Last updated: February 20, 2025

Article

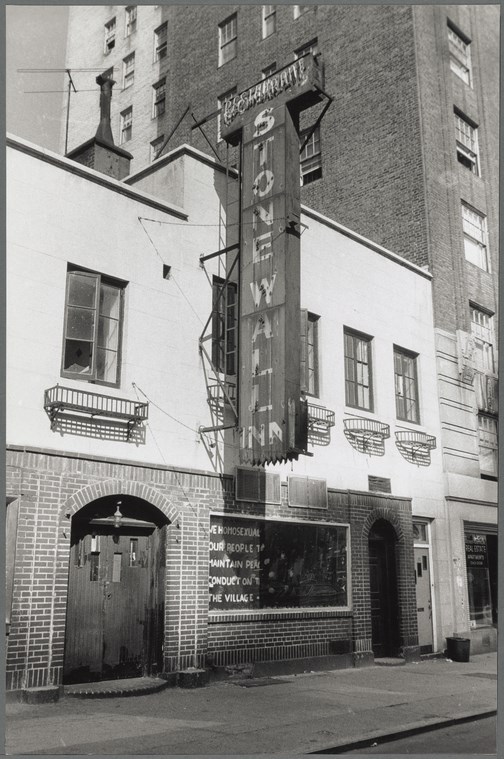

Stonewall National Monument Cultural Landscape

NPS

Diana Davies / Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library

Introduction

The 1960s was a tumultuous era in American history as different groups came together to fight for rights. Events from the anti-war demonstrations against involvement in Vietnam to the Civil Rights and women’s rights movements defined the period as one of change. Similarly, the modern movement for gay and lesbian rights organized near the end of the decade at Stonewall, galvanized and led by many who had previously marched for the rights of others and who were now demanding rights of their own.

The uprisings at Stonewall Inn and the surrounding area, which took place from June 28 to July 3 in 1969, were a major catalyst in the fight for gay rights. During this time, homosexuality was illegal in many states and bars in New York were prohibited from serving alcohol to homosexuals.

Many members of the gay and lesbian community kept their identities secret due to fear of social and legal repercussions. Nevertheless, gay and lesbian bars, such as the Stonewall Inn, existed. Owned and operated by the mafia who paid off the police to prevent raids and closures, these bars were lively places where patrons were free to mingle and be themselves.

Despite bribes from the mafia, the police still occasionally raided the bars, which usually prompted patrons to quickly flee to avoid arrest. Yet, on Saturday, June 28, 1969, when undercover police officers raided the popular Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, Manhattan, the reaction was different. This time, people fought back, making the Stonewall Monument nationally significant for its association with the start of the modern LGB civil rights movement.1

Ewing Galloway / Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy Collection, The New York Public Library

Landscape History

The Stonewall Inn, located on 51-53 Christopher Street in Greenwich Village, lower west side Manhattan, was originally built in 1843 and 1846 as a set of horse stables, composed of two separate, two-story buildings. In 1930, the buildings were combined under a single exterior facade, renovated, and then reopened as a restaurant called Bonnie’s Stonewall Inn. After the restaurant closed in 1966, the building was converted into a gay bar the following year and named The Stonewall Inn.

The bar’s dimly lit interior was painted black but overall, the Stonewall Inn kept many of the architectural features from its 1930s design, such as the exterior, red brick façade, the brick ground on the first floor, and the stucco plaster on the second floor. At first, the bar exclusively served gay men but by 1969, it had opened its doors to women and drag queens as well.

The Stonewall Inn’s location on Christopher Street was no coincidence as that area already had a long history as a welcoming refuge for the gay and lesbian community in New York. The oldest street in the Village, Christopher Street is at the heart of urban life and features a variety of architecture styles and brick buildings, from Art Deco to Tudor-style. The area surrounding the Stonewall Inn seems disorganized in comparison to the rest of Manhattan; it is one of the only areas in the borough that doesn't follow the rectangular grid system. Instead, today’s street system in Greenwich Village follows an older plan laid out by Dutch settlers in the 17th and 18th centuries. Therefore, its streets intersect with each other at seemingly random angles.

NPS

The community life was as unique and as diverse as the physical characteristics of the neighborhood. After the Prohibition ended in 1934, the mafia established many illicit gay bars throughout the Village and on Christopher Street, including the Stonewall Inn in 1967. During the 1960s, many drag queens and gay men openly gathered at the piers at the Christopher Street waterfront, where they could publicly stroll around with their partners without fearing harassment. The world’s first openly gay bookstore, The Oscar Wilde Bookshop, also opened in 1967.

Across from the Stonewall Inn is Christopher Park, one of the few public places in the Greenwich Village area and thus a central component to the community on Christopher Street. Created in 1837, the triangular parcel of land had become popular with gay youth and homeless New Yorkers by the 1960s. Like the Stonewall Inn, the park was a meeting place where members of the gay and lesbian community could safely congregate, plan, and express their demands for civil rights. The physical and ideological proximity between the park and the Stonewall Inn resulted in many park-goers joining forces with the bar patrons on June 28, 1969 to protest discrimination.

