Part of a series of articles titled Intermountain Park Science 2021.

Article

The Intersecting Crossroads of Paleontology and Archeology: When are Fossils Considered Artifacts?

- Vincent L. Santucci, Senior Paleontologist, Geologic Resources Division, National Park Service

- Don Weeks, Physical Resources Program Manager, Regional Office serving DOI Regions 6-8, National Park Service

- Rebeca Thornburg, Anthropology Program Intern, Regional Office serving DOI Regions 6-8, National Park Service

Introduction

The disciplines of paleontology and archeology are often viewed interchangeably by the public based in part on the fact that both disciplines study old objects preserved at or near the Earth’s surface. However, each field of study is distinct in terms of their scientific focus, academic training, and resource management practices.

-

Paleontology is the study of the history of life on Earth based upon fossils preserved within rock strata or some geologic context.

-

Archeology is the scientific study of historic or prehistoric (pre-European contact) peoples, their material cultures and activities through the recovery and analysis of artifacts, inscriptions, structures, and other such remains.

Despite the fundamental differences defining paleontology and archeology, the two fields of study share some common principles, methodologies and practices. The field collection or excavation of archeological and fossil sites often employ similar tools, techniques and technologies to support research and resource management. The standards employed by both paleontologists and archeologists are the basis for preservation of important scientific information that is associated with the fossils and archeological assemblages. The rigorous and systematic data collection during field excavations enables current and future scientists to analyze data that supports research and management of non-renewable resources.

Recent paleontological resource inventories undertaken within several National Park Service (NPS) parks known primarily for their significant archeological resources have revealed some important and overlapping relationships between fossils and artifacts. Understanding human knowledge and attitudes (human dimensions) towards paleontological resources through the co-occurrence of fossils and artifacts and/or tribal consultation (archeological context) helps us better appreciate those human values, perspectives, and beliefs. This understanding is important to the management, protection, and interpretation of these non-renewable resources. The consideration of both paleontology and archeology in resource management or interpretation, along with the respective practices of each discipline, contributes toward our understanding of how the past is interpreted, debated, and rejected or accepted (Santucci et al. 2016).

These human dimensions of paleontological resources or occurrences of fossils within an archeological context are represented by some interesting specimens documented during these fossil inventories (Table 1). Projectile points and stone tools manufactured from petrified wood are relatively common in a number of national parks located in the Four Corners area of the southwest U.S. More than 3,000 specimens of petrified wood modified by people into artifacts (e.g., projectile points, scrapers, hammer stones, flakes) are cataloged into the Interior Collections Management System (ICMS) for the various NPS areas (NPS, K. Beckwith, Registrar, Western Archeological and Conservation Center, personal communication, 2019). A few parks’ fossils have been fashioned into effigies, jewelry or other ornamental objects and have been recovered during archeological investigations in parks. Several examples of fossils incorporated into park prehistoric and historic structures are documented (Kenworthy and Santucci 2006; Santucci et al. 2020). Prehistoric trackways exhibiting co-occurrence between Late Pleistocene megafauna and humans have been recently confirmed at White Sands National Park, suggesting behaviors such as hunting (Bustos et al. 2018).

Outside of fossils used in the past for tools, ornamental objects, and building materials, there are underexplored relationships between people and fossils. These relationships include the spiritual connections, medicinal uses, and scientific understanding that extends beyond this discussion, but warrants acknowledgement for further conversation. For example, some American Indian Tribes have strong ties with fossils and hold information about fossils that western scientists might not fully understand. Through tribal consultation with American Indians, we can better understand and appreciate those relationships.

|

Park |

Fossil |

Modified (as described)/unmodified |

Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Aztec Ruins National Monument, New Mexico |

