Last updated: August 22, 2024

Article

Wildlife Monitoring at Saguaro National Park's Tucson Mountain District: 2022

Gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus). NPS photo.

Overview

At National Park Service units across the Sonoran Desert and Apache Highlands, the Sonoran Desert Network (SODN) is monitoring medium- and large-sized mammals. The goal of this project, started in 2016, is to detect biologically significant changes in mammal community and population parameters through time. The intent is to provide park managers with reliable, useful information on mammal species at various spatial and temporal scales. To do this, we use passively triggered remote wildlife cameras in concert with methods of sampling and analysis that address management needs.

Key points

- In 2022, field crews deployed 59 wildlife cameras that recorded 10 different mammal species at Saguaro National Park.

- Knowing how wildlife populations change through time, and how different variables impact them, helps managers decide how best to protect species now and into the future.

- Single-year data provide species-specific insights.

In 2022, SODN field crews deployed 59 wildlife cameras at Saguaro National Park’s Tucson Mountain District (TMD). The cameras recorded 2,411 total detections (animal photographs) from January 11 until February 26. Upon analysis, the photos revealed a total of 10 mammal species, plus an additional two mammalian families or genera that could not be identified to species due to insufficient visual evidence. Three bird species were detected, plus an additional 48 birds that could not be identified to species.

Investigating how wildlife populations change through time, and how different variables impact them, gives us valuable insight into how best to manage and protect species now and into the future. While this report only summarizes findings from 2022, those findings will be combined with data collected from past and future years for use in occupancy modeling. Occupancy modeling provides SODN and park managers with multi-year information on the status and trends of mammal species, including their population distribution and stability.

At least five years of pooled data are needed to establish reliable multi-year occupancy models. The methods for multi-year trend analysis are currently in development, as we have just obtained enough data to begin. However, to provide a sense of what can be learned from this modeling, an example of an occupancy model for a single species using only the 2022 data appears below. Single-year data are also useful for other species-specific insights, such as new detections within the monument and potential drivers of species distributions.

Motivation for wildlife monitoring

The need for wide-scale environmental monitoring to meet conservation needs is increasing. In response to anthropogenic disturbances, such as habitat loss and climate change, many species face pressures that force shifts in their distribution. Expansive tracts of suitable habitat to allow for such shifts are a conservation necessity (Parmesan and Yohe 2003, Thomas et al. 2004). Large protected areas, such as national parks, can provide critical wildlife habitat—but even they are not immune to anthropogenic disturbances (Brashares 2010, Carroll 2010, Chen et al. 2022). Knowing how species respond to various pressures requires an understanding of abiotic and multi-species interactions at broad spatial scales. Occupancy modeling of data from remote cameras can help meet this challenge (Post et al. 2009).

