Last updated: August 14, 2023

Article

The Green Run

US DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY

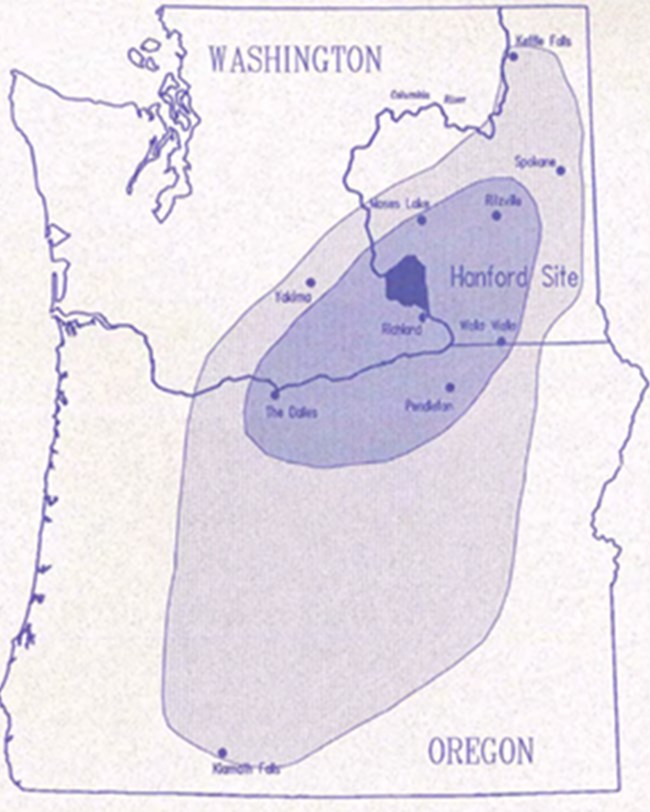

On December 2, 1949, the Atomic Energy Commission and the United States Air Force conducted the “Green Run” experiment at the Hanford Nuclear production complex outside Richland, WA. It was the largest single release of radioactive iodine-131 in Hanford’s history, covering vegetation as far north as Kettle Falls, WA and as far south as Klamath Falls, OR.

Cold War Fears

With the onset of the Cold War, plutonium production at Hanford increased dramatically. When the Soviet Union conducted its first successful atomic bomb test in August 1949, United States government officials feared that the Soviet Union would build a nuclear arsenal. Thus, they needed a way to monitor Soviet nuclear weapons production. The Air Force created a Long-Range Detection Program to develop instruments that could measure and track the spread of radiation from nuclear weapons facilities. To test their instruments, the Air Force first attempted to utilize aircraft that flew over and measured routine radiation released from nuclear facilities at Hanford, WA and Oak Ridge, TN. The initial tests showed that their measuring devices were not accurate enough to record the small amount of radiation that was released. Enter the Green Run.

The Failed Experiment

U.S. Government officials were hoping to develop better methods for detecting Soviet nuclear weapons production. The purpose of the Green Run was to test these methods by tracking and measuring a large volume of particles released into the air at Hanford. In the experiment, fission products from Hanford’s reactors were processed after only 16 days of cooling, rather than the normal 90 to 125 days, in order to replicate the Soviets’ process. This “green,” highly radioactive fuel was then processed, intentionally releasing high quantities of iodine-131 and other radioactive gases, unfiltered, from Hanford’s Chemical Separations “T plant."

Key to the success of the Green Run was favorable weather. The Health Instrument Division of the General Electric Company established five conditions that had to be met. First was a layer of cold air close to the ground. The Division believed that this inversion would protect the ground from stack emissions. There also could not be any precipitation that would hinder measurements from the air. Wind speeds above 200 feet (60.96 m) had to be less than 15 miles per hour (24.14 kph) and come from the west or southwest. Lastly, all conditions had to remain stable long enough for the emissions to be measured.

From the outset, the experiment did not go as planned. Scientists predicted that 4,000 curies of iodine would be released. Analysis after the experiment proved that roughly twice the predicted amount was emitted. Wind directions on the test day went mainly northwest to southeast which dispersed the radioactive material around the state of Washington. Radioactive iodine ended up on the ground in vegetation and water. Vegetation contamination readings by Hanford’s environmental monitoring staff showed 600 times the tolerable amount in Kennewick, WA. Adverse weather on the day of the test doomed its success. Rain caused significant concentrations of radioactive material to fall on Spokane, WA and Walla Walla, WA. Winds throughout the experiment’s run changed direction and scientists lost track of the radioactive release.

Technical Steering Panel of the Hanford Environmental Dose Reconstruction Project, “The Green Run” (Fact Sheet #12, Mar. 1992).

The amount of iodine-131 released during the Green Run is estimated to be around 8,000 curies. Compare this to the approximately 15 curies of radiation released from the Three Mile Island accident in Pennsylvania in 1979. A resident of Walla Walla at the time later pointed out that in the Three Mile Island incident, people were evacuated, but not only was no one evacuated during the Green Run, they were not even made aware that it happened.

Though the Green Run released a considerable amount of radiation, it pales in comparison to the total amount, 739,000 curies of iodine-131, released at Hanford over the period 1944-1972. The people affected from the Green Run and other radiation releases due to accidents or negligence are known as the Downwinders. The Green Run experiment resulted in long-term health problems for many of the Downwinders, such as increased cancer rates and lymphatic illnesses. The Downwinders, or the forgotten peoples of the Green Run, were guinea pigs in a test gone wrong. Connie Nelson, who grew up in Garfield, WA during the Green Run and suffers from thyroid cancer, says painfully “We are like a sacrificed group." The human toll continues to be felt by people to this day.

- Technical Steering Panel of the Hanford Environmental Dose Reconstruction Project, Fact Sheet #12, “The Green Run” (March 1992), in Radiation Health Effects and Hanford, A Resource Book, compiled by the Hanford Health Information Network (June 1995), Eastern Washington University Archives and Special Collections, Cheney, WA.

- Jim Thomas, “New Details of Green Run’s Sorcery,” Hanford Education Action League, Perspective, #10-11 (Summer/Fall, 1992), 21, 26, Eastern Washington University Archives and Special Collections, Cheney, WA.

- Ian Stacy, “Roads to Ruin on the Atomic Frontier: Environmental Decision Making at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation” Environmental History 15, No.3 (July 2010), 431. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/manhattan-project-science-at-hanford.htm

- Trisha T. Pritikin, The Hanford Plaintiffs: Voices from the Fight for Atomic Justice (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2020), 100-101.

- D. E. Jenne, J. W. Healy, “Dissolving of Twenty Day Metal at Hanford” (May 1, 1950) HW-17381-Notes. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/radiation/dir/mstreet/commeet/meet2/brief2/tab_n/br2n1d.txt

- Michele Stenehjem, “Pathways of Radioactive Contamination: Beginning the History, Public Enquiry, and Policy Study of the Hanford Nuclear Reservation,” Environmental Review 13, no. 3/4 (Winter 1989), 103. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3984392