Shark Tooth |

Bead |

AZRU 448 |

|

Petrified Wood |

Biface |

AZRU 10358 |

|

|

Chipped stones (3) |

AZRU 1149, 11477, 11526 |

||

|

Core |

AZRU 6131 |

||

|

Flakes (2) |

AZRU 11441, 11452 |

||

|

Graver |

AZRU 5914 |

||

|

Hammer stone |

AZRU 11386 |

||

|

Knife blade |

AZRU 1698 |

||

|

Pendant |

AZRU 3023 |

||

|

Projectile point |

AZRU 10363 |

||

|

Scraper |

AZRU 5926 |

||

|

Shells |

Unmodified (3) |

AZRU 9854, 9855, 9862 |

|

|

Brachiopod |

Unmodified |

AZRU 2660 |

|

|

Crinoid Stem |

Unmodified |

AZRU 2023 |

|

|

Possible Leaf |

Unmodified |

AZRU 11252 |

|

|

Possible Seed |

Unmodified |

AZRU 10795 |

|

|

Bandelier National Monument, New Mexico |

Horn Coral |

Unmodified |

BAND 3424 |

|

Crinoid Stem |

Unmodified |

BAND 11008 |

|

| Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Arizona and Utah |

Ammonite |

Unmodified |

GLCA 7027 |

|

Bivalve or Brachiopod |

Unmodified |

GLCA 7034 |

|

|

Brachiopod |

Unmodified |

GLCA 19175 |

|

|

Navajo National Monument, Arizona |

Petrified Wood |

Broken hoe |

NAVA 7015 |

|

Drill |

NAVA 8003 |

||

|

Wood graver |

NAVA 8146 |

||

|

Hammer stone |

NAVA 8050 |

||

|

Flakes (6) |

NAVA 3554, 3575, 3579, 3586, 3592, 3601 |

||

|

Shells |

Unmodified (2) |

NAVA 1349, 2615 |

|

|

Crinoid Stem |

Unmodified |

NAVA 5610 |

|

| Walnut Canyon National Monument, Arizona | Petrified Wood |

Projectile points (7) |

WACA 2156 |

|

Other (7) |

WACA 984, 985, 992, 1000 |

||

| Snail |

Unmodified |

WACA 1372 |

|

| Bivalve |

Unmodified |

WACA 2218 |

|

| Brachiopods |

Unmodified |

WACA 1650 |

|

| Crinoid Stem |

Beads (7) |

WACA 1651 |

Definitions for some items in the table. Brachiopods are marine animals with shells on upper and lower surfaces. They have existed for 550 million years. Crinoids are marine animals with a mouth on the upper surface which is surrounded by feeding arms. They are an ancient fossil group with some surviving to the present day. Horn corals are an extinct order of corals. They grew in a long cone shape; the animal lived at the top of the cone.

Chaco Culture National Historical Park, New Mexico

Chaco Culture National Historical Park was established to protect hundreds of sites built by the Ancestral Puebloans. Chaco Culture preserves a record of human occupation from approximately 850 to 1150 A.D., and construction includes multi-story great houses with hundreds of rooms.

Courtesy of National Park Service, Chaco Canyon National Historical Park, CHCU 28466.

The park’s museum collection contains a large variety of fossils found within an archeological context. Human-modified petrified wood is well represented in the Chaco Culture NHP museum collection in the form of projectile points and other objects (Figure 1). Petrified wood is a fossil that forms by minerals replacing the original organic material of the plant; in other words, they are trees that have turned to stone. There are at least 8,500 records with petrified wood listed as one of the raw materials in the park collection (NPS, W. Bustard, Museum Curator, personal communication, 2019). Coal from the Cretaceous Menefee Formation was used by the people of Chaco in the production of beads and tools.

Some of these fossils were transported great distances such as from the Gulf of Mexico, Pacific Coast and Mexico (Tweet et al. 2009). The remains of the trace fossil Ophiomorpha (crustacean burrows) are present in the Cliff House Sandstone used as building material by Ancestral Puebloan people at Chaco Culture National Historical Park (Mytton and Schneider 1987).

Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado

Mesa Verde National Park was initially established on June 29, 1906 to protect archeological sites associated with the Ancestral Puebloan people, including extensive cliff dwellings. The Ancestral Puebloans lived in the area that is currently known as Mesa Verde NP for over 700 years, between 1,400 and 700 years ago. Over 5,000 archeological sites, including 600 cliff dwellings, are known from Mesa Verde National Park.

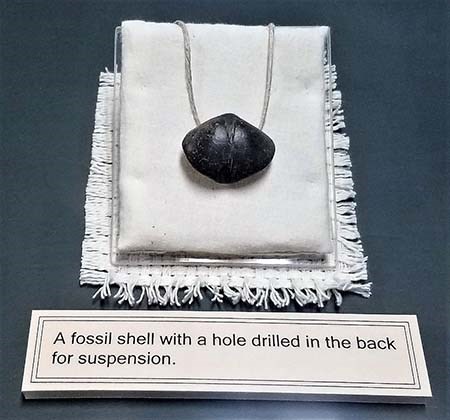

Courtesy of National Park Service, Mesa Verde National Park, MEVE 2109.