Use of cameras

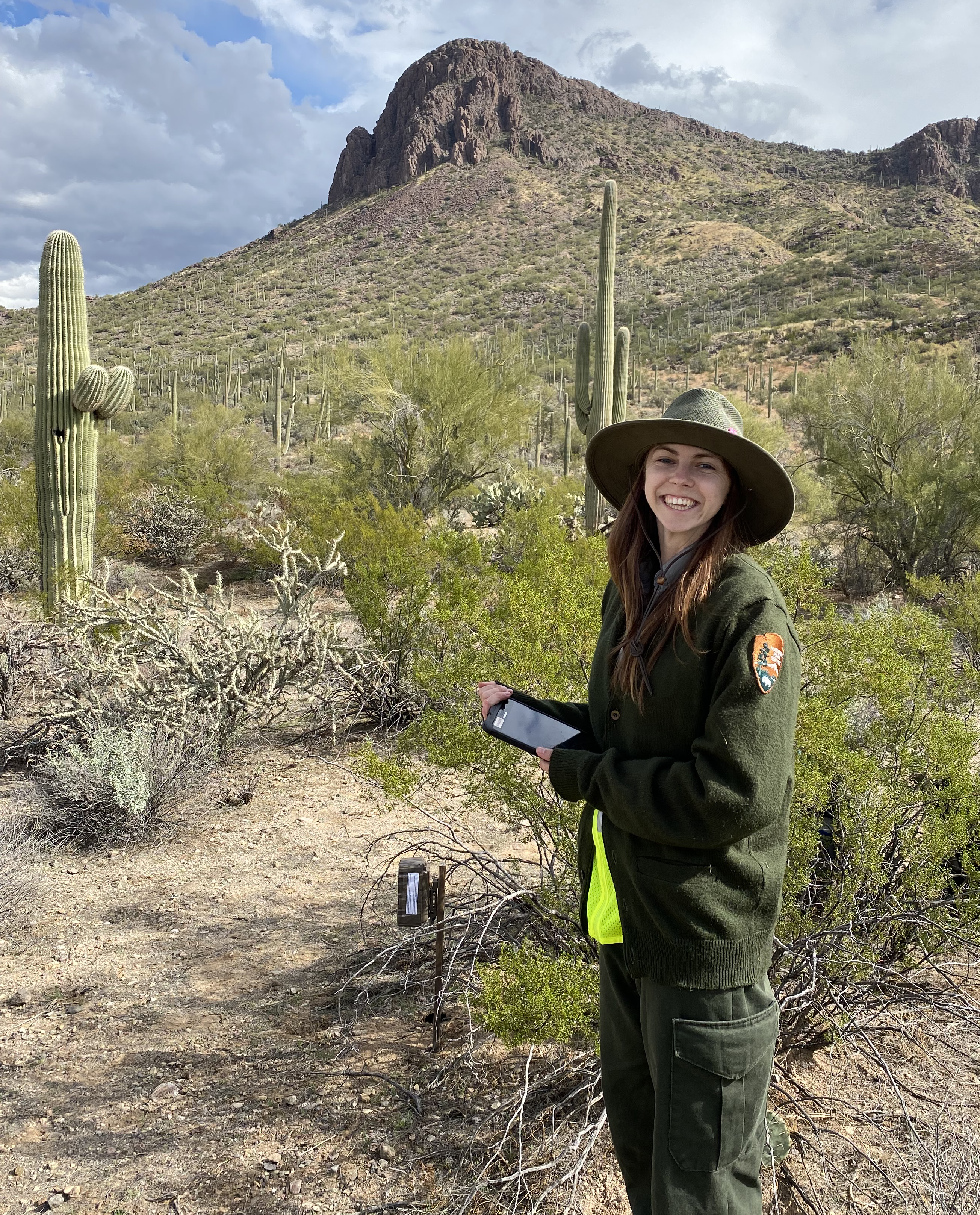

Wildlife camera deployed at Saguaro National Park, Tucson Mountain District.

Remote wildlife cameras are powerful research tools. They are non-invasive and allow researchers to collect data on multiple species simultaneously over large spatial scales. Scientists worldwide have demonstrated the ability of remote cameras to provide robust trend-monitoring data for terrestrial mammals. Remote cameras can capture data on individual animals that are uniquely identifiable, such as jaguars, which enables trend estimations of their broader population through mark-recapture modeling (Steenweg et al. 2015). However, many animals without unique pelage (fur markings and patterns) can only be recognized to the species level, rendering mark-recapture modeling impossible. Instead, occupancy modeling provides a means to monitor distribution (occupancy) trends of numerous species concurrently.

What is occupancy modeling?

In SODN’s monitoring, occupancy is the proportion of an area that is inhabited (occupied) by a species. When a species is detected by a camera, it is classified as present. If a species is not detected by a camera, it may be either truly absent, or present but undetected. This issue of imperfect surveys (i.e., when the probability of detecting a species is less than 1) can be statistically accounted for with occupancy modeling. A rigorous framework for occupancy modeling has existed since 2002 (MacKenzie et al. 2002) and is in strong subsequent development (MacKenzie et al. 2006, 2018). Therefore, we utilize occupancy modeling for the data collected by wildlife cameras at Saguaro National Park’s TMD and other parks.

