Last updated: December 15, 2020

Article

“Let it be placed among the abominations!”: The Bill of Rights and the Fugitive Slave Laws

"[A] bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular, and what no just government should refuse, or rest on inference."

-Thomas Jefferson, Letter to James Madison, December 20, 1787.

Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection

Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

On December 15, 1791 Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson certified that ten proposed amendments to the Constitution, known as the Bill of Rights, had been ratified. Today marks the 229th anniversary of that ratification. Drafted by James Madison in 1789 but modified by debate in the House and the Senate, the amendments responded to fears that the new national government might trample on basic liberties.[1] Among other things, the amendments prohibited Congress (but not the states) from limiting freedom of speech, press, assembly, and religious practice, or denying people fair trials and due process of law. For the most part the amendments worked relatively well.

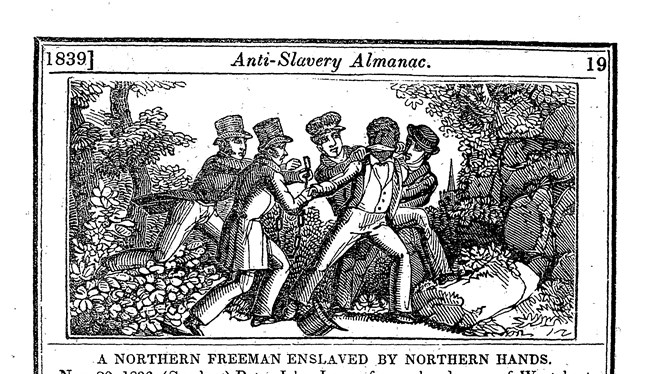

However, Congress flagrantly ignored the Bill of Rights in the Fugitive Slave Laws of 1793 and 1850. These laws denied alleged slaves fair trials, due process of law, or even the right prove their freedom in court. The fugitive slave laws clearly violated the fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh amendments, as well as the Constitution’s protection of the right to the writ of habeas corpus.

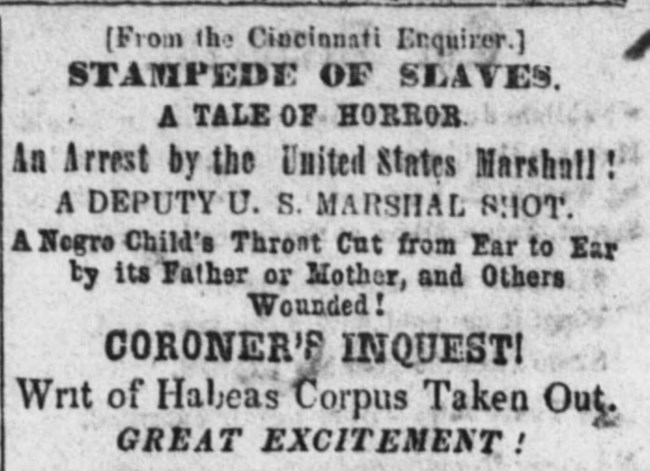

Library of Congress

The Fourth Amendment guarantees the right of the people “to be secure in their persons” from “unreasonable searches and seizures.” No search or seizure under the authority of the federal government can take place without a warrant issued by a judge. The warrant has to be based on a sworn statement describing the person or evidence to be seized or the place to be searched. However, the 1793 and 1850 laws authorized private individuals to “seize or arrest” alleged fugitives without any warrant or other judicial scrutiny. In clear violation of the Fourth Amendment, the law allowed slave catchers without warrants to seize blacks in public and to invade private homes or buildings in the search of fugitive slaves. For example, in 1856 a group of Kentucky slave catchers and a federal marshal stormed into the private home of a free African American in Cincinnati without a warrant, to seize Margaret Garner and her family. During this raid, which clearly violated the Fourth Amendment, Garner succeeded in killing her daughter, rather than see her returned to slavery. Garner and the rest of her family were subsequently taken back to Kentucky to be re-enslaved.[2] Storming a private home with weapons drawn in violation of the Fourth Amendment illustrated how the violence of slavery threatened the liberties of the free people, black and white, in the North, while denying fundamental due process to blacks accused of being fugitives, including many free people.

