Last updated: September 26, 2020

Article

The Constitution and the Underground Railroad: How a System of Government Dedicated to Liberty Protected Slavery

On August 28, 1787 two of South Carolina’s delegates to the Constitutional Convention, Pierce Butler and Charles Pinckney, suggested a new provision for the draft constitution. The Convention had been debating the new form of government for more than three months. Throughout the summer there had been lengthy and acrimonious debates over how slavery would affect the new form of government. Southerners had demanded, and won, numerous provisions to protect the system of human bondage.

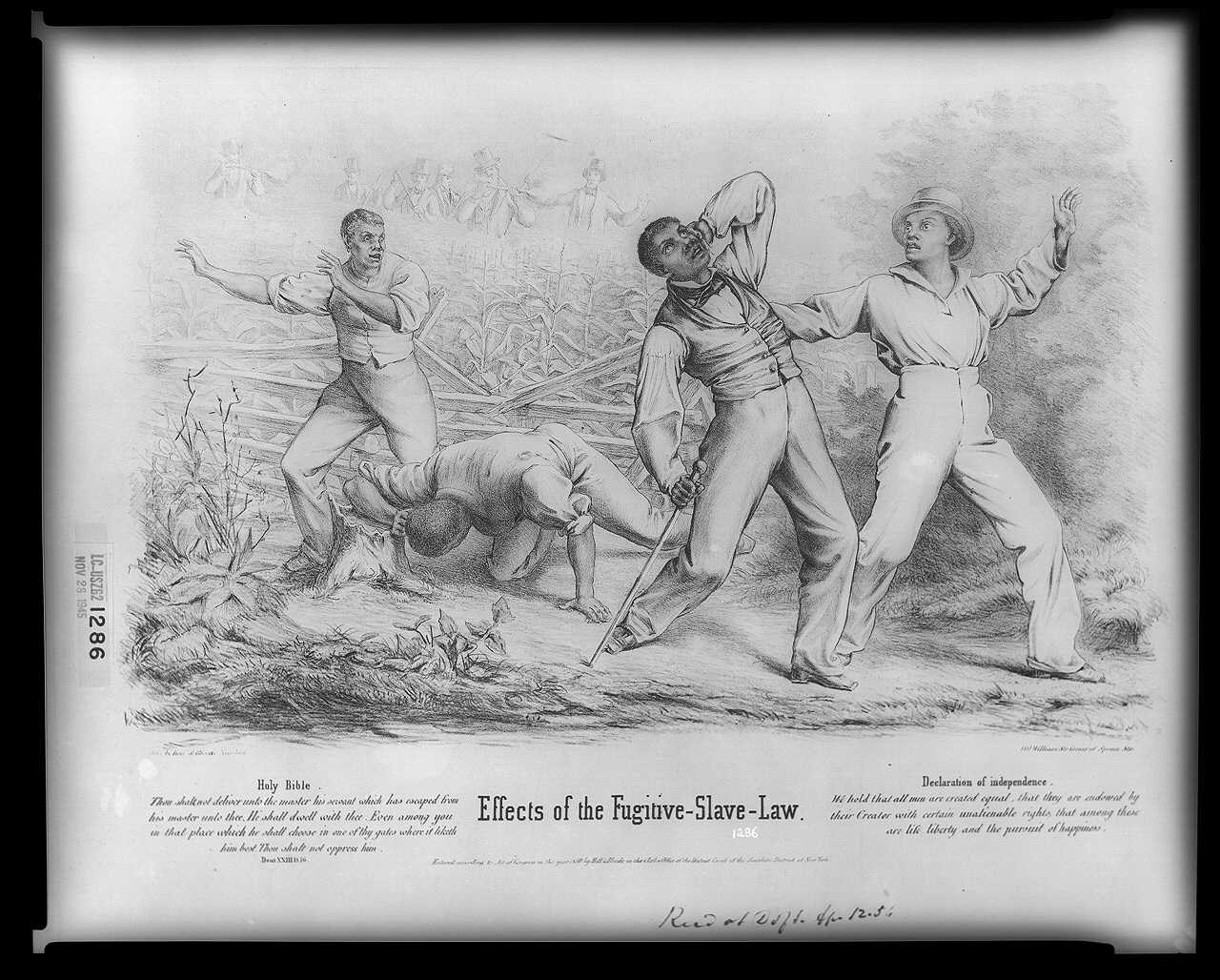

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division (LC-USZ62-6088).