While the data tell us where a species occurs, they do not tell us why a species does or does not occur at a particular location. We can assess the driving contributors to a species’ distribution by evaluating the effects of covariates on occupancy and detection probability. Some environmental influences, such as elevation, do not change during a sampling window and likely influence occupancy probability. Other environmental variables, such as temperature or precipitation, change day-to-day and may influence detection probability (e.g., species may be harder to see and less active in excessive heat). By including covariates, we can evaluate their influence on wildlife occupancy and detection probability and begin to understand why a species is detected at one place and/or time but not another.

Effort

In January 2022, SODN field crews deployed 59 Cuddeback G Series wildlife cameras at non-baited, pre-established monitoring locations throughout Saguaro National Park’s TMD. The cameras have been deployed during the same time period and in the same locations annually since 2017 (except for 2019 due to the government shutdown). We chose to pair our camera locations with SODN’s long-term vegetation and soil monitoring plots, which were allocated mostly through a Reversed Randomized Quadrant-Recursive Raster (RRQRR) spatially balanced design (Theobald et al. 2007, Hubbard et al. 2012). This pairing will enable us to utilize detailed covariate data on vegetation species composition and structural characteristics that are potentially important drivers of habitat conditions impacting wildlife.

Technicians followed standard operating procedures to ensure the cameras were deployed consistently (Hubbard et al. in prep). For example, the cameras were placed in the same locations and employed the same settings as in prior years. The cameras were either mounted on a stake in the ground or strapped to a secure structure, such as a tree.

Relying on infrared and motion-trigger technology, the cameras took a photo whenever they detected motion or a sudden temperature change in their detection zone. They collected data for a sampling period from January 11 until February 26, 2022, and were then retrieved. Technicians again followed standard operating procedures to ensure the cameras were retrieved consistently (Hubbard et al. in prep), including documenting each camera’s functionality and properly removing and storing their memory cards.

Back at the office, technicians analyzed the contents of the memory cards. This process begins by downloading the photos and sorting them to remove “false triggers,” which are photos that do not contain an animal. A photo that does contain an animal is classified as a “detection.” From there, the dataset is further sorted using the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Photo Warehouse Database, which helps us categorize photos and attribute spatial, temporal, and species metadata to them (Ivan and Newkirk 2016). Finally, a metadata export is produced for use in occupancy analysis.

Single-species single-season occupancy models

Many large-scale wildlife occupancy trend models require data from consecutive years, which renders data from a single sampling period inadequate for trend analysis. However, the terrestrial mammal data we collect from a single field season can still be informative and incorporated into different occupancy models that provide information on specific species or covariates of interest.

As an example, we modeled occupancy using a single-season, single-species approach (MacKenzie et al. 2002, 2006) with package “unmarked” in R (Fiske and Chandler 2011). To minimize heterogeneity caused by short periods of high activity in front of the cameras, we grouped our 2022 detection data into seven-day sampling periods (Bowler et al. 2017, MacKenzie et al. 2018, Kays et al. 2020). We then selected nine target species for analysis based on two criteria: rarity and body size. We deemed terrestrial mammal species reliably detectable and identifiable by cameras if they were at least 43 centimeters long, which is equivalent to the size of a rock squirrel (Spermophilus variegatus). Smaller animals can be difficult to identify correctly through photographs, especially nocturnal animals with similar characteristics. For this reason, we excluded smaller rodents, such as chipmunks, rats, and mice from analysis. Furthermore, we only included species for analysis that were detected at least once on >30% of sampled sites to minimize statistical modeling errors. This excluded rarer species, such as American badger (Taxidea taxus).

Because we had limited initial information about which covariates might influence occupancy and detection probabilities, we chose backwards elimination over an information-theoretic approach (Steidl 2006, 2007) to identify covariates with explanatory power (Ramsey and Schafer 2013). We first identified covariates that influenced detection probability with an intercept-only model, then used those in models for occupancy, retaining only those covariates with some explanatory power (p <0.10).

Field crews deployed 59 wildlife cameras in the TMD during 2022.

Field crews deployed 59 wildlife cameras in the TMD during 2022.Results for 2022

Detections

During the 2022 sampling window (January 11–February 26), 59 wildlife cameras recorded 2,411 total detections (i.e., animal photographs) in the TMD, including 2,339 detections of mammals identified to 10 species and 119 detections identified to family or genus (see table). Several animals, detected 22 times, exhibited clear mammalian characteristics but were unable to be classified further due to insufficient visual evidence. Three bird species were also detected, along with 48 detections of birds that could not be identified to species.