The Fifth Amendment declares that no person can “be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” But there was no due process in fugitive slave cases. Under the 1850 law the alleged fugitive was not allowed testify on his or her own behalf, even to assert a case of mistaken identity. Under that law a judge received $5.00 if he decided in favor of freedom, and $10.00 if he decided in favor of the slaveowner. This appeared, to many people, to be a bribe to buy justice for the slaveowner.

The Sixth Amendment requires that trials be before an “impartial jury” and that defendants have a right to subpoena witnesses on their behalf and have assistance of counsel. The Seventh Amendment guaranteed jury trials in civil cases. But the fugitive slave laws ignored these constitutional protections. The 1793 law did not provide a jury trial and allowed any magistrate – even a lowly justice of the peace – to order that a black person be turned over to a slave catcher after a summary hearing. In response to this law, some northern states passed “personal liberty laws” to protect free blacks from being kidnapped.[3] In response to growing hostility to the return of fugitive slaves, the 1850 law specifically denied alleged fugitives the right to a jury trial.

Library of Congress

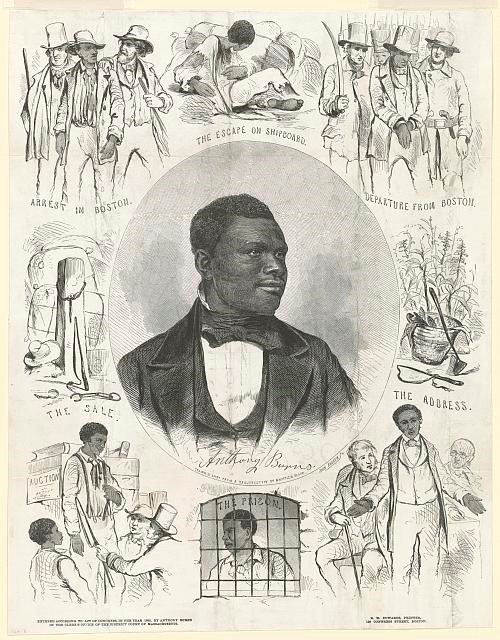

Under both laws hearings were summary affairs, often conducted immediately after an alleged slave was seized, giving the person no time to prepare a defense, to find an attorney, or to summon witnesses. For example, in 1854 police in Boston arrested Anthony Burns in the early evening on a phony robbery charge, kept him isolated in jail all night, and brought him before a U.S. commissioner for a summary hearing first thing in the morning. The commissioner hoped to quickly listen to the slave catcher, write out all the papers, and send Burns on his way to Virginia before anyone knew about the case. However, the lawyer Richard Henry Dana walked by the courtroom, saw what was happening, and immediately intervened on behalf of Burns. Dana shamed the commissioner to actually hold a real hearing with evidence and witnesses. Despite conflicting testimony, the commissioner (who was also a part time professor at Harvard Law School) sent Burns back to Virginia. The fame of the case led to people raising money to buy his freedom. The commissioner, Edward G. Loring, who was also a state probate judge, became a pariah in the community. He was stripped of his judgeship and not renewed at Harvard, and eventually moved to Washington, D.C. This famous case demonstrated how the law fundamentally violated the Bill of Rights.[4]

The main body of the Constitution protects the right to a writ of habeas corpus. Known in Anglo-American law as “the Great Writ,” habeas corpus ensures that people arrested will be brought before courts for a trial. It prevents the government from throwing people in jail without charges. This right connects to the guarantee of due process in the Fifth Amendment and the jury trial provision of the Sixth Amendment. While not in the Bill of Rights, access to the Writ of Habeas Corpus has always been seen as a basic right. It is fundamental to a free society because it prevents the arbitrary or illegal imprisonment of people. It is truly the great writ of a free society. Thus, the Constitution provides that “The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.”