Mesa Verde National Park has a large collection of fossils that were found in an archeological context. The Ancestral Puebloans and other prehistoric groups in the Mesa Verde area demonstrated multiple uses for paleontological resources as a raw material for stone tools and other implements (Gerhardt 2003). Wood (1938) presented a brief study of types of stone used for tools and other artifacts at Mesa Verde National Park and referenced some fossils used in artifact production.

Currently, 139 Mesa Verde National Park catalog numbers have been assigned to petrified wood specimens associated with archeological collections. Those that have been tentatively identified to specific artifact types or human modifications include: awls (1), choppers (1), cylinders (1), disks (1), drills (4), flakes (11), gravers (1), grooved weights (1), hammer stones (3), knives (4), lithic cores (7), manos (1), medicine stones (4), polished stones (2), polishing stones (1), projectile points (3), scrapers (7), shaped or worked stones (2), spatulate objects (2), and tablets (4) (Tweet et al. 2009). In addition, a specimen of a fossil brachiopod with a drilled hole is on display at the Mesa Verde National Park museum (Figure 2).

Pecos National Historical Park, New Mexico

Pecos National Historical Park preserves cultural resources related to 12,000 years of human history. Among them are the remains of American Indian structures such as Pecos Pueblo, Spanish missions, Mexican-era homesteads, American frontier landmarks such as parts of the Santa Fe Trail (Santa Fe National Historic Trail), sites related to the Civil War battle of Glorieta Pass, and a 1900s ranch.

Courtesy of National Park Service, Pecos National Historical Park, PECO 21113, PECO 19000, and PECO 90, from left to right.

The historical park has an excellent record of fossils preserved in an archeological context. Alfred Vincent Kidder of the Robert S. Peabody Museum of Archaeology (Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts) collected a number of fossils from archeological sites within this area during work between 1915 and 1925, and these specimens are now in the collections of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology (Kidder 1932). According to Kidder, “many hundreds” of fossils were found at Pecos Pueblo during the excavations of 1915–1925. Most of them were marine fossils from “the limestone formations underlying the red sandstones of the valley”, which suggests their source is the Alamitos Formation. The marine fossils included corals, brachiopods, gastropods, and crinoids (Figure 3).

Courtesy of National Park Service, Pecos National Historical Park, PECO 11854.

Kidder also reported the discovery of a fossil rhinoceros tooth, remains of an extinct animal species that existed millions of years ago (Figure 4). Kidder noted that fossil specimens were sometimes found in refuse or rubbish mounds and suggested that they may have been collected as curios (Kidder 1932).

Courtesy of National Park Service, Pecos National Historical Park, PECO 1750.

Kidder observed that the specimens did not appear to be altered, although there are several fossil specimens worked into beads in the park museum collection (Figure 5). Some fossils specimens were contained within “medicine outfits” included with burials.

Petrified wood was found at Pecos NHP in ceremonial caches, showing little to no signs of modification, but sometimes exhibiting evidence of extensive handling. Kidder observed that the great majority of the wood was the brown or gray type found southwest of Santa Fe, which does not feature clear grain. He suggested that this wood was collected because of its unusual cleavage and the “clear, resonant tone which it gives when tapped.”

Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona

Petrified Forest National Park was originally proclaimed a national monument in 1906, and was later designated as a national park in 1962 to protect Late Triassic-age (approximately 200 million years ago) petrified wood resources that were in danger of being overexploited. The park’s mission and resources have since grown to include part of the Painted Desert, a shortgrass prairie, a variety of cultural and historic resources, and what is now known to be one of the best terrestrial Late Triassic fossil records in the world.

Courtesy of National Park Service, Petrified Forest National Park, PEFO 2568.

Petrified Forest National Park has long been known for the association of its fossils within archeological contexts. The petrified wood was part of the mythology of local tribes, including the Navajo, who saw the logs as the bones of the Great Giant Yietso, the monster who had been killed by their forefathers when they first arrived in the Southwest (the logs are called Yietso-bitsin), and the Paiute, who identified the logs as spent arrow shafts shot by the thunder god Shinauav (Ash 1972). Tools made from Petrified Forest National Park petrified wood are known throughout the Four Corners area. Projectile points made from Araucarioxylon arizonicum, an extinct conifer species, and other fossilized wood taxa have been found in the park (Kenworthy and Santucci 2006) (Figures 6 and 7).

