Part of a series of articles titled The Power of Water.

Article

The Power of Water: Transportation

NPS Photo / C&O Canal NHP

Transportation

By Raisa Barrera

In this article you'll learn about a key function of the Chesapeake & Ohio (C&O) Canal during its peak operation: transportation. It was used largely to transport goods up, all the way near West Virginia and Western Maryland, all the way down to the former port city of Georgetown, Washington, DC, bordering of Virginia.

To better understand the desire for the Canal’s construction, this article will answer the following questions:

- Why the "Chesapeake & Ohio" for this canal?

- What is a canal?

- How does a canal lock work?

You will also find help resources, links, and a references section for your own investigative research. Explore and learn how water had the power to transform transportation in late 1800s.

Why the "Chesapeake and Ohio" for this canal?

Following the War of 1812, the rising prices of agricultural commodities drew settlers westward to find more fertile land and to become farmers. Farmers used the river system of the West, shipping wheat and corn down the Ohio River to the Mississippi and then further down the Mississippi to various ports where it was sold or shipped to other distant ports.

Transportation improvement along the Potomac River was highly desired as it was the only river on the East Coast that crossed the Appalachian mountain barrier and was considered the best route for Western trade. A land and trading venture organized by prominent Englishmen and Virginians, the Ohio Company of Virginia, established trails and wagon roads throughout the upper Potomac River Valley, as early as 1749.

These trails and wagon roads linked the Potomac River Valley with the Monongahela River, an Ohio River tributary, and access to the highly desired area known as the “Bread Basket of America” today. Connecting waters of the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries to the Ohio River was key to accessing those agricultural commodities out West.

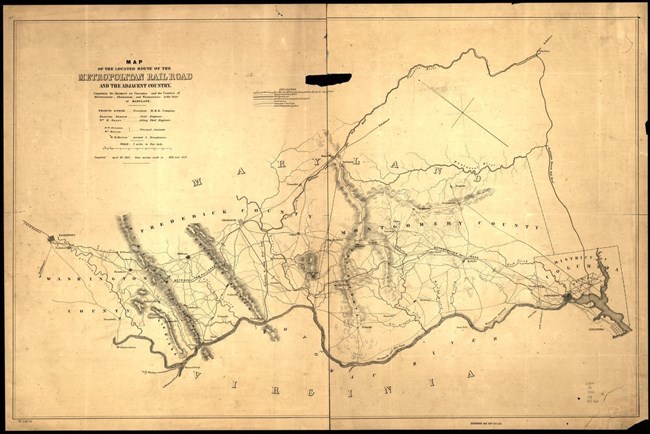

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

Map

Click map to enlarge. You'll see the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal outlined in a bolded line towards the bottom of the map.

Map of the located route of the Metropolitan Rail Road (MRR) comprising the District of Columbia, Montgomery, Frederick, and Washington Counties in Maryland.

This map was commissioned and created by Francis Dodge, MRR Company President, Edmund French, chief engineer, and W. R. Hutton, draughtsman, in April 30, 1855, from surveys made in 1853 and 1854.

What is a canal?

A channel is cut into the land with water flowing through which makes up the foundation of the canal. A canal is a man-made waterway built to transport goods and people from one place to another by water. Thanks to the efforts of many people, the C&O Canal was built alongside the Potomac River to allow boats to navigate through difficult terrain.

In 1772, George Washington founded the Potomac Company to build skirting canals through Virginia and Maryland to bypass the Potomac River’s five worst obstacles to transportation—the most serious being Great Falls. After George Washington become a national hero in 1784, he finally gained support from both Virginia and Maryland to build skirting canals, locks, and channels on the Potomac River.

Unfortunately, George Washington passed away in 1799 and was not able to see his dream project to its completion, however, by the 1820s, a proposal was made to build a permanent man-made canal along the river from Washington, DC, all the way to the Ohio River. Rights of the old Potomac Company were transferred to a new company incorporated by Virginia and Maryland and the “Great National Project” begun.

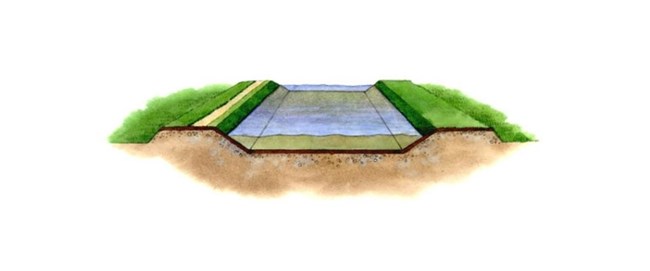

NPS Photo / Harpers Ferry Center

Canal Prism

Illustration shows a cutaway of the bed (or channel) of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal called the "prism" because the top was wider than the bottom.