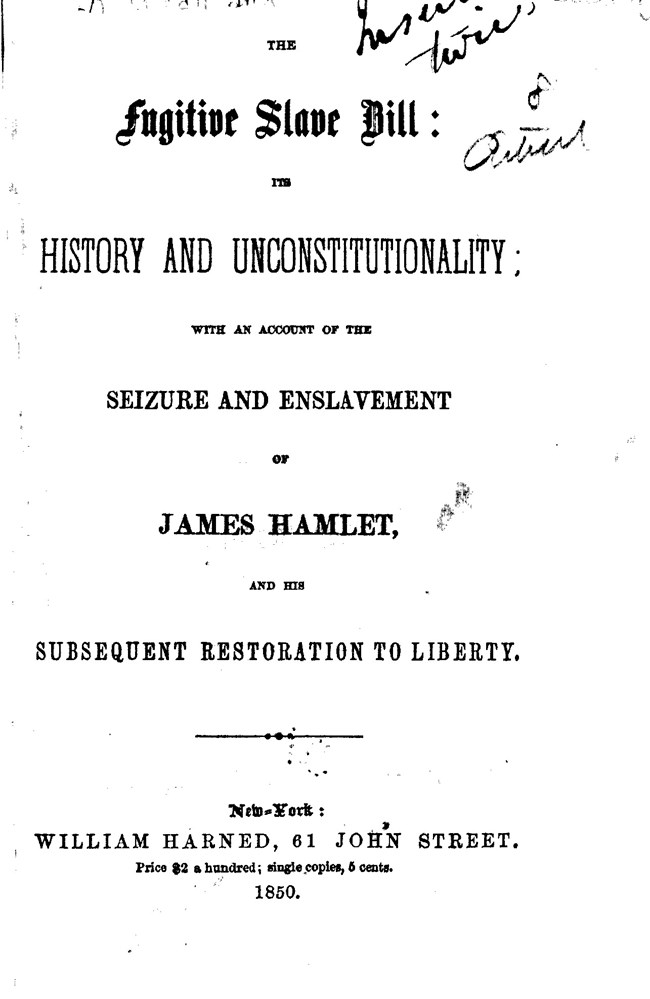

But the 1850 Law brazenly prohibited the use of the writ – suspended the great writ – in fugitive slave cases. Once a magistrate, commissioner, or judge issued a certificate to remove a slave from a free state, no court could question the right of the slave catcher to take his human “property” to the South. Thus, a justice of the peace, with no legal training, could issue a certificate of removal after a quick and informal hearing, and no judge – not even a state supreme court justice, a United States District judge, or a justice of the United States Supreme Court – could issue a writ of habeas corpus to examine the facts of the case or if the law had been followed. It is hard to imagine a more unjust law or one that so blatantly disregarded the fundamental rights enshrined in the Constitution.

The 1850 act is universally considered to be among the most unfair and illegitimate laws ever passed by Congress. Throughout the North black leaders and many white lawyers, ministers, and politicians denounced this statute as a blatant attempt to subvert the Bill of Rights and to buy justice to support slavery. There were hundreds of sermons similar in title and substance to one Rev. Nathaniel Colver’s gave in Boston shortly after the passage of the 1850 law: “The Fugitive Slave Bill; or, God's Laws Paramount to the Laws of Men: a Sermon, Preached on Sunday, October 20, 1850.”[5] This sermon illustrates how many northerners responded to the 1850. In the streets, the law led to riots and rescues in Boston, Syracuse, Milwaukee, Wellington, Ohio, and Christiana, Pennsylvania.[6]

Ironically, the 1850 law, which stained the American statute books and made a mockery of the Bill of Rights, did nothing to stop enslaved people from running away – people seeking freedom did not worry about the law, they worried about safely making it to the North, Canada, or Mexico.[7] Thus, Congress not only ignored and trampled on the Bill of Rights, but did so with no meaningful results. The laws also were not very effective in helping southerners regain their slaves. Between 1850 and the beginning of the Civil War fewer than 400 fugitives were returned to the South, even though at least ten thousand slaves ran to the North in that decade alone.[8] The laws infuriated many northerners, embarrassed the national government when it proved incapable of enforcing them, and led to riots and rescues. Rather than protecting the “property” of slaveowners, the laws helped garner support in the North for political candidates who stood up against slavery and stood up for freedom.

