Last updated: May 5, 2022

Article

Space is for Everyone

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

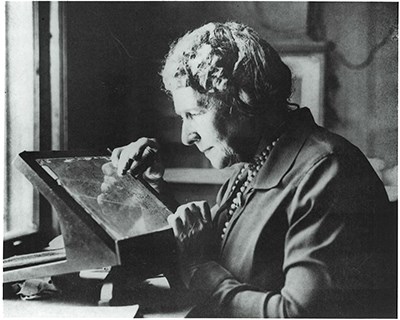

Annie Jump Cannon

Did family influence the career you chose?

The “census taker of the sky” who cataloged more than 350,000 stars and revolutionized the way astronomers classify stars. Her mother Mary ignited her interest in astronomy by stargazing with her through a trapdoor in the roof where they had built a small observatory. Her mother encouraged her to study science and math in college. Annie was later hired to work with the Harvard computers creating the first Henry Draper Catalogue of the stars.

As part of her work at Harvard, Cannon created a stellar classification system based on stellar temperature. This became known as the Harvard spectral classification system and a modified version of it is still used today. Cannon’s system expanded upon and greatly simplified the work of other computers in the group (Williamina Flemming and Antonia Maury). Stars are classified as OBAFGKM by their temperature which correlates with color and a number determined by the star’s absorption spectrum (which indicates composition). Our Sun is a G2 star. In the modern system an additional roman numeral is used to indicate the luminocity or brigtness of the star, our sun is a G2V.

She earned a doctorate in astronomy in 1921 and continued to work in the field for around 40 years. It was thought by some that severe hearing loss from a childhood illness contributed to her ability to focus intently on her classifications.

In addition to her scientific work, Cannon was a strong advocate for women’s voting rights.

NASA Marshall Space Flight Center

Dr. Mae Jemison

What are you driven to achieve?

A medical doctor, chemical engineer, astronaut, multi-lingual teacher, dancer and actress Dr. Jemison is truly a Jill-of-all-trades. She grew up watching the Apollo missions on television, sad that there were no women among the astronaut corps, but Nichelle Nichols (Lt. Uhura on the original Star Trek TV series) inspired her to pursue a career as an astronaut.

She graduate hich school at sixteen and earned a chemical engineering degree from Stanford. There she also danced and choreographed a performing arts production. She earned an M.D. from Cornell University and worked with the peace corps. She is fluent in Russian, Japanese, and Swahili in addition to English and ran her own private medical practice.

At the age of 31 she was selected to be an astronaut in the first group chosen after the Challenger disaster.

After retiring from NASA, Dr. Jemison started a consulting company that encourages science, engineering and social change. She taught at Dartmouth College, appeared in an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, and headed the Jemison Institute for Advancing Technology in Developing Nations--the mission of which is to research, design and evaluate cutting edge technology for the benefit of developing countries. She created a space camp for students ages 12-16 called The Earth We Share, created the Dorothy Jemison Foundation for Excellence non-profit, and wrote an autobiography titled “Find Where the Wind Goes”. She is currently the head of the Hundred Year Starship Project, a group which aims to make interstellar travel capability a reality within the next one hundred years.

Elena Poniatowska/Haciaelespacio.gob.mx

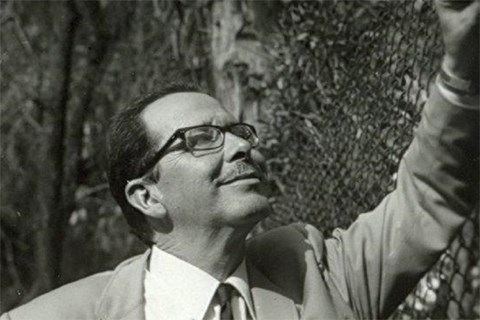

Guillermo Haro

How did you discover your passion?

Guillermo Haro was a philosophy student when he met Luis Enrique Erro, an amateur astronomer, who ignited Haro’s interest in astronomy. After earning his philosophy degree, he began working at the National Astrophysical Observatory of Tonantzintla and later worked at observatories in the USA and collaborated with astronomers around the world becoming one of the central figures of 20th century science in Mexico. He founded the Instituto Nacional de Astrofísica Óptica y Electrónica (INAOE) and the Mexican Academy of Sciences, and was elected the vice-president of both the International Astronomical Union and the American Astronomical Society.