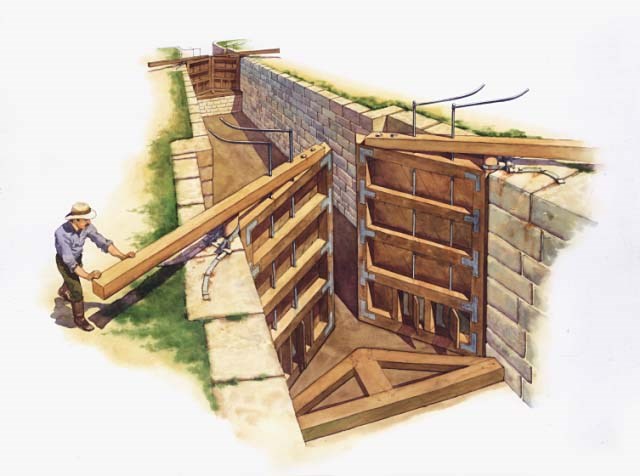

NPS Photo / Harpers Ferry Center

How does the canal work?

A lock is a device for raising and lowering boats between stretches of water of different levels on river and canal waterways. The distinguishing feature of a lock is a fixed chamber whose water level can be varied.

Locks have three elements:

- A watertight chamber connecting the upper and lower canals, and large enough to enclose one or more boats and the chamber’s water level can vary.

- Two gate doors at either end of the chamber. The two doors of the gate are opened to allow a boat to enter or leave the chamber; when closed, the gate is watertight.

- A valve that allows water both in and out of the chamber.

Moving Upsteam

To move upstream, a boat enters the lock through the lower gate and the gate doors are closed. The boat now sits in the bottom of the lock chamber and will need to rise eight feet to become even with the lock walls and the water level upstream.

Each gate door has two small paddles at the bottom. These paddles are connected to metal rods that run vertically up the height of the door. These rods stick out the top of the doors several feet. By using a lock key—which is essentially a giant wrench—a crew member can twist the metal rods and open the paddles.

Filling the Lock with Water

When it is time to fill the lock with water and raise the boat, the four paddles on the upstream gate are opened one at a time. A total of 90,000 gallons of water will rush in over several minutes. This will raise the surface of the water until it is level with the water upstream.

As the water comes and the chamber is filled, the boat will need to be stabilized to prevent the rushing water current from crashing it into the lock walls. This can be accomplished either by using the engine to steer the boat accordingly or by crew members using boat poles.

While there remains any difference in surface level between the water inside the lock chamber and the water upstream, the upper gate is impossible to open because of the accumulated pressure on the upstream side. As soon as the water levels, and therefore the water pressure, are equal on either side of the gates, the doors can open. The boat can then continue traveling upstream.

Moving Downstream

To move downstream, the process is reversed. The boat enters the lock with the chamber already filled with water. The gate doors are close behind the boat will be lowered eight feet to continue downstream. The four paddles of the downstream gate doors open, releasing 90,000 gallons of water out of the chamber and into the next level. The boat will again be stabilized in position as the water level decreases. Once the water levels and pressure are equalized on either side of the downstream gate, the doors will open and the boat can continue downstream.

NPS Photo

Locking Through

- The upper sluice valves are opened and water in lock is raised to level of upstream canal.

- Upper gates are opened and boat enters lock (top illustration). Upper gates and their sluice valves are closed.

- Sluice valves in lower gates are opened, allowing water to empty from the lock (middle illustration).

- The boat is lowered slowly as the water in the lock drops to level of downstream canal.

- Lower gate is opened and boat proceeds on lower level of canal (bottom illustration).

Library of Congress

Video from the Library of Congress: Down the old Potomac

Go back in time and view this 12 minute video showing scenes of the C&O Canal recorded in 1917. Read the summary below to get a preview.

"Follows a week-long, 180-mile trip on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal through the Potomac Valley from Cumberland, Md., to Washington, D.C. Includes scenes of the locks in operation; a mile-long, hand-dug tunnel which was built in 1840; coal barges plying the canal; Maryland farming country; Harper's Ferry; and Great Falls."

- Clark, J. G., & DeMark, J. B. (2019). Westward American Migration Begins. Salem Press Encyclopedia.

- Library of Congress. (n.d.). Today in History. Retrieved from Digital Collections: https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/october-10/#the-co-canal

- Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering & Technology. (2002). Leonardo's Miter Gate. Retrieved from https://civil.lindahall.org/mitergate.shtml

Last updated: July 30, 2021