Last updated: March 26, 2024

Article

Submerged Bug Hotels Tell a Story about Clean Water

NPS/R. Damstra

If we were to try and count all the aquatic macroinvertebrates (insects) in the over 200-mile-long St. Croix National Scenic Riverway (Riverway), we would shortly conclude that their numbers are ad infinitum, or nearly unlimited. Yet, using Hester-Dendy samplers—the equivalent of “bug hotels”—we can collect and identify macroinvertebrates, which gives us an idea of the water quality at that spot.

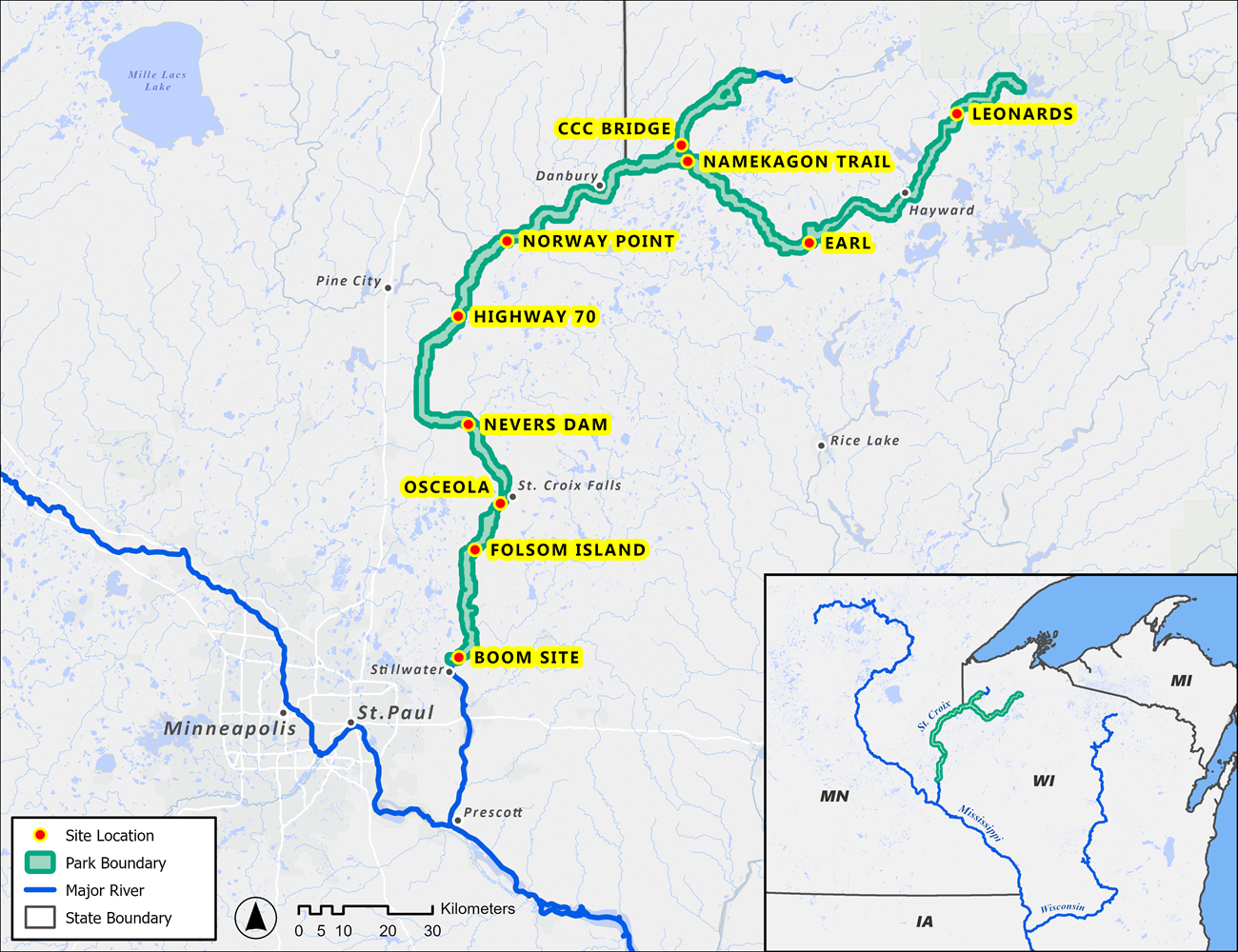

We put Hester-Dendy samplers in the river for six-weeks in the summer. Park staff have collected macroinvertebrates at four sites annually since 2016. Each of the sites is co-located with freshwater mussel beds, an important park natural resource. In 2019, Great Lakes I&M Network staff added seven more sites throughout the Riverway that are also routinely monitored for water quality. Together, these eleven sites give us an overall sense of river health.