Courtesy of National Park Service, Petrified Forest National Park, PEFO 245.

Evidence suggests that humans have a long history of utilizing petrified wood in the manufacture of points and tools. Petrified wood tools were being made as recently as the late 19th century in the Petrified Forest National Park area, when John Wesley Powell observed American Indians making axes and arrowheads (Mayor 2005).

There are also shells which are sourced from the Gulf of California at Flattop Village (Lubick 1996), raising the possibility of long-distance transport or trade of these fossils. A fossil bone pendant, a bone splinter awl, and fewer than six bone fragments have been discovered at a Flattops site (Wendorf 1950).

NPS photo.

Use of Petrified Forest National Park fossils is not restricted to small objects. Two structures at Petrified Forest National Park are known to have been constructed using petrified wood. Agate House Pueblo, the older structure, was built almost exclusively of petrified wood during the Pueblo II-III period (1050 – 1300 AD) and is probably not the only pueblo to have been built of this material (Figure 8). More recently, the Painted Desert Inn (originally the Stone Tree House) was built in 1924 using a great deal of petrified wood. Most of this petrified wood is now concealed beneath a stucco finish wall added by the Civilian Conservation Corps after the NPS acquired the inn in 1936 (Kenworthy and Santucci 2006).

Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument, New Mexico

Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument preserves notable examples of 17th-century Spanish Franciscan mission churches and convents as well as three large Pueblo Indian villages. The site was originally proclaimed as Gran Quivira National Monument on November 1, 1909 and renamed Salinas National Monument on December 19, 1980 when Abó State Monument and Quarai State Monument were incorporated with Gran Quivira National Monument, which in turn was later renamed Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument on October 29, 1988.

Humans have been present in the Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument area for thousands of years. Humans had reached the Estancia Basin by 12,000 to 10,000 years ago (McLemore 2000), and points from the Jay tradition (8,000 to 7,000 years ago) have been found at Quarai (Hurt 1990). Hurt (1990) described a number of artifacts from Quarai made of bone, shell, and chert and other potentially fossiliferous stones. The bone artifacts included awls, beads, leftover cut pieces, flageolets (flutes), handles, needles, possible scrapers, and decorated tubes, made from the bones of birds and deer and other mammals. Shell artifacts included beads, cut fragments, and pendants. There are at least three pieces of petrified wood listed in the Western Archeological and Conservation Center databases as collected from Gran Quivira. These include: a possible scraper; an unworked stone; and a group that includes possible petrified wood artifacts (Tweet et al. 2009; Thorpe et al. 2017).

Courtesy of National Park Service, Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument, SAPU 5119.

A number of Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument fossils have been carved into effigies or modified in some other way. The majority of these fossil finds were made in association with pueblo excavations of Mound 7 at Gran Quivira (Hayes et al. 1981). Most of the bird effigies are carved from fossil shells of bivalves and brachiopods (Figure 9). It is thought that they came from the local San Andres Limestone (Hayes et al. 1981), but sources for this conclusion are unclear and these fossils may have been brought here from many locations through travel and trade. Of the fossil shells stored at Western Archeological & Conservation Center, many have been modified in some way with straight grooves down the center of the shell and another straight groove on the ventral side almost perpendicular to the first.

From left to right, Courtesy of National Park Service, Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument, SAPU 5118 and SAPU 5438.

These shells are in various stages of modification with some having two or more grooves and some having barely one. Other shells in this collection show no signs of modification. Among the cultural fossil shells of brachiopods and bivalves, there are also culturally significant crinoids and corals. One particular rugose coral stored at Western Archeological & Conservation Center has been modified to look like a possible human or a tooth (Hayes et al. 1981; NPS, R. Fields, Archaeologist, personal communication, 2016).

Two brachiopods have also been located at Abó. It is likely that both of these brachiopods were brought to the area by humans (Thorpe et al. 2017) (Figure 10).