A few notable detections from 2022 included American badger (Taxidea taxus) and domestic dog (Canis familiaris). The detections of American badger were encouraging, because they play an important role ecologically but are generally uncommon or even rare to observe in the TMD. It is also uncommon to capture dogs in the park—but not unheard of, because there are residential areas nearby.

The number of statistically significant wildlife photos (i.e., photos containing an animal) collected from sampling in the TMD has ranged from 1,994 to 4,054 annually. It is hard to know exactly why this range has varied throughout the years. We are hoping to gain insight into this question and others by assessing the impacts of environmental factors on mammal distribution and detectability via occupancy modeling. We currently have five years of data (2017–2022, excluding 2019, due to the government shutdown).

Citizen scientists typically assist with the fieldwork associated with camera deployments and retrievals. In 2022, five volunteers and six interns from various parks and partner organizations helped deploy and retrieve cameras in the TMD. We are grateful for their support.

| Class | Common name | Scientific name | Number of detections |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mammal | Javelina | Pecari tajacu | 836 |

| Mammal | Mule deer | Odocoileus hemionus | 607 |

| Mammal | Black-tailed jackrabbit | Lepus californicus | 198 |

| Mammal | Coyote | Canis latrans | 192 |

| Mammal | Gray fox | Urocyon cinereoargenteus | 180 |

| Mammal | Desert cottontail | Sylvilagus audubonii | 124 |

| Mammal | Bobcat | Lynx rufus | 48 |

| Mammal | Domestic dog | Canis familiaris | 9 |

| Mammal | American badger | Taxidea taxus | 3 |

| Mammal | Harris’s antelope squirrel | Ammospermophilus harrisii | 1 |

| Mammal | Unknown jackrabbit | Lepus sp. | 118 |

| Mammal | Unknown skunk | Mephitidae | 1 |

| Mammal | Unknown mammal | Mammalia | 22 |

| Total mammals | -- | -- | 2,339 |

| Bird | Greater roadrunner | Geococcyx californianus | 15 |

| Bird | Gambel’s quail | Callipepla gambelii | 7 |

| Bird | Curve-billed thrasher | Toxostoma curvirostre | 2 |

| Bird | unknown bird | Aves | 48 |

| Total non-mammals | -- | -- | 72 |

| Total | -- | -- | 2,411 |

Why is this Information Useful?

Long-term monitoring allows us to evaluate trends in parameters of management interest. Modeling occupancy over several years provides SODN and park managers with information on the status and trends of mammal species, including their population distribution and stability. Occupancy is often used as a surrogate for abundance (MacKenzie et al. 2018), so pooling annual occupancy estimates can help us determine how stable or unstable a wildlife population is. When analyzed with occupancy models, SODN’s photographic dataset enables us to monitor trends of numerous terrestrial mammal species, including whether they are potentially increasing, stable, or decreasing.

Depending on the covariates used in the modeling process, we can also plot trends of covariate influence on wildlife occupancy and detection probabilities. For example, assessing the influence of temperature and precipitation on wildlife occupancy and detection is helpful when we want to understand the potential impacts of climate change on species or populations of interest.

