Last updated: January 15, 2026

Article

The Garrison of Fort Warren during the Civil War

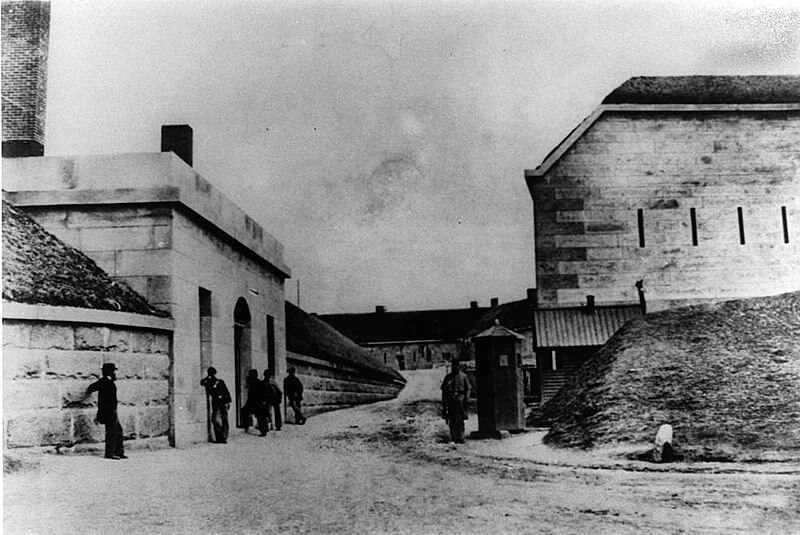

NPS Photo

First Arrivals

At the outbreak of the US Civil War in April 1861, Fort Warren and Fort Independence in Boston Harbor had not yet been garrisoned, which meant there were no soldiers stationed on either island. With fears of a Confederate attack rising, Governor John Andrew sent George Boutwell to Washington D.C. and New York to deliver a letter to the Secretary of War. The letter urged for a military plan to allow for militias to be sent out to the harbor islands. Boutwell received authorization from General John Wool, and Governor Andrew garrisoned both Fort Warren and Fort Independence. The Secretary of War later approved these actions.[1]

The Second Battalion of Infantry arrived on Georges Island on April 29, 1861, under the command of Major Ralph W. Newton. As the first to arrive, the battalion faced the monotonous task of cleaning up debris left behind from construction. To pass the time, the battalion sang popular hymns of the day. They are perhaps best known for "The John Brown Song," which was written during their time at Fort Warren.[2]

A report sent to General John Wool in June 1861, claimed that the fortification had been ruined by the battalion. It described filthy conditions, blocked drains, and poorly located chimneys. While the fort might not have been immaculate, it had been in worse condition before the Second Battalion. The Eleventh, Twelfth, and Fourteenth Regiments all trained on Georges Island before being transferred to the front line. When the Second Battalion disbanded, many of its soldiers joined the Twelfth Regiment.

Leadership at Fort Warren changed frequently. Major General Samuel Andrews commanded Fort Warren and Fort Independence from May to June 1861. Brigadier-General Ebenezer W. Peirce replaced Adams, though he held command for less than a month before he took command of Massachusetts troops at the front. His replacement, Brigadier-General Joseph Andrews remained in command of the harbor island fortifications and Camp Cameron until November 1861.[3]

Life at Fort Warren

Many soldiers complained about the quality of food they received at Fort Warren, and dissatisfaction increased when the Fourteenth Regiment saw that the Twelfth Regiment had been receiving food service from Boston. A sergeant from the Fourteenth Regiment remembered his first meal at Fort Warren: "Each man got about two beans in a pint or warm water- -that was all there seemed to be in the concoction."[4]

Other soldiers held a mock funeral for the original bean that the soup came from. While food rations quickly improved, overcrowded conditions arose as a new problem. When the US Sanitary Commission examined Boston area fortifications in the summer of 1861, the Commission found that soldiers at Fort Warren did not have the proper amount of personal space in their barracks.

