Last updated: July 8, 2025

Article

Four Birds from Golden Gate and Yosemite Star in New Study of Migratory Species’ Responses to Climate Change

By Science Communication Specialist Jessica Weinberg McClosky, San Francisco Bay Area Network Science Communication Team

© Garth Harwood / Photo 32552464 / 2016-04 / iNaturalist.org / CC BY

August 2022 - Scientists have abundant data on bird population trends and on climate change impacts to habitats around the world. For birds that stay in one place year round, linking the two to study bird population responses to climate change is relatively straightforward. But migratory birds….migrate. Every year they rely on multiple habitats in different parts of the world at different times. As a result, all of that existing data isn’t enough to tease apart how climate impacts birds at different stages of their annual journeys—or to inform more effective conservation strategies. So researchers at The Institute for Bird Populations, Point Blue Conservation Science, and the National Park Service designed a new study. By combining new and existing data, they set out to find answers for two black-headed grosbeak populations in California.

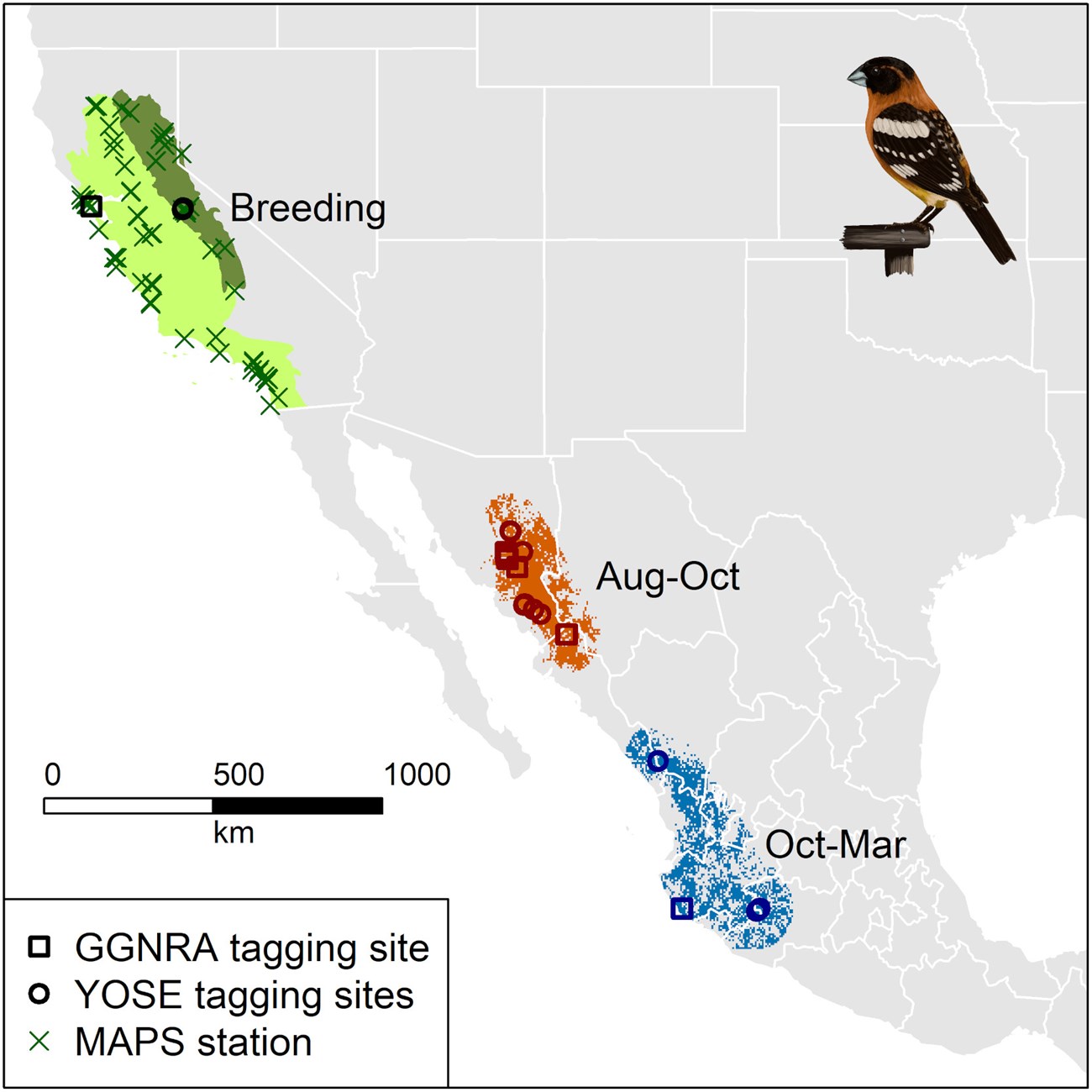

One population breeds in Coastal California and the other in the Sierra Nevada mountain range. But their migration routes, pit stops, and overwintering ranges weren't well documented. Thus before they could proceed, the researchers needed to fill in those gaps. They turned to improvements in tracking technology in the form of GPS tags weighing just under 2g. Team-members tagged 33 grosbeaks captured at MAPS banding stations and other riparian study sites in Yosemite National Park, Point Reyes National Seashore, and Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Such lightweight tags do not actively transmit points, though. The researchers needed to get them back. Luckily, the team recaptured four of the birds during subsequent banding seasons and recovered their tags.

The four birds—one recaptured in Golden Gate and three in Yosemite—provided the researchers with a treasure trove. GPS points recorded every 4-40 days showed that, in August, all the birds migrated to northwestern Mexico to molt. Not all migratory species undertake such ‘molt migrations’, but molting habitat, wherever it is, is crucial for birds. It must feed and shelter them when they are highly vulnerable—due to missing feathers—to things like predators and extreme weather. Then in November, the four grosbeaks proceeded to western Mexico for the winter. Combining the GPS points with vegetation cover maps, the researchers’ outlined the birds’ molting and wintering range extents.