No other social or economic institution received such special treatment. In the three-fifths clause the new Constitution counted slaves to determine representation in Congress, thus increasing the power of the slave states in the House of Representatives and in the electoral college. The Constitution empowered Congress to regulate all international trade, except the African slave trade, which could not be abolished by Congress for at least twenty years. Congress and the states were prohibited from taxing exports, which protected the tobacco and rice grown by slaves. In two different places the Constitution promised that the national government would suppress “domestic Violence” and “Insurrections” which for slaveowners meant only one thing: slave rebellions.

Now Butler and Pinckney demanded that “fugitive slaves and servants” should “be delivered up like criminals” if they escaped into other states. Some northern delegates mocked this demand, asking why their states should spend money and time helping southerners hunt down their “property.” The South Carolinians withdrew their proposal, but that evening there must have been intense conversations among the delegates. The next day, without any more debate or even a formal vote, the Convention approved what became Fugitive Slave Clause.

No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.

Avoiding the word slave, the clause appeared to mean that if a slave escaped to a free state, the free state could not free that person, and any fugitive who was found would be turned over to the person who claimed ownership of the slave. This clause appeared in Article IV of the Constitution, which regulated relations between the states. Thus, the language of the clause and its structural placement implied that this was something that the states would have to work out among themselves.

During the debates over ratification, anti-slavery northerners complained about the slave trade provision and the three-fifths clause, but overlooked the fugitive slave clause. No northerners saw its potential to harm their neighbors or that it might disrupt their society. However, southern federalists pointed to the clause as a reason to ratify the Constitution. General Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (whose younger cousin had introduced the clause) bragged to the South Carolina state legislature: “We have obtained a right to recover our slaves in whatever part of America they may take refuge, which is a right we had not before.” Similarly, at the Virginia convention Edmund Randolph quoted this clause to show that the Constitution protected slavery. He noted that “Everyone knows that slaves are held to service and labor.” He argued that under the Constitution “authority is given to owners of slaves to vindicate their property” because it allowed a Virginian to go to another state and “take his runaway slave” and bring “him home.”

No one at the Convention seemed to contemplate that the federal government would act as the agent for slaveowners. But just a few years after ratification of the Constitution the issue of fugitive slaves and the extradition of criminals came before Congress. Pennsylvania had demanded that Virginia return a fugitive from justice, charged with kidnapping a free black. Virginia’s governor refused, arguing the free black was in fact a fugitive slave and so no crime had been committed. The Governor Thomas Mifflin of Pennsylvania asked President Washington to intervene and the issue was soon in the hands of Congress. The result was a 1793 law which regulated both the return of fugitive criminals and runaway slaves. Under this law slaveowners had to locate their slaves in the North (which was not always easy), obtain a certificate of removal from a state or federal judge, and then bring their fugitive home. People harboring fugitive slaves could be fined up to $500 (a significant amount of money at the time) and also be sued for the value of any slave not recovered. In response to southerners forcibly removing blacks from the North (including free blacks), most of the northeastern and Mid-Atlantic states passed personal liberty laws which required state judges to hold hearings on the status of any blacks who might be claimed as fugitive slaves. These state laws contained significant penalties for people who did not follow these rules.

However, in 1842 the U.S. Supreme Court, in Prigg v. Pennsylvania, held that all these laws were unconstitutional, because according to the Court, Congress had the exclusive power to regulate the return of fugitive slaves. This ruling stood the history of the Fugitive Slave Clause on its head, and completely ignored both the text and structure of the Constitution. In response, a number of northern states passed laws to prevent the use of state property (including jails) for the return of fugitive slaves and also prohibited state officials from acting in fugitive slave cases.