White Sands National Park, New Mexico

White Sands National Park was originally established as a national monument on January 18, 1933 in order to preserve the world’s largest gypsum sand dune field. The monument was redesignated as a park on December 20, 2019. The park lies at the northern end of the Chihuahuan Desert in the Tularosa Basin of south-central New Mexico.

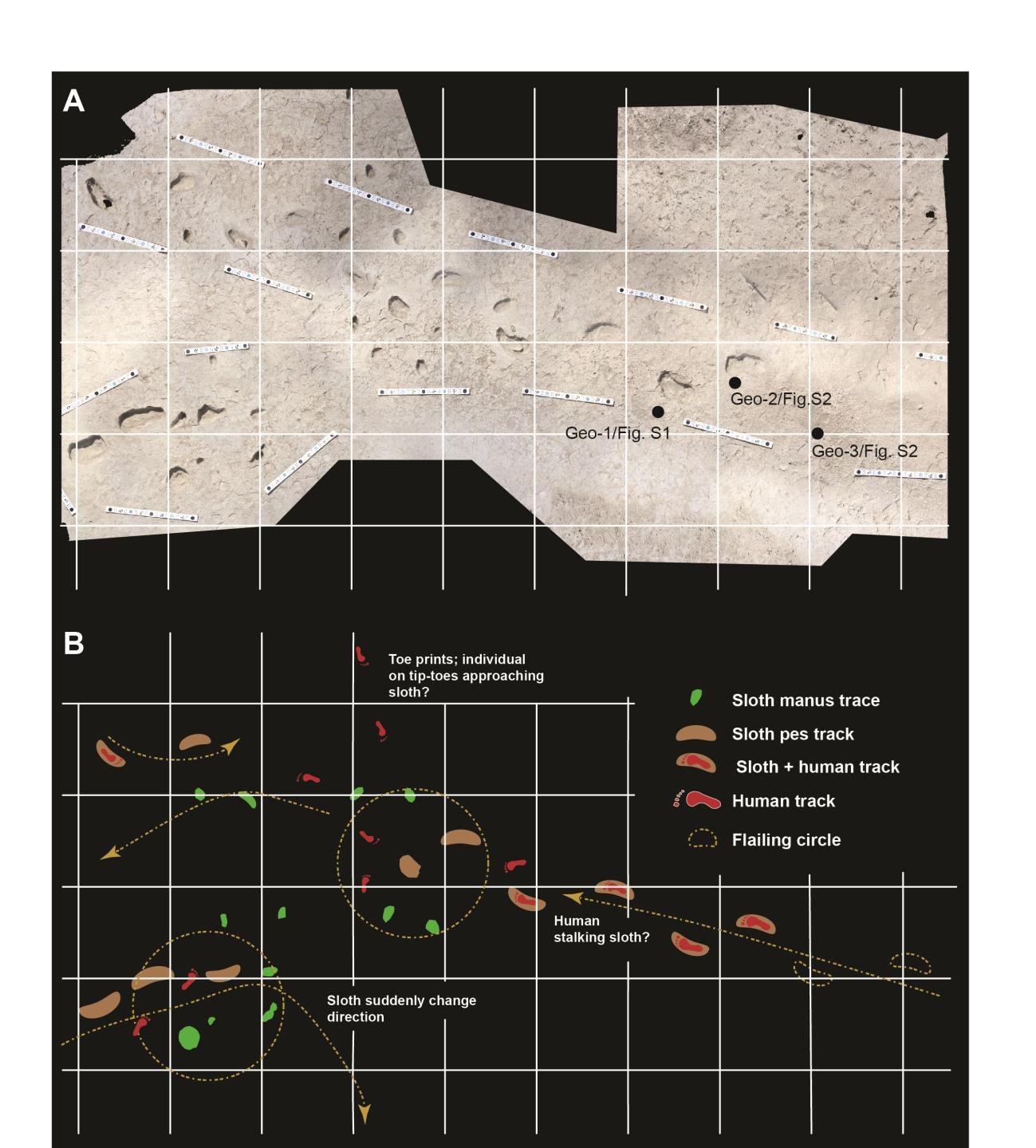

During the past decade, the NPS has investigated a late Pleistocene mega-tracksite within and surrounding White Sands National Park. A tracksite is an area where footprints and other trace fossils are preserved. A multi-disciplinary team of geologists, paleontologists and archeologists have been studying the White Sands National Park mega-tracksite for the past decade (Figure 11). The mega-tracksite consists of thousands of vertebrate ichnofossils (trace fossils) preserved in thinly bedded, gypsiferous playa lake sediments. The White Sands National Park mega-tracksite represents one of the largest concentrations of Pleistocene vertebrate tracks in North America. The trace fossil assemblage includes tracks of various late Pleistocene (Rancholabrean) megafauna such as proboscideans (mammoth), folivorans (ground sloth), canids (dire wolf), felids (saber-toothed cat), camelids (camel), and smaller artiodactyla (hoofed mammals). Hundreds of human footprints are also documented from the same late Pleistocene playa lake deposits preserving the Rancholabrean mammalian tracks. At least one locality preserves a contemporaneous co-occurrence of human and ground sloth trackways. Within the respective human and sloth trackways, there is repeated overprinting of sloth tracks by human prints, and conversely, human prints overprinted by sloth tracks (Bustos et al. 2018). This co-occurrence of human and sloth tracks at White Sands National Park is the first known interaction between humans and ground sloths documented in the fossil record. The fossil tracks at White Sands National Park represent one of the best examples of the intersecting crossroads of paleontology and archeology anywhere within the National Park System. Many new scientific findings associated with the late Pleistocene mega-tracksite are being documented at White Sands NP and will be presented in forthcoming scientific publications.

NPS photo.

Wupatki National Monument, Arizona

Wupatki National Monument was proclaimed on December 9, 1924 to protect ruins of red sandstone pueblos left by the Ancestral Puebloans. The monument is rich in archeological resources such as pueblos, pottery, and tools. Its main attraction is Wupatki Pueblo, a 100-room building that was the center of human activity in the area that is now known as Wupatki National Monument in the 1100s.