NPS

The riots began after police officers began detaining patrons who had no identification or were dressed in drag while forcing everyone else outside. Normally, patrons would have fled the scene as quickly as possible, but in the early hours of June 28, 1969, they formed a large crowd outside the bar. Soon, they were joined by people at Christopher Park as well as by other members of the community, due to the bar’s close location to two subway stations and pay phones, which allowed word of the raid to quickly spread.

Initially, the crowd taunted the police, but as officers began violently hauling people away in the back of police vans, the crowd became agitated and indignant. Many threw pennies, bricks, and beer bottles at the officers in protest, resulting in serious confrontations between the LGB-supporting crowd and the police. Police and their reinforcements had difficulty securing the area due to the maze-like layout of the streets surrounding the Stonewall Inn and Christopher Park. Demonstrators who knew the neighborhood could easily evade the police by turning onto one of the many smaller, intersecting streets, then loop back around on Christopher Street to join in the uprisings once more.

The riots lasted for almost a week. During this time, the bar was set on fire, the interiors destroyed, and windows were smashed. Every night, thousands of people converged onto Christopher Street, demanding civil rights for the gay community. This signified an abrupt change in how LGB protests of the past had operated. Very few people had ever participated in such protests, and those that did behaved in a conservative, quiet manner. The crowds at Stonewall, however, were loud, boisterous, and represented a variety of people; from the homeless LGB people in the park to the revolutionary drag queen, Marsha P. Jones. Thus, while the Stonewall Uprisings were not the beginnings of the struggle for gay and lesbian rights, it was the beginning of a more open, more assertive, and more diverse fight.

NPS

NPS / Schenck

The legacy of Stonewall can be seen in its aftermath. Only sixty organizations dedicated to gay rights existed prior to Stonewall. In the years immediately following the riots, there was an explosion in the number of new groups forwarding LGB rights across the country, such as the Gay Liberation Front. By 1970, there were at least 1500 groups.

The following year, a parade on Christopher Street was organized to commemorate the events at Stonewall as well as to demonstrate how the community would no longer be made to feel ashamed of their identities. Instead, they would defiantly embrace them with pride. Over the years, the number of such parades and attendees grew exponentially, and eventually turned into the country-wide Pride celebrations which take place annually in June. The events at Stonewall ushered in a new era of the civil rights movement, one which would not be silenced or quietly advocated for in the shadows.

On June 24, 2016, President Barack Obama designated the Stonewall National Monument in anticipation of the 50th year anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising. The monument is the first national park site dedicated to gay and lesbian history.

NPS

Landscape Description

Today, the Stonewall National Monument encompasses 7.7 acres of land, the historic sites, and streets which witnessed the action of the 1969 Stonewall Uprisings, including the Stonewall Inn, Christopher Park, Christopher Street, and parts of Grove Street, Waverly Street, Gay Street, Greenwich Avenue, West 4th Street, and 6th Street. Stonewall Inn today largely reflects the structure of the building in 1969 with some interior changes. The western section still houses a bar, called Stonewall Inn in honor of the uprisings, while the eastern section is a commercial building which houses a few businesses. Christopher Park also retains its 1969 appearance. The park is still surrounded by an elegant, iron fence with an arched entrance. The eastern portion of the park contains trees, shrubs, ivy and a statue of Civil War general, Philip Henry Sheridan. The western area features beds of annual and perennial flowers and a plaza with benches.

In the late 1970s, to commemorate the 10th year anniversary of the Stonewall Uprisings, American artist George Segal created the sculpture “Gay Liberation” to place in the Christopher Park. The first piece of public art dedicated to gay rights, the bronze sculpture is painted white and depicts two life-sized couples – a standing pair of men and a seated pair of women. Due to funding issues however, the monument was not installed in Christopher Park until 1992. To better highlight the sculpture, landscape designer Philip Winslow redesigned the surrounding park by installing new brick paths and benches.

NPS / Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation

NPS

Stewardship

Today, the Stonewall Monument is open to the public. The Stonewall Inn and adjacent commercial building complex are privately owned, the streets belong to and are maintained by New York City, and Christopher Park is administered by the National Park Service. As most of the monument is comprised of public places, the site is easily accessible at nearly all times with no tickets or prior registration needed, although privately organized tour groups are a popular option for visitors.

In addition to walking along the same streets where protestors fought for gay and lesbian rights, visitors can gain further knowledge about the events of Stonewall through the physical and virtual Fence Exhibit. Illustrative panels on the fence surrounding Stonewall National Monument explain the story of Stonewall and the modern fight for LGB civil rights to educate inquiring visitors and help ensure that the legacy of Stonewall lives on.

NPS

Historic Designation Facts

- Cultural Landscape Type: Designed, Historic Site

- National Register Significance Level: National

- National Register Significance Criteria:

A – Associated with events significant to broadpatterns of our history

C – Embodies the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction

- National Historic Landmark

- Period of Significance: 1969

More on this Cultural Landscape

-

Stonewall National Monument Landscape Cultural Landscape Inventory park report

-

Federal Register - Establishment of the Stonewall National Monument

-

LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History

-

"1969: The Stonewall Uprising" (Library of Congress Resource Guide)

1. This terminology and its uses are dynamic. Historic and cultural contexts contribute to the understanding of identity and its connection to place.