Last updated: March 6, 2023

Article

Spanish Florida: Poor in Metals, Rich in Waterways

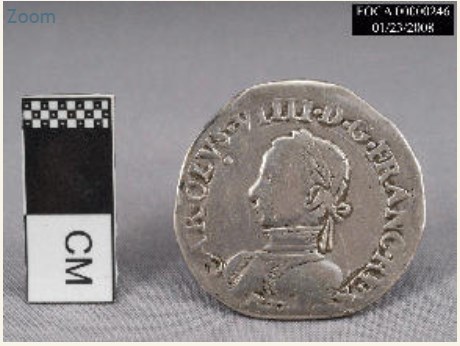

Hernando de Soto was one of several Spanish explorers and conquistadors in the 16th century who explored Florida looking for possible treasures of gold and silver. Through his exploits in Central America, particularly against the Inca Empire in Peru, De Soto acquired wealth and fame as a conquistador. This led to his appointment as Governor of Cuba by Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (Charles I of Spain). Emperor Charles V also granted De Soto permission to lead an expedition to conquer and explore Florida for wealth and a possible land route to Mexico.

From analyses of four written accounts of De Soto’s expedition and archaeological findings, most scholars believe that De Soto left Cuba and arrived in Florida near present day Tampa in May 1539. His entourage included an estimated 1000 men, 250 horses, several hundred pigs, and a substantial number of dogs. De Soto immediately set out to establish his power among the natives he encountered. He and his men pillaged villages, mutilated, burned, and even fed Native peoples to their dogs. They also raped their women, enslaved thousands, and decimated the lands of uncooperative tribes.

Through brute force, advanced metal weaponry, the horse and hound, as well as disease, De Soto and his men subdued Native peoples as they made their way through the southeast in search of riches. Hundreds of Spaniards and thousands of Natives died during their voyage. It is believed that De Soto and his expedition made it as far as Arkansas. They indeed reached the Mississippi River and are thus credited as the first Europeans to discover the Mississippi. It was near this river that Hernando de Soto died of fever on May 21, 1542. His body was shrouded with blankets filled with sand and sank in the Mississippi River to maintain the belief that he was a god among the Natives. De Soto and his expedition never found the riches they sought, instead they found shell objects, mica, and copper. A remnant of about 300 men survived the expedition. This remnant constructed boats and sailed down the Mississippi into the Gulf of Mexico safely to Spanish ports. Disappointed by the lack of precious metals, the Spanish turned their attention away from Florida, at least for a while.

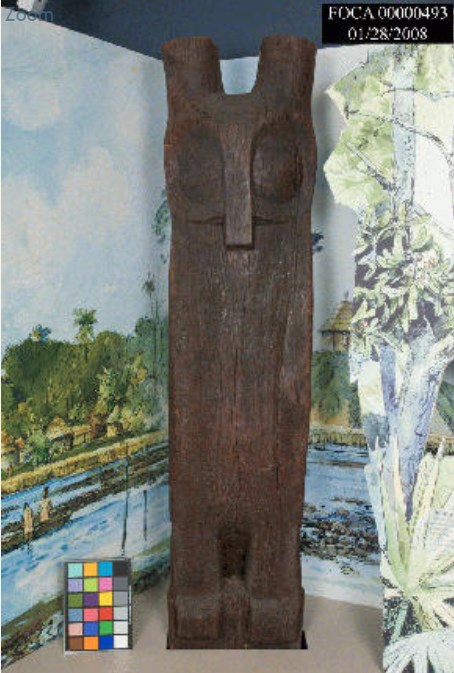

Just to the north, the French were experiencing a religious revival that challenged the Roman Catholic Church. French Huguenots or Protestants were being persecuted because of their faith. One solution was to allow Huguenots the opportunity to leave France and settle in the New World. This would expand France’s empire and possibly bring riches to the throne. In February 1562 Jean Ribault led the first exploratory expedition to Florida. He arrived in May and constructed the Ribault Monument on present day St. John’s River in honor of King Charles IX and his claim to Florida. Ribault wrote detailed accounts of Native Timucuan peoples. He recorded their appearance, subsistence and religious practices, and government structure. Initial encounters were cordial. Thus, when an estimated 300 soldiers, elites, laborers, artisans, and women arrived in 1564 under the leadership of Rene de Boulaine de Laudonniere, the Timucuans welcomed them. They even assisted the French colonists in building the first permanent European settlement in North America at La Caroline on St. John’s River. This settlement included a village and Fort de la Caroline (Fort Caroline). The colonists were mostly Huguenots seeking religious freedom. A small number of Catholics and agnostics were also among the colony.

The French and Spanish encounter ended tragically for the French. Despite warnings of a hurricane, Ribault set sail to the newly established Spanish fort at St. Augustine. The hurricane decimated his fleet and left him and his men stranded. Admiral Menendez took advantage of the opportunity and attacked the loosely guarded Fort de la Caroline killing all but 60 women and children. A remnant of 40 or 50 colonists, including Laudonniere, managed to escape the siege and safely set sail to France. Menendez then marched his men south where he found the stranded Ribault and his men. He mercilessly slaughtered Ribault and 350 men, only Catholics and a handful of musicians were spared. The French enacted their revenge under Dominique de Gourges two years later when he and local Native tribes joined forces and massacred Spaniards at three forts, including Fort San Mateo, previously Fort Caroline. De Gourges and his men promptly left Florida after their revenge killings. The French never settled in Florida again.

The role Florida played in the exploration and colonization of North America is often in the backdrop of stories of Plymouth and Roanoke. Spanish and French expeditions through Florida and the Southeast gravely affected Native peoples and resulted in a reshaping of Native American population and culture history in the Southeast. Explore De Soto National Memorial and Fort Caroline National Memorial to learn more about the role Florida played in European expeditions in the New World.

Learn more about De Soto at the parks:

De Soto National Memorial

Fort Caroline National Memorial

Timucuan Ecological & Historic Preserve

Explore De Soto's route:

Georgia and Tennessee (Chickamauga & Chattanooga National Military Park)

South Carolina (Congaree National Park)

National Register Travel Itinerary: The Spanish Claim to Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas, 1513-1821

This article originally appeared on the NPS Museum Collections Blog, courtesy of the NPS Museum Management Program.