Wupatki National Monument has a number of specimens in the museum collection that represent human-modified fossils from an archeological context. One of the more interesting occurrences at the national monument is a fire hearth made of petrified wood. Several specimens were collected from within the Wupatki Pueblo including: a projectile point containing a possible fossil sponge; a petrified wood fragment modified into a bead; and a petrified wood scraper. Additional human-modified fossils were collected during archeological surveys of the Citadel Pueblo and Nalakihu Pueblo including: petrified wood projectile points; petrified wood biface; petrified wood flake; and a fossil coral.

NPS photo.

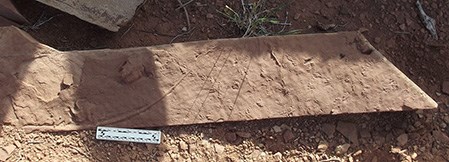

American Indian cultures in and around Wupatki National Monument used the geologic resources of a particular area to their advantage. In 1947, monument custodian David Jones reported on an interesting discovery he made just outside the boundary of the monument (on land administered by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation) while surveying the area with paleontologist Dr. Sam Welles and students from the University of California Museum of Paleontology (Jones 1947a, 1947b). The group encountered a historic dwelling, known as a hogan, which was constructed by Emmet Lee in the early years of the 20th century.

NPS photo.

Several blocks of Triassic Moenkopi Formation with prominent fossil vertebrate tracks were incorporated into and just outside the structure of the hogan (Figures 12 and 13). These tracks are so obviously visible in the slabs, it suggests that Lee was aware of the tracks and positioned them in and around the hogan to ensure their visibility.

Conclusion

This paper highlights 12 NPS areas and represents just a few examples of fossils which have been documented in an archeological context. Limited, but similar, resources are also known from Bryce Canyon National Park, Canyonlands National Park, Capitol Reef National Park, Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Chiricahua National Monument, El Malpais National Monument, El Morro National Monument, Fort Bowie National Historic Site, Grand Canyon National Park, Guadalupe Mountains National Park, Hohokam Pima National Monument, Hubbell Trading Post National Monument, Montezuma Castle National Monument, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Petrogylph National Monument, Tumacacori National Historical Park, Tuzigoot National Monument, Yucca House National Monument and Zion National Park. Additional research will likely yield additional NPS areas that preserve human-modified fossils and fossils that occur in an archeological resource context.

Five observations were derived from compiling data for this manuscript:

-

The prehistoric and historic utilization of petrified wood and other fossils in the manufacturing of stone tools and projectile points is well-documented from NPS units in the Four Corners region of the Colorado Plateau. Pre-Columbian Americans appear to have recognized the value of petrified wood as a raw material for the production of tools and weapons. Example: projectile points produced from petrified wood at Petrified Forest National Park.