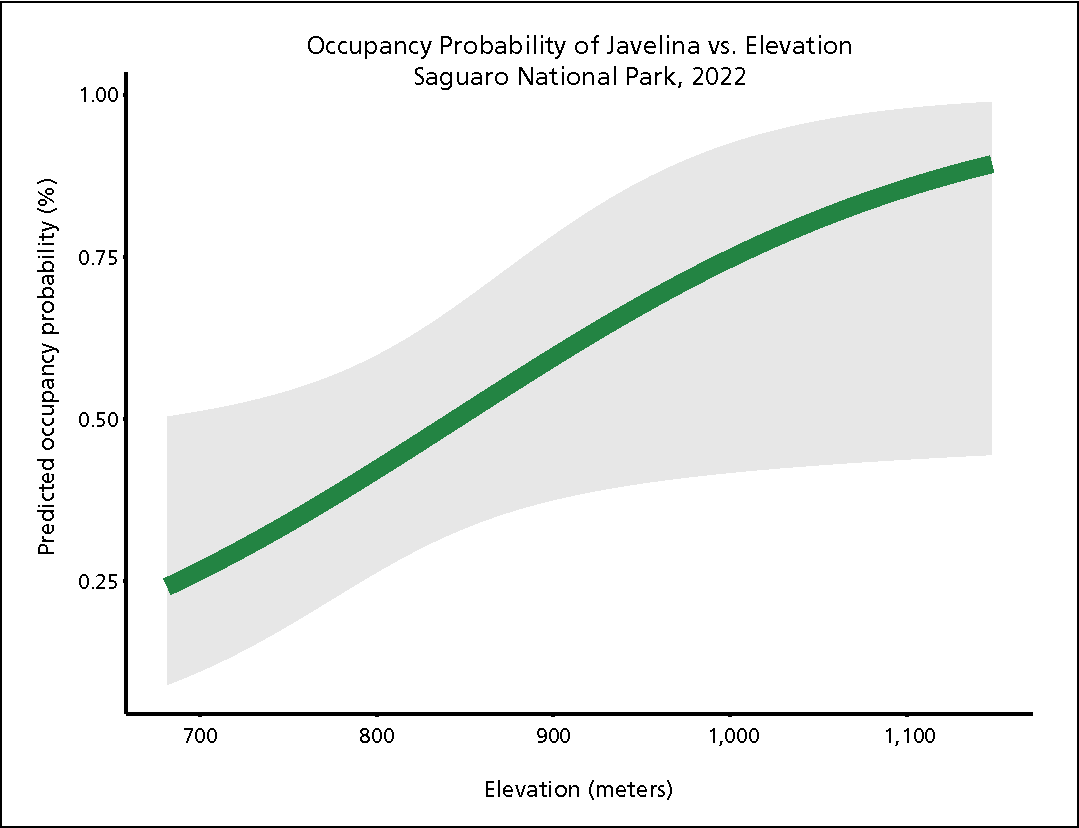

Single-season, single species analysis example

Below is an output of a single-season, single-species occupancy model for javelina (Pecari tajacu) in Saguaro National Park’s Tucson Mountain District, based on data collected in 2022. This model illustrates the influence of elevation on the occupancy probability of javelina. More specifically, the model shows a positive relationship between these two parameters, with the occupancy of javelina increasing as elevation increases. In the TMD’s lower-elevation areas, occupancy probability of javelina is low (25–50% occupied). However, the occupancy probability of javelina rises significantly (more than 75%) in high-elevation areas (above 1,050 meters elevation).

The model suggests javelina prefer to inhabit higher-elevation areas over lower-elevation areas in the TMD. While more research is needed to understand why javelina exhibit this preference, it may be that higher-elevation areas provide cooler, more secluded habitat than the TMD’s lower-elevation areas, which are hotter and experience more disturbance from roads, hiking trails, and humans. This model provides park managers with insight into how javelinas utilize different areas of the park. It also illustrates how data from a single sampling period can provide valuable information.

Occupancy probability of javelina in response to elevation at Saguaro National Park’s Tucson Mountain District in 2022. Occupancy probability increases with increasing elevation within the park. The average is illustrated in green and the standard error is illustrated in grey.

Brashares, J. S. 2010. Filtering wildlife. Science 329:402.

Bowler, M. T., M. W. Tobler, B. A. Endress, M. P. Gilmore, and M. J. Anderson. 2017. Estimating mammalian species richness and occupancy in tropical forest canopies with arboreal camera traps. Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation 3:146–157.

Carroll, C. 2010. Role of climatic niche models in focal-species-based conservation planning: Assessing potential effects of climate change on Northern Spotted Owl in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Biological Conservation 143:1432–1437.

Chen, C., and others. 2022. Global camera trap synthesis highlights the importance of protected areas in maintaining mammal diversity. Conservation Letters 15(2).

Fiske, I., and R. Chandler. 2011. unmarked - an R package for fitting hierarchical models of wildlife occurrence and abundance. Journal of Statistical Software 43:1–23.

