Last updated: August 25, 2025

Article

Volunteers Remove Invasive Cape Ivy to Help Restore Bolinas Lagoon Watershed

NPS / Justin Jang

August 2025 - As part of restoring the Bolinas Lagoon watershed, the Watershed Stewards Program, San Francisco Bay Area Inventory & Monitoring Network, Point Reyes National Seashore, and Audubon Canyon Ranch partnered for a volunteer event at Volunteer Canyon Creek. With over a dozen volunteers we removed hundreds of pounds of invasive Cape ivy from the banks of the creek, a sensitive tributary of Bolinas Lagoon.

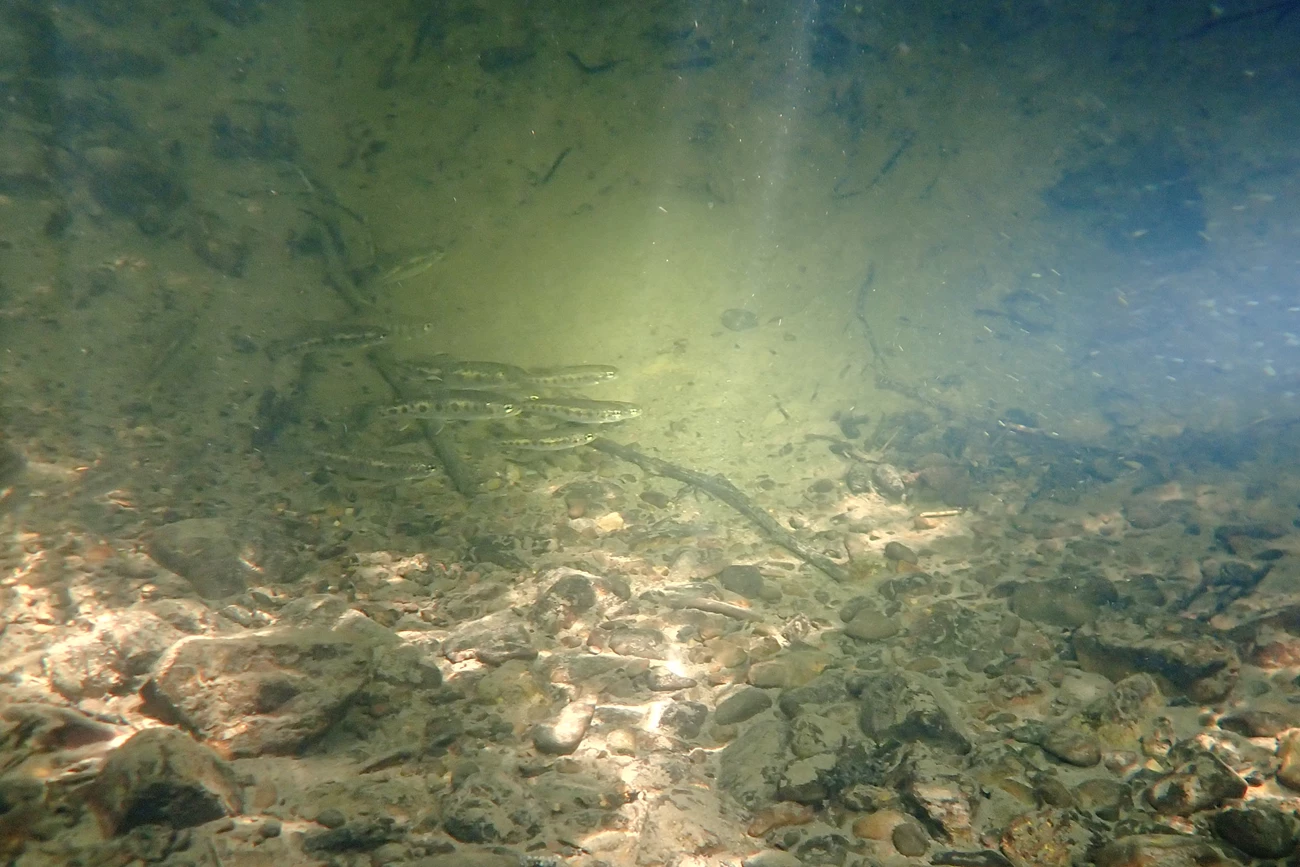

Bolinas Lagoon, a Wetland of International Importance, supports large numbers of harbor seals and migratory birds, and has served as the heart of surrounding communities for thousands of years. It also connects the salmon-bearing Pine Gulch Creek with the ocean. In fact, the impetus for restoring a tributary of the Lagoon came from the recently recovering salmon run on Pine Gulch Creek.

After years of extirpation, coho salmon have returned to Pine Gulch Creek in greater numbers in the last five years. Along with the winter of 2021-22, this past winter of 2024-2025 marked the most successful return in at least 20 years. This points to the possibility of salmonids recolonizing other streams feeding the Lagoon. Bolinas Lagoon has over a dozen streams flowing into it, mostly on the eastern side, such as Volunteer Canyon Creek.

NPS

Cape ivy (Delairea odorata) is a fast-growing vine native to South Africa. It was introduced to California in the 1950s as a common house plant. However, it fell out of popularity because of its ability to grow rapidly yet difficult to eradicate from gardens once planted. On the West Coast, it successfully invaded disturbed areas that contained year-round moisture. For example, from 1987 to 1997, the Cape ivy coverage expanded in the Marin Headlands by over 700%. It is able to reproduce from stem fragments as small as 0.5 inches, which are easily spread through waterways, wildlife, and humans.

Where it takes root outside of South Africa, Cape ivy is uniquely harmful in many ways. It’s able to form dense mats that block out light and smother native vegetation. It also has a shallow root system, contributing to soil erosion on hillsides and impacting flood control functions along streams. On top of that, Cape ivy produces strong chemical compounds (pyrrolizidine alkaloids and xanthones) which are toxic to mammals, spiders, and aquatic macroinvertebrates, and may also decrease fish survival.

NPS / Justin Jang

NPS / Aiko Goldston

The volunteers removed hundreds of pounds of Cape ivy from the banks of Volunteer Canyon Creek, making room for native stream-side species to thrive. On several occasions we pulled down large clumps of Cape ivy only to discover a bent coffeeberry bush, alder sapling, or other native species at the center. Now these formerly-choked riparian plants have the chance to regrow, stabilize sediment, and provide wildlife with food and habitat for years to come. And perhaps these habitat improvements will help adventurous salmon and steelhead to eventually recolonize the creek.

The Watershed Stewards Program holds two restoration events each year between January and July. Learn more by emailing Brentely McNeill at brentely_mcneill@partner.nps.gov. Some events involve planting native trees and shrubs, while others involve removing invasive species. All are focused on restoring local watersheds for salmonids.

For more information

- San Francisco Bay Area Network Salmonid Monitoring webpage

- Pacific Coast Science & Learning Center Coho & Steelhead webpage

- Contact Fishery Biologist Michael Reichmuth

See more from the Bay Area Nature & Science Blog