Last updated: August 22, 2024

Article

Habitat and molt strategy shape responses of breeding bird densities to climate variation across an elevational gradient in Southwestern national parks

Doug Greenberg (CC BY-NC)

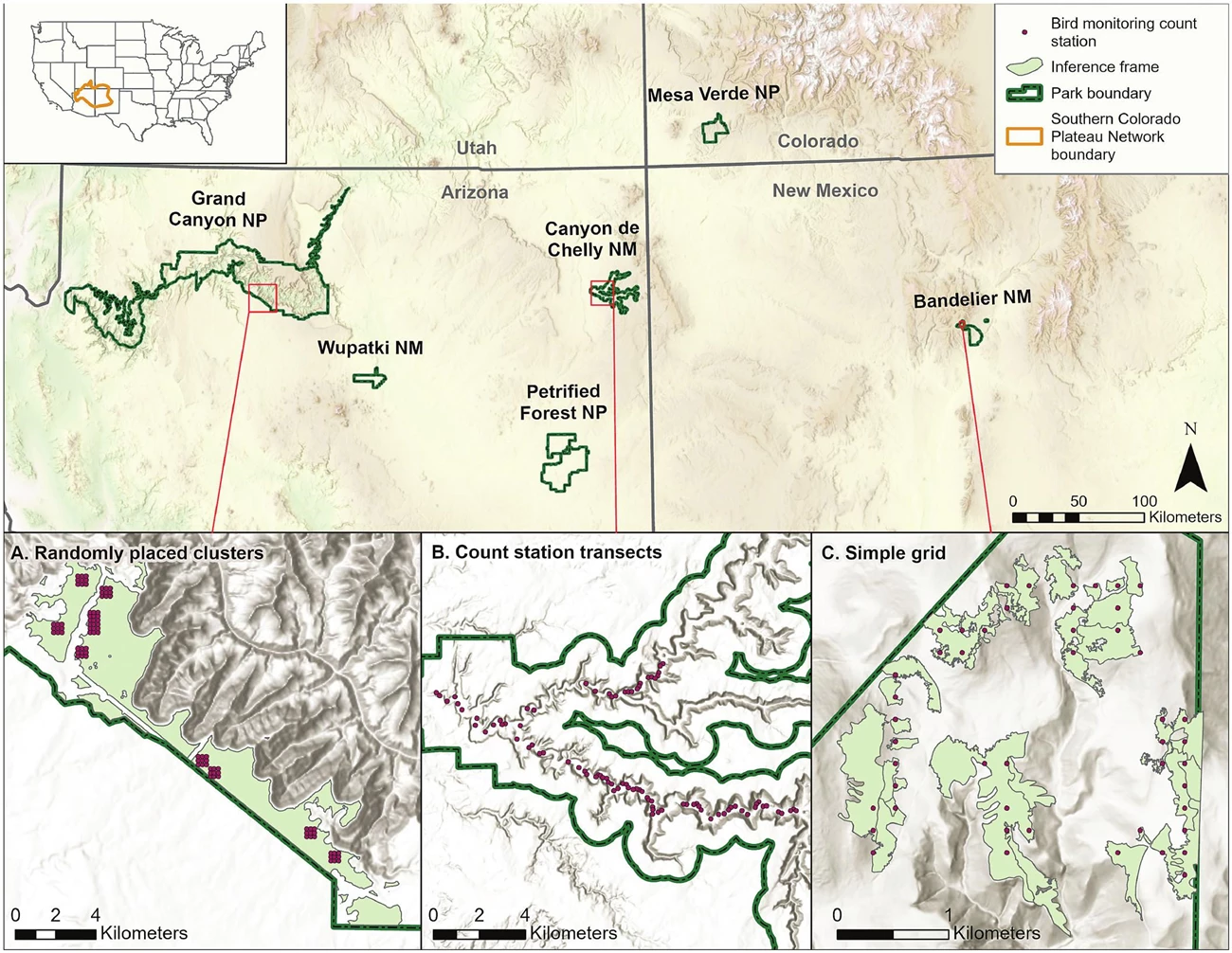

Figure 1. Locations and spatial sampling designs in six Southern Colorado Plateau Network national parks. Monitored parks are bounded in dark green and labeled. Filled polygons in panels (A) and (C) represent the sampling frame (i.e., area of inference for the habitat type selected for monitoring) in three parks and represent the variation in sampling designs across parks. See Methods for sampling frame in Canyon de Chelly NM. Points represent individual count stations, which were arrayed as randomly placed clusters (A), linear transects (B), or simple grids (C) in each park.