Hubbard, J. A., C. L. McIntyre, S. E. Studd, T. Naumann, D. Angell, K. Beaupre, B. Vance, and M. K. Connor. 2012. Terrestrial vegetation and soils monitoring protocol and standard operating procedures: Sonoran Desert and Chihuahuan Desert networks, version 1.1. Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR—2012/509, National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Hubbard, J. A., E. C. Dillingham, and A. Buckisch. In prep. Terrestrial mammal monitoring protocol implementation plan for the Sonoran Desert Network.

Ivan, J. S., and E. S. Newkirk. 2016. CPW Photo Warehouse: A custom database to facilitate archiving, identifying, summarizing and managing photodata collected from camera traps. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 7:499–504.

Kays, R., B. S. Arbogast, M. Baker‐Whatton, C. Beirne, H. M. Boone, M. Bowler, S. F. Burneo, M. V. Cove, P. Ding, S. Espinosa, A. L. S. Gonçalves, C. P. Hansen, P. A. Jansen, J. M. Kolowski, T. W. Knowles, M. G. M. Lima, J. Millspaugh, W. J. McShea, K. Pacifici, A. W. Parsons, B. S. Pease, F. Rovero, F. Santos, S. G. Schuttler, D. Sheil, X. Si, M. Snider, and W. R. Spironello. 2020. An empirical evaluation of camera trap study design: How many, how long and when? Methods in Ecology and Evolution 11:700–713.

MacKenzie, D. I., J. D. Nichols, G. B. Lachman, S. Droege, J. Andrew Royle, and C. A. Langtimm. 2002. Estimating site occupancy rates when detection probabilities are less than one. Ecology 83:2248–2255.

MacKenzie, D. I., J. D. Nichols, J. Royle, K. Pollock, L. Bailey, and J. Hines. 2006. Occupancy estimation and modeling: Inferring patterns and dynamics of species occurrence. Boston, Ma.: Elsevier.

——. 2018. Occupancy estimation and modeling: inferring patterns and dynamics of species occurrence. Second edition. London, UK: Elsevier.

Parmesan, C., and G. Yohe. 2003. A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature 421:37–42.

Post, E., J. Brodie, M. Hebblewhite, A. D. Anders, J. A. K. Maier, and C. C. Wilmers. 2009. Global population dynamics and hot spots of response to climate change. Bioscience 59:489–497.

Ramsey, F. L., and D. W. Schafer. 2013. The statistical sleuth: A course in methods of data analysis. Third edition. Boston, Ma.: Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning.

Steenweg, R., J. Whittington, and M. Hebblewhite. 2015. Canadian Rockies Remote Camera Multi-Species Occupancy Project: Examining trends in carnivore populations and their prey using remote cameras in Banff, Jasper, Kootenay, Yoho and Waterton Lakes National Parks. Final Report. University of Montana. 88p.

Steidl, R. J. 2006. Model selection, hypothesis testing, and risks of condemning analytical tools. Journal of Wildlife Management 70:1497–1498.

——. 2007. Limits of data analysis in scientific inference: Reply to Sleep et al., Journal of Wildlife Management 71:2122.

Theobald, D. M., D. L. Stevens, D. White, N. S. Urquhart, A. R. Olsen, and J. B. Norman. 2007. Using GIS to generate spatially balanced random survey designs for natural resource applications. Environmental Management 40:134–146.

Thomas, C. D., A. Cameron, R. E. Green, M. Bakkenes, L. J. Beaumont, Y. C. Collingham, B. F. N. Erasmus, M. F. de Siqueira, A. Grainger, L. Hannah, L. Hughes, B. Huntley, A. S. van Jaarsveld, G. F. Midgley, L. Miles, M. A. Ortega-Huerta, A. T. Peterson, O. L. Phillips, and S. E. Williams. 2004. Extinction risk from climate change. Nature 427:145–148.

Past Findings

Wildlife Monitoring at Saguaro National Park's Tucson Mountain District, 2021

This report was prepared by Elise Dillingham and Alex Buckisch, Sonoran Desert Network.