Many soldiers of the Eleventh, Twelfth, Fourteenth Regiments had been recruited locally, and as a result had the luxury of welcoming guests on Wednesday and Sundays. As many as 2,000 guests descended upon Georges Island on these days. Eventually these soldiers fell into a routine and enjoyed being on the island in the summertime. This routine proved short-lived, as The Eleventh, Twelfth and Fourteenth Regiments had all left Fort Warren by August. [5]

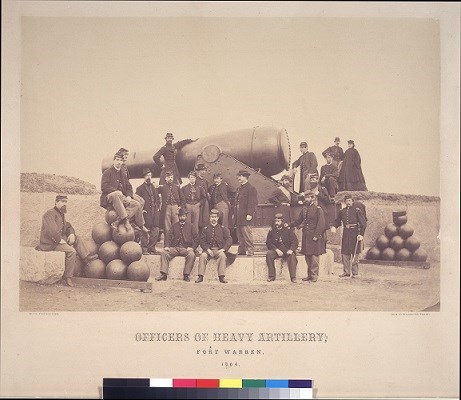

National Archives

Under Colonel Dimick’s Command

Following the departure of the three regiments, Governor Andrew’s assistant military secretary wrote to Lieutenant McPherson requesting permission to keep troops at Fort Warren permanently. Several days later, the government made the decision to use Fort Warren as a prisoner-of-war camp. The Secretary of War permitted the assignment of the Twenty-Fourth Regiment to Fort Warren, until an organization could be found to permanently garrison the fort, Governor Andrew received the authorization to raise three or four companies for service at Fort Warren. Colonel Justin Dimick took command of Fort Warren on October 25, 1861, just days before the first prisoners arrived. Upon Dimick’s arrival on Georges Island, he requested the presence of the soldiers who had been detailed to the fort. On October 29, Dimick reported that six officers and one hundred eighty-four men had arrived. The historian of the Twenty- Fourth recalled their time at Fort Warren as “dark and dreary.” He noted that the accommodations had not been what they had hoped, and they did not like being separated from the rest of the regiment.

The First Battalion mustered into service on November 17, 1861. Raised to be on guard duty at Fort Warren, the battalion arrived on Georges Island on December 3. The Twenty-Fourth Regiment received orders to return to the camp in Readville - soon after the arrival of the First Battalion, leaving Fort Warren on December 7. [6]

The First Battalion arrived on Georges Island unexpectedly and had to wait outside in the cold for an hour before entering the fort. During their time at Fort Warren, Colonel Dimick expected barracks and uniforms to be pristine, and the battalion had a great deal of respect for the Colonel. A food fight that ended with Colonel Dimick being hit in the face with a loaf of bread, only resulted in a minor punishment.

In The Story of the Thirty-Second Regiment, Massachusetts Infantry. Whence it came; where it went; what it saw, and what it did, Colonel Francis J. Parker called Fort Warren their "cradle." Of their work, guarding prisoners, Parker recalled:

seventy-five men…. divided into the interior and exterior guard. During the daytime a line of sentinels enclosed a space in front of the prisoners' quarters, within which they were permitted to exer- cise, and these sentinels at retreat were drawn in to the casemate entrances. Guards were also placed at the sally-port and postern, and near the stair- cases leading up to the ramparts. Outside, a picket line entirely surrounded the fortifications; watch being kept not only to prevent escape from within, but also to forbid the approach of boats from the sea or the shore. [7]

Remaining on the island through the winter, soldiers sought refuge in the sentry box, though the danger of falling asleep loomed over the soldiers.

By the time the First Battalion arrived on Georges Island; soldiers could no longer have guests. They continued to receive gifts, though as time went on the First Battalion grew eager to get to the front. The Battalion received orders to leave on May 21 and eventually became a part of the Twenty-Fourth Regiment.