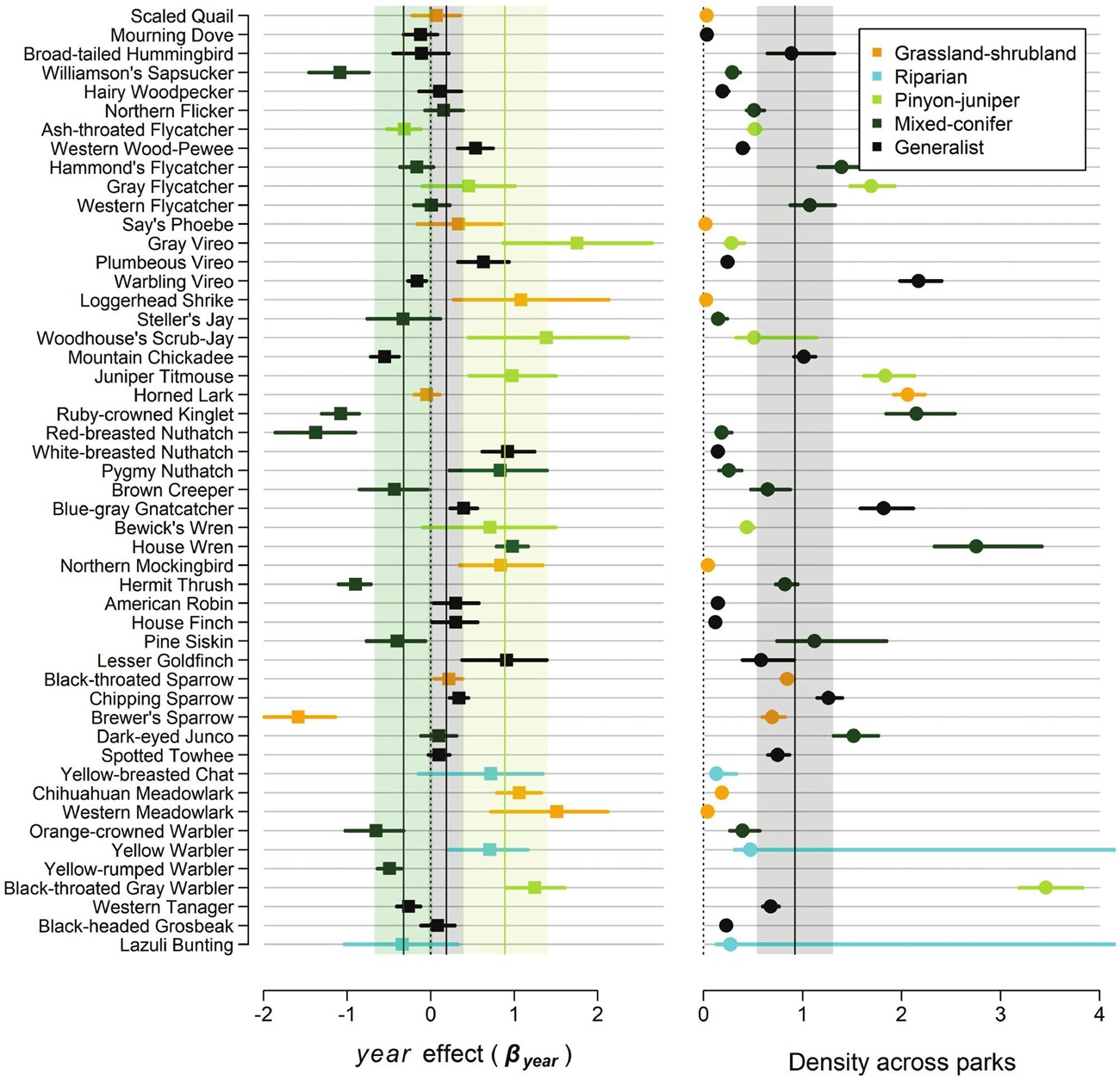