-

Fossils found in an archeological context may provide information related to the procuring of fossils from great distances and long-distance transport of fossils by humans, pilgrimage and trade activities by prehistoric peoples. Example: fossil horn coral found at Bandelier National Monument.

-

Historic structures occasionally incorporate fossils within the geologic materials used in the construction of cultural features. These occurrences may be intentional or unintentional actions by those involved in the construction of the historic structures. Example: Agate House at Petrified Forest National Park.

-

Fossils hold some sacred, ceremonial or other spiritual values to prehistoric peoples and their descendants in the American Southwest based on the occurrence of some fossils contained in “medicine outfits” associated with human burials (funerary objects) and fossils found in ceremonial caches. Example: petrified wood in “medicine outfits” at Pecos National Historical Park.

-

The presence of fossils in archeological sites within national parks are important to American Indian tribes, and therefore, indicate the need for parks to consult with tribes concerning their disposition and interpretation.

Considering both paleontology and archeology in resource management or interpretation is a beneficial approach in order to better understand how a greater understanding (or knowledge) of the past is created, debated, and rejected or accepted (Santucci et al. 2016). Additional research involving the occurrence of human-modified fossils and paleontological resources of importance to tribes will contribute to our understanding of this interesting and important human dimension of fossils (Pueblo of San Felipe, P. Stout, Director of Department of Natural Resources, personal communication, 2019).

As suggested earlier, there is potential for more collaboration between paleontology, archeology, and cultural anthropology with American Indian populations. The National Congress of American Indians, Resolution #SD-15-020, To Protect Paleontological Resources on Tribal and Ancestral Tribal Lands states:

“…there are fossilized remains of animals and plants that were once on this earth, and respect for these remains are upheld by Indian people today because these fossilized remains are important cultural items having ongoing historical, traditional, and cultural importance for Indian people, tribes, and pueblos…” (National Congress of American Indians, 2015).

Adrienne Mayor (2007) addressed the exclusion of American Indian voices in paleontology. According to Mayor (2007), American Indian tribes should be allowed to aid in the interpretation of paleontological specimens, especially if those specimens were altered through human processes, causing them to become archeological artifacts. Mayor joins in the call that was put forward by Jason Kenworthy and Vincent Santucci (2006) to relate paleontological finds with ethnographic histories (documenting the traditions and sociopolitical practices among people) through tribal consultation. American Indians have always had a poorly explored tie with fossils, but yet they have a spiritual connection, they have used fossils for medicinal purposes, and they have scientific theories regarding fossils.

As part of the review process of this manuscript, the authors reached out to over 50 Tribes traditionally associated to the National Park units mentioned in this manuscript for review and comments. Those who responded were appreciative of elevating the connection between Native American tribes and paleontological resources. Pinu’u Stout (Director - Department of Natural Resources, Pueblo of San Felipe) stated that the manuscript was “well done and timely” and invited a deeper conversation of current efforts to protect paleontological remains on land adjacent to the San Felipe Pueblo.

Acknowledgments

There are a number of National Park Service employees who have provided valuable assistance with our research related to this publication. We would like to extend our appreciation to: Jim Kendrick, Kim Greenwood, and Rosemary Sucec (National Park Service Regional Office serving DOI Regions 6-8); Kim Beckwith and Tef Rodeffer (Western Archeological & Conservation Center); Wendy Bustard (Aztec Ruins National Monument and Chaco Culture National Historical Park); Gwenn Gallenstein and Lisa Leap (Flagstaff Area National Monuments); Brian Harmon and Lisa Riedel (Glen Canyon National Recreation Area); Jan Balsom, Colleen Hyde, and Kim Besom (Grand Canyon National Park); Tova Spector, Tara Travis, and Samuel Denman (Mesa Verde National Park); Matthew Smith (Petrified Forest National Park); Marc LeFrancois and Ron Fields (Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument); David Bustos (White Sands National Park); and Robyn Henderek and Miriam Watson (Zion National Park). We also extend our thanks to paleontologists Justin Tweet and Diana Boudreau for their review of this manuscript.

References

Ash, S. R. 1972.

