Byron extracted revenge on Larry Dunn. Think about what it means to be “revengeful” (pay someone back) in response to a harm done. Create an organizational structure where you present the pros and cons for why revenge is or is not a good thing. Provide a concluding statement related to the two points of view presented.

Informative/explanatory

It is possible to freeze to death. Research the topic “hypothermia” and share what you have learned. Develop the topic with facts, concrete details, examples, and other information related to the topic.

Narrative

Byron made up a tall tale when he told Joey the garbage truck story. Choose a traditional “Tall Tale” and then orally tell the story to another person using your own words. Include dialogue and descriptions to manage the sequence of events.

Note: Wording in italics is from the Common Core Writing Standards, Grade 5. Sometimes paraphrased.

Last updated: December 28, 2023