Last updated: August 14, 2024

Article

The Section 106 Slow-Down: Diagnosing and Averting Harm to Cultural Resources at Valley Forge

This act established the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, directed states to establish State Historic Preservation Offices, and created the National Register of Historic Places. Together these institutions combine the expertise of members of both public and private sectors, the National Park Service, and state-level officers to formalize the protection of historic and archeological resources. In doing so, they advance public awareness of the buildings, landscape, objects, and intangible identities and values that continue to shape the United States’ national narrative. An essential component of this legislation is the Section 106 review process.

Section 106 requires all federal agencies—or those using federal funds—to determine whether their work would harm historically or archeologically significant resources. If so, agencies have the responsibility to avoid or minimize that harm.

Valley Forge National Historical Park exemplifies the benefits of the Section 106 review process. The park has conducted archeological investigations prior to renovations, installations, and even additions to the natural landscape. These efforts have disclosed thousands of previously unknown precontact and historic artifacts, evaluated sites’ integrity, and authorized—and sometimes revised—construction activities in the interest of protecting the past for the appreciation of the future.

Preparing for a New Park Entranceway

Designs for improving vehicle and pedestrian circulation within Valley Forge National Historical Park in the early 2000s included a new proposed gateway entrance. To assess the potential effects of such improvements on historic and archeological resources, a smaller research area was defined within the overall entranceway area. Grass and trees covered most of the project area.

The steep terrain taken with previous development in the area boded a low potential for intact precontact resources, though archeologists expected remains from Port Kennedy Village, a lightly industrial village that dwindled in the 1900s, and the Continental Army’s encampment from the winter of 1777 to June 1778. Fieldwork in 2005 implemented a shovel test survey, a metal detector survey, and a ground penetrating radar (GPR) survey in six discontinuous sections within the project area.

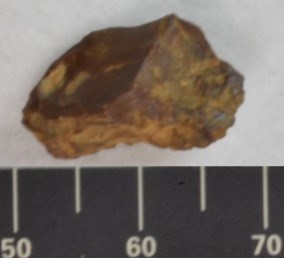

Over 4,000 artifacts were found within 829 shovel tests. Precontact artifacts included 33 flakes, one tested but mostly unmodified cobble, and two adzes. Most of the collected artifacts point to the Port Kennedy period, including five jewelry beads, four plastic comb fragments, 88 sherds of terra-cotta flower pots, and two food wrappers.

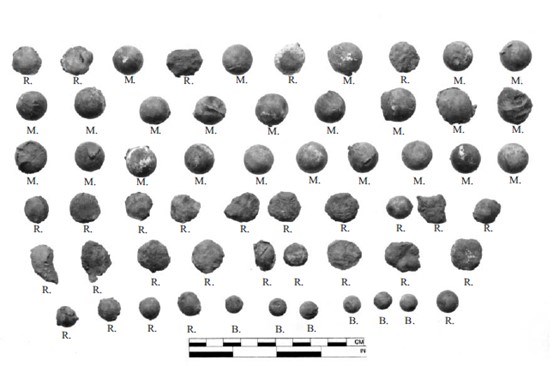

The metal detector survey returned 272 broadly distributed artifacts. A concentration of many squashed or badly misshapen musket balls, rifle balls, and buckshot is indicative of a firing or musketry range used by Continental soldiers during their six-month stay. Their overall distribution follows a generally north-south line—the trainees’ target line. Analysis of the calculated diameters of bullets tells of at least 13 different types of muskets and rifles that soldiers used. The abundance of fired bullets of rifle caliber is unusual in Valley Forge and illuminates the specialized training some of the troops underwent. These conditions qualified the site to join the National Register of Historic Places.

Through seemingly routine projects like approving a new entranceway, adhering to the Section 106 review process reaffirms the merits of each and every archeological site, even those that no longer possess integrity, and encourages the growth of the National Register of Historic Places.

Compliance Begets Precontact Clues

Many projects initiated under Section 106 shift the path of construction activities or impart no effect on them at all, but they guide historical preservation all the same.In the summer of 2021, the park initiated the installation of a new septic system at the Colonial Revival-style Knox-Tindle house. The property belonged to Philander Chase Knox and his family throughout his two terms as US Attorney General and his later position as Secretary of State. No archeological investigations had been conducted in this area before.

Twenty of the test pits yielded a total of 186 historic artifacts. About half of those imply kitchen-related activities, including glass bottle sherds, two animal bone fragments, and seven oyster shell fragments. A recovered wire nail is consistent with the construction of the Knox-Tindle house in 1910. However, a plain pearlware sherd and a blue transfer-printed pearlware sherd date earlier than the house, even though there are no documented prior buildings or structures in the immediate area. The most likely explanation is that occupants of the Knox-Tindle house used the ceramics long after their period of manufacture. Alternatively, neighboring historic farmsteads may have used and discarded the ceramics.

The Spirit of Section 106

Archeology is not just the study of the past; it is the preparation for the future. Only through collective responsibility for both documented and unknown archeological materials alike will our national narrative stand strong.

Archeological undertakings at Valley Forge National Historical Park in advance of laying roads, upgrading utilities, planting trees, and related activities affirm the gravity of Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. By preventing damage to historical and archeological resources rather than merely diagnosing it after it occurs, Section 106 ensures that preservation comes before curiosity. Under the purview of Section 106, even the most unassuming projects become the groundwork for nuanced interpretation, and even the scantest data staves off irrevocable loss.

Resources

Historic Sites Act of 1935. National Park Service.

National Historic Preservation Act. National Park Service.

Siegel, Peter E., et al. Associates Inc. Phase I and II Archeological Investigations for the Proposed Gateway Entrance to Valley Forge National Historical Park, S.R. 0422, Section Src. Prepared for Boles, Smyth Associates, Inc. and Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, 2006.

Turck, John A and Dhillon R. Tisdale. Phase 1 Archeological Investigations for a Septic System at the Knox-Tindle Site (36CH1086), 2021. National Park Service, 2022.