This left southerners in a quandary. Prigg was a powerful proslavery decision which put the full force of the federal government behind efforts to recover runaway slaves. But, at the time there was no national law enforcement system and most states had only a single federal judge. Without the cooperation of the northern states, returning fugitive slaves would be difficult.

In response to Prigg, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. It created a national system of law enforcement, with federal commissioners appointed in every county in the nation. Alleged slaves were brought before these commissioners, who would decide on their own, without a jury or a formal trial, if someone was a slave. The commissioners were authorized to use state militias, federal marshals, and the Army and Navy to return fugitive slaves. No court in the nation could issue a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of an alleged fugitive. Anyone helping a slave escape could be imprisoned for six months and fined the enormous sum of one thousand dollars. The law made mockery of the due process rights found in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. It also interfered with right of the northern states to protect their free black residents from being claimed as a fugitive. Because it denied alleged slaves the right to a jury trial, the right to habeas corpus, and the right to even testify at their own hearing, many northerners condemned it as a law which legalized kidnapping.[1]

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division (LC-USZ62-1286).

Under this law about 1,000 Africans Americans would be sent back to the South between 1850 and 1861. Numerous abolitionists would be fined and jailed for helping freedom seekers escape along the Underground Railroad. Throughout the North there was strenuous opposition to the law, in state legislatures, in courtrooms, and in the streets. In 1862 Congress prohibited the use of soldiers to enforce this law, which was finally repealed in 1864.

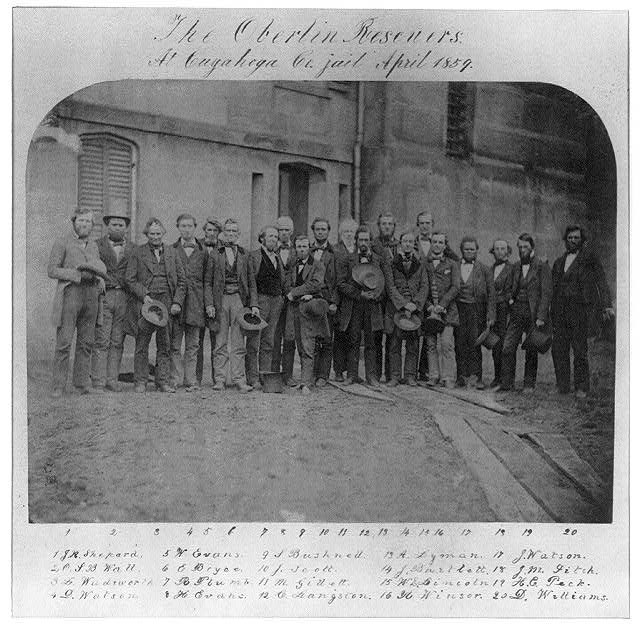

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division (LC-USZ62-73349).

As we celebrate Constitution Day, it is important to remember that this document protected slavery and set the stage for the federal government to hunt down and arrest people, whose only crime was the color of their skin and their desire to benefit from “the Blessings of Liberty” that the Constitution claimed it was written to achieve.

The Constitution and the two fugitive slave laws also led to thousands of northerners – black and white – secretly acting to protect blacks from slave catchers. In some places, such as upstate New York and northern Ohio, the 1850 law was virtually unenforceable, as the average, usually law abiding citizens, participated in the Underground Railroad, choosing to support human liberty and fundamental justice, even when the laws of the United States and the Constitution itself criminalized such activities.

Paul Finkelman, Ph.D. is the President of Gratz College in greater Philadelphia. He is the author of more than 50 books and hundreds of articles. His most recent book, Supreme Injustice: Slavery in the Nation’s Highest Court was published by Harvard University Press in 2018.

Want to learn more?

The National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Program and Gratz College partnered to provide a webinar where the author of this article, Dr. Paul Finkelman, further explores the connections between the Underground Railroad and the Constitution. To access a recording of the webinar, please click on the link below.

-

The Underground Railroad and the Constitution

Presentation by Dr. Paul Finkelman of Gratz College and Deanda Johnson of the Network to Freedom.

- Duration:

- 1 hour, 11 minutes, 37 seconds