NPS Photo

The Band of the First United States Artillery joined the First Battalion at Fort Warren before the end of 1861. Prior to his appointment as commander of Fort Warren, Colonel Dimick had served with this regiment, and following the retirement of Colonel Erving in October 1861, Colonel Dimick succeeded him as commander of the regiment. Dimick served in this capacity until 1863. Major Parker described their playing as excellent. Even the prisoners enjoyed their music. The band received orders to transfer to Fort Independence on Castle Island, where they remained until they left for New York in November of 1865.[8]

A Permanent Garrison

The Boston Cadets and the Salem Cadets relieved the First Battalion in May 1862. Under command of Captain Stephen Cabot, they arrived on Georges Island with ten commissioned officers and 25 non-commissioned officers. The Boston Cadets received their food from a Boston caterer, and a June 1862 newspaper falsely noted that the cadets had "disgusting duties being forced upon them." In reality, they had the same duties as other soldiers. Some discontent with the barracks continued, but the cadets eventually fell into a routine. Like their predecessors, they found guard duty to be tedious and boring, but passed the time together by singing and playing chess. When the Boston Cadets left Fort Warren in July; the Seventh Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment replaced them. Little is known about the Salem Cadets; they requested to be transferred due to lack of prisoners, and left Fort Warren in October 1862.

In September 1862, Cabot received permission to recruit an additional artillery company for the fort. By this point, the current garrison had shrunk so small that soldiers had guard duty every third night. With the enlistment term of the Seventh Regiment ending, Cabot also received authorization for a third artillery company. A fourth company completed the battalion and Cabot received the rank of major. Major Cabot took command of Fort Warren, following Colonel Dimick's retirment in 1863.The First Massachusetts Heavy Artillery Battalion stayed at Fort Warren for the remainder of the war, eventually expanding to six companies. Unattached companies assisted at Fort Warren for short periods of time. Major Harvey A. Allen took command in the winter of 1865 after Major Cabot's departure, and remained in command of the until the summer of 1865, when Major John W.M Appleton took command of the fort. Appleton remained in command until August 13, 1865.[9]

Footnotes:

[1] Minor Horne Mclein, Prison Conditions in Fort Warren, Boston, During the Civil War, (Unpublished dissertation, 1955), 4-27.

[2] William Schouler, A History of Massachusetts During the Civil War, (Boston: E.P Dutton & Co Publishers, 1868,) 163; Mclein, Prison Conditions in Fort Warren, Boston, During the Civil War, 28-29.

[3] Schouler, A History of Massachusetts During the Civil War, 163-164.

[4] Mclein, Prison Conditions in Fort Warren, Boston, During the Civil War, 32.

[5] Mclein, Prison Conditions in Fort Warren, Boston, During the Civil War, 29- 36.

[6] Mclein, Prison Conditions in Fort Warren, Boston, During the Civil War, 36- 40; Alfred S. Rowe, The Twenty- Fourth Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteers, 1861-1866, New England Guard Regiment, (Worcester: Twenty- Fourth Regiment Association, 1907), 29-35.

[7] Francis J. Parker,The Story of the Thirty- Second Regiment, Massachusetts Infantry. Whence it Came; Where it Went; What it Saw and What it Did, (Boston: C.W. Calkins & co, 1880,) 2-27; James B. Henry, Memories of Civil War, (New Bedford: F.E. James, 1898), 3-4; Mclein, Prison Conditions in Fort Warren, Boston, During the Civil War, 39-43.

[8] Mclein, Prison Conditions in Fort Warren, Boston, During the Civil War, 39- 60; Major William L. Haskin, "First Regiment of Artillery," in The Army of the United States: historical sketches of staff and line with portraits of generals-in-chief, edited by Theophilus Rodenbough and William Haskin (New York: Maynard, Merrill, & Co. 1896), 301-311.

[9] Mclein, Prison Conditions in Fort Warren, Boston, During the Civil War, 40-60; Bill Stockinger, Background Package to Georges Island, (unpublished), 131-132.