Over the course of his career, Haro discovered nebulae, flare stars, starburst galaxies, several quasars, and a comet. Guillermo Haro and George Herbig concurrently discovered a new class of object now known as Herbig-Haro objects. These objects are formed when gas ejected by young stars collides with gas and dust nearby at high speeds which produces jet-like structures along the rotational axis of the young stars. Herbig-Haro (HH) objects can evolve visibly over relatively short periods of time, providing a beacon to stellar nurseries largely hidden by dense clouds of gas and dust. Many astronomers theorize that these stars may also be surrounded by planet-forming disks.

Perhaps in the coming months NASA’s newest space telescope can peak behind the curtains of HH objects to reveal the secret lives of these newborn stars.

National Media Museum Science & Society Picture Library

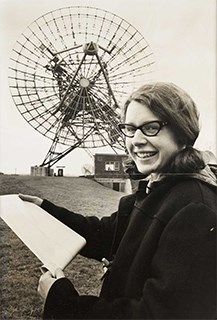

Jocelyn Bell Burnell

Have you ever had a mentor take credit for something you did?

Born into a Quaker family in Northern Ireland in 1943, her parents firmly believed that all children should be taught science and demanded that the school include her in the science classes. She was often met with hostilty and bullying from teachers and male students but was not deterred from her goal of being a radio astronomer.

She applied to and was accepted at Cambridge University in 1967 to study Astrophysics. While the department provided funding and her advisor inspired the project, Burnell built and ran the telescope, analyzed the data, and found two pulsing radio signals, the earliest detections of what we now know as pulsars.

Who would you say discovered pulsars?

Her advisor, Dr. Antony Hewish and the department head Dr. Martin Ryle won the Nobel Prize in 1974 for the discovery of pulsars.

Pulsars, often called the most useful stars in the universe, are neutron stars that emit beams of radio waves outward from the poles of their magnetic fields. When their rotation spins a beam across the Earth, radio telescopes detect that as a “pulse” of radio waves. By precisely measuring the timing of such pulses, astronomers can use pulsars for unique “experiments” at the frontiers of modern physics. Pulsars are particularly useful when studying Gravity and General Relativity.

IAU/M. Zamani

Wanda Diaz Merced

Have you been left out of a group project? How could you have made the project better if you been included?

Born in Puerto Rico, she started to lose her sight as a teenager. Because she couldn’t see well, she wasn’t understanding anything in the classroom. “The transmission of information just was not accessible – I couldn’t see what the lecturers were writing on the board and I didn’t have access to the books”. As her vision worsened, she was forced to make a decision: quit, or keep going. She chose to persevere, she repeated classes until she got her degree. It took her six years.

While doing her bachelor’s degree a friend played her live audio from a solar flare. A huge ejection of energy from the sun that reaches detectors on the ground. It was inspiring. I could hear the sun in real-time, and when the sunburst finished, I could hear the galactic background.

During her internship at NASA Goddard Spaceflight Center she and her mentor created prototype technology to analyze data that had been converted to sound.

She later created ‘sonification’ software that allowed her to participate fully in astrophysical endevors. To test it she asked experienced scientists to simulate a task used to identify black holes near galaxies. The data was presented as sound only, visual only, and sound and visual mixed together. The experiments revealed that sonification of the data improved astronomers’ ability to detect the subtle signals indicating the presence of a black hole. “I felt really disappointed at that moment, because people like me had been completely left out of the field for no reason”.

“Information access empowers us to flourish. It gives us equal opportunities to display our talents and choose what we want to do with our lives, based on interest and not based on potential barriers. When we give people the opportunity to succeed without limits, that will lead to personal fulfillment and prospering life.” -Wanda Diaz Merced

Courtesy Curator of Astronomical Photographs at Harvard College Observatory

Williamina Flemming

How do you balance work and home life?

Born in Scotland in 1878 and having lost her father at age seven, Williamena began student teaching at age 14 to support her mother and siblings. Shortly after she and her husband moved to the U.S he abandoned her and their child. Williamina became a maid in the household of a prominent Harvard astrophysicist, E.C. Pickering, who later made her part of Harvard Observatories staff of “computers” and photograh curators.

Flemming led the team of computers (all women) in cataloging and analyzing photographs taken by the Harvard Astronomers (all men) and classified over 28,000 stellar spectra even developing a new classification system for stars. She wrote, edited and proofread the observatory’s research papaers, annual reports and data tables.

Over the course of her career, she discovered hundreds of new variable stars, 10 novae (stellar explosions) and, 59 nebulae including the iconic Horsehead Nebula in Orion.

NASA Photo

She also advocated for more women to be employed in astronomy, and argued that the women should recieve better wages (they were paid 25 cents an hour, less than half what the men made).

She was an immigrant, a single mother, an advocate for her fellow coworkers, a dedicated scientist, and the first American woman elected to honorary membership in England’s Royal Astronomical Society.