This shift in northern culture and politics infuriated virtually all white southerners. In 1793 many white northerners were not focused on the existence slavery in the South, even as all the Northern states had either ended slavery, were in the process of gradually ending it, or, in two of them, debating how to end it. By 1804 every northern state had either ended it outright or passed gradual abolition laws to end it gradually. Starting in the 1820s northern legislatures passed “personal liberty laws,” to protect their black neighbors from being arbitrarily removed to the South without a fair hearing. These laws were also designed to prevent the kidnapping of free blacks. In the 1830s the highest courts in New York and New Jersey declared that the 1793 was unconstitutional. When the Supreme Court struck these laws down, in Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842), many northern states refused to cooperate with the return of fugitive slaves, because they were no longer able to prevent the kidnapping of their free black neighbors.[9]

The enforcement of the 1793 and the 1850 fugitive slave laws impressed upon northerners that a denial of the liberties in the Bill of Rights threatened all people, white and black, enslaved and free. The laws drove home to northerners that slavery in the South jeopardized their own liberties and their own communities in the North. Hostility to slavery in the North grew each time a fugitive was returned. The 1850 law with its harsher penalties and obvious violations of the Bill of Rights increased opposition to the rendition of fugitive slaves. This story – of fundamental liberties and the Fugitive Slave Laws – reminds us today, more than a century and a half after the end of slavery – of the importance of the Bill of Rights for all people in the United States.

Paul Finkelman, a legal historian, is the president of Gratz College in greater Philadelphia. His most recent books are, Supreme Injustice: Slavery in the Nation’s Highest Court (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018) and Defending Slavery: Proslavery Thought in the Old South (Boston: Bedford Books, 2019).

Footnotes

The article takes its title from “The Fugitive Slave Law,” Hartford, CT, 1850, https://www.loc.gov/item/98101767/.

[1] The primary sources on the adopted of the Bill of Rights are found in Helen E. Veit, Charlene Bangs Bickford, and Kenneth R. Bowling, Creating the Bill of Rights: The Documentary History From the First Federal Congress (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991). For an analysis of the evolution of the amendments, see Paul Finkelman, “James Madison and the Bill of Rights: A Reluctant Paternity,” 1990 Supreme Court Review (1991): 301-47.

[2] Nikki M. Taylor, Driven Toward Madness: The Fugitive Slave Margaret Garner and Tragedy on the Ohio (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2016).

[3] Thomas D. Morris, Free Men All: The Personal Liberty Laws of the North (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974).

[4] Paul Finkelman, “Legal Ethics and Fugitive Slaves: The Anthony Burns Case, Judge Loring, and Abolitionist Attorneys,” Cardozo Law Review, 17 (1996): 1793-1858.

[5] Boston: J.M. Hewes and Company, 1850. Available on the website of the Library of Congress: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/rbc/rbaapc/05900/05900.pdf

[6] See for example, H. Robert Baker, The Rescue of Joshua Glover: A Fugitive Slave, the Constitution, and the Coming of the Civil War (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2007).

[7] The best place to start on the history of enslaved Americans seeking freedom is John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger, Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

[8] Stanley W. Campbell, The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1970) found that only 366 slaves were returned to the South under the law, while an estimated 10,000 escaped in that decade.

[9] Paul Finkelman, Chief Justice Hornblower of New Jersey and the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793, in Paul Finkelman, ed., Slavery and the Law (Lanham, Md.: Roman and Littlefield, 1998) 113. Paul Finkelman, “Prigg v. Pennsylvania: Understanding Justice Story's Pro-Slavery Nationalism,” Journal of Supreme Court History, 2 (1997): 51-64.