Map: NPS/K. Roberts

The ABCs of IBIs

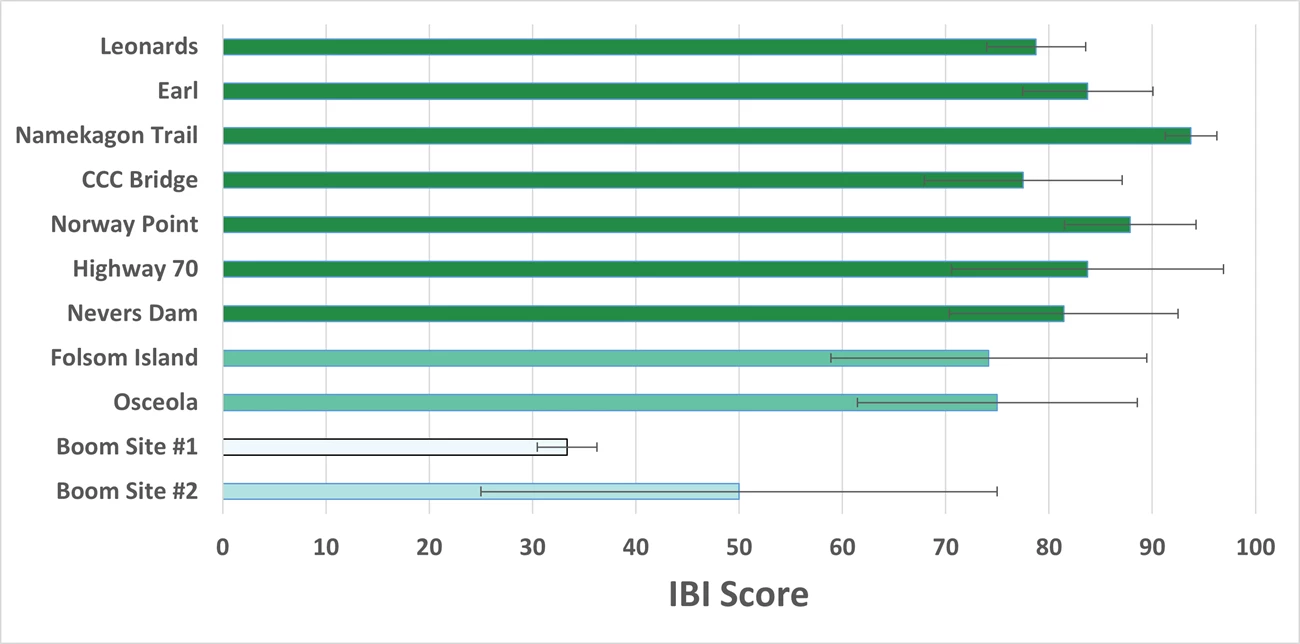

Macroinvertebrates have long been used as an indicator for water quality in streams and rivers. Most live in rivers for a year or more during their immature stages, and because of their limited mobility, they act as integrators of a site’s water quality. We can use information about the number and type of macroinvertebrates we collect to calculate an Index of Biotic Integrity (IBI). That number gives us a sense of whether the river is being affected by things that could alter how many and what types of macroinvertebrates are colonizing the plates. Common stressors include warm water temperatures, low flow, low dissolved oxygen, too much sediment, and possibly pollution from toxic substances. Low IBI scores indicate one or more of these stressors are affecting river macroinvertebrates, whereas higher scores indicate healthier and cleaner water.

IBI scores for almost all the sites we monitor indicate the aquatic macroinvertebrate communities are in good or excellent condition. Two sites farthest downstream—Boom Sites #1 and #2—have the lowest scores. We only have three years of data for these two sites, located just before the river enters Lake St. Croix. Additional years of monitoring will help us to understand if their IBI scores are accurate or if, given the proximity to Lake St. Croix, those sites are appropriate for the monitoring methods (i.e., Hester-Dendy samplers) we are using. Overall, with enough years of data, we can use IBI scores to assess trends in macroinvertebrates and, therefore, river health at all the sites we are monitoring.

We Aren’t the Only Game in Town

Nearly all the aquatic monitoring done on the Riverway, including the macroinvertebrate sampling by NPS, takes place in the context of similar work by other agencies. For example, the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency periodically monitors macroinvertebrates in the Riverway through their Large Rivers Monitoring Program. During their work on the St. Croix River in 2017–2018, they found healthy communities of macroinvertebrates at sites spanning a 128-mile stretch of the river that makes up the border between Minnesota and Wisconsin. They plan on repeating that work in 2028. Also, in past years, Metropolitan Council Environmental Services monitored macroinvertebrates in Lake St. Croix, at Stillwater, Minnesota, and in Prescott, Wisconsin, just before the lake drains to the Mississippi River.

Our monitoring is designed to be compatible with both Minnesota and Wisconsin protocols so our data can be included with theirs to assess the overall health of the Riverway, including whether certain areas are impaired.