The search for plant fossils in the Chinle Formation. Pages 45-58 in C. S. Breed and W. J. Breed, editors. Investigations in the Triassic Chinle Formation. Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin 47, Flagstaff, Arizona.

Bustos, D., J. Jakeway, T. M. Urban, V. T. Holliday, B. Fenertry, D. A. Raichlen, M. Budka, S. C. Reynolds, B. D. Allen, D. W. Love, V. L. Santucci, D. Odess, P. Willey, H. G. McDonald, and M. R. Bennett. 2018.

Footprints preserve terminal Pleistocene hunt? Human-sloth interactions in North America. Science Advances 4:1-6.

Gerhardt, K.M. 2003.

Flaked lithic material sources in southwestern Colorado. Abstracts with Programs – Geological Society of America 35(5):40–41.

Hayes, A.C. 1981.

Excavation of Mound 7, Gran Quivira National Monument, New Mexico. Publications in Archeology 16. National Park Service, Washington, D.C.

Hurt, W. R. 1990.

The 1939-1940 excavation project at Quarai Pueblo and Mission building, Salinas Pueblo National Monument. Professional Paper 29. National Park Service Southwest Cultural Resources Center, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Jones, D. J. 1947a.

Wupatki National Monument. National Park Service Unpublished Report, Southwestern Monuments February Report, Coolidge, Arizona.

Jones, D. J. 1947b.

Wupatki National Monument. National Park Service Unpublished Report, Southwestern Monuments July Report, Coolidge, Arizona.

Kenworthy, J. P., and V. L. Santucci. 2006.

A preliminary inventory of National Park Service paleontological resources in a cultural context: Part 1: A general overview. Pages 70-76 in S. G. Lucas, J. A. Spielmann, P. M. Hester, J. P. Kenworthy, and V. L. Santucci, editors. America’s Antiquities: 100 Years of Managing Fossils on Federal Lands. Proceedings of the 7th Federal Fossil Conference, New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin No. 34, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Kidder, A. V. 1932.

The artifacts of Pecos. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, 314 pp.

Kunz, G. F. 1886.

Agatized and jasperized wood of Arizona. Popular Science Monthly 28:362-367.

Lubick, G. M. 1996.

Petrified Forest National Park: a wilderness bound in time. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, Arizona.

Mayor, A. 2005.

Fossil legends of the first Americans. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Mayor, A. 2007.

Fossils in Native American lands whose bones, whose story? Fossil appropriations past and present. National History of Science Society annual meeting, November 1-2, 2007. Washington D.C.

McLemore, V. 2000.

Manzano Mountains State Park and Abo and Quarai units of the Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument. New Mexico Geology 22(4):108-112.

Mytton, J. W., and G. B. Schneider. 1987.

Interpretive geology of the Chaco area, northwestern New Mexico. Miscellaneous Investigations Series 1777. U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia.

National Congress of American Indians. 2015.

To Protect Paleontological Resources on Tribal and Ancestral Tribal Lands. The National Congress of American Indians Resolution #SD-15-020. Washington, D.C., 2 pp.

Santucci, V. L., P. Newman, and B. D. Taff. 2016.

Toward a conceptual framework for assessing the human dimensions of paleontological resources. Pages 239-248 in R. M. Sullivan and S. G. Lucas, editors, Fossil Record 5. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 74, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Santucci, B.A., C. Moneymaker, J.F. Lisco, and V.L. Santucci, 2020.

An overview of paleontological resources preserved within prehistoric and historic structures. Pages 347-356 in S. G. Lucas, A. P. Hunt, and A. J. Lichtig, editors, Fossil Record 7, New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 82, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Thorpe, E. D., V. L. Santucci, J. Tweet, and D. Weeks, 2017.

Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument: paleontological resources inventory. Natural Resource Report NPS/SAPU/NRR— 2017/1436. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Tweet, J.S., V.L. Santucci, J.P. Kenworthy, and A. L. Mims. 2009.

Paleontological resource inventory and monitoring—Southern Colorado Plateau Network. Natural Resource Technical Report. NPS/NRPC/NRTR—2009/245. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Wendorf, F. 1950.

The Flattop Site in the Petrified Forest National Monument. Plateau 22(3):43-51.

Wood, H.R. 1938.

Types of stone used for tools by the Mesa Verde Indians. Mesa Verde Notes 8(1):13–17.

Last updated: January 29, 2024