Saracco, J. F., et. al. / Artwork by L. Helton. / CC BY 4.0

From there, the researchers could characterize drought conditions over the years for each of the birds’ ranges. They modeled the relationships between those conditions and vegetation growth timing and greenness. Finally, they created a new population model linking all that climate and vegetation data with black-headed grosbeak demographic data (e.g., age, survival, breeding success) collected from banding stations throughout the birds’ breeding range.

The model revealed stable grosbeak populations from 1992 to 2019. Despite clear climate impacts to their habitats, the birds were minimally influenced by most climate variables. But some climate-population relationships did emerge. For example, the number of breeding adults in the Coastal California population grew most when rains on the birds’ molting grounds came early, and when their winter range was cool and wet.

The researchers suggest that there’s lots of potential to leverage similar methods—and more existing infrastructure and data sets, like banding stations and eBird—to get similarly specific about when and where other migratory species may be most vulnerable to climate change. Ultimately, such targeted findings can help take migratory bird conservation to a whole new level.

For more information

- Saracco, J. F., Cormier, R. L., Humple, D. L., Stock, S., Taylor, R., & Siegel, R. B. (2022). Demographic responses to climate-driven variation in habitat quality across the annual cycle of a migratory bird species. Ecology and Evolution, 12, e8934. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.8934

- Pacific Coast Science & Learning Center Landbirds webpage

- Yosemite National Park: Birds

- San Francisco Bay Area Network Landbird Monitoring

- Sierra Nevada Inventory & Monitoring Network Bird Monitoring

Tags

- golden gate national recreation area

- point reyes national seashore

- yosemite national park

- sfan

- pcslc

- blog

- san francisco bay area

- marin county

- sierra nevada

- california

- mexico

- landbirds

- birds

- migratory birds

- black-headed grosbeak

- migration

- molting

- breeding season

- overwintering

- habitat

- climate change

- climate change impacts

- climate change research

- science

- research

- monitoring

- population modeling

- population dynamics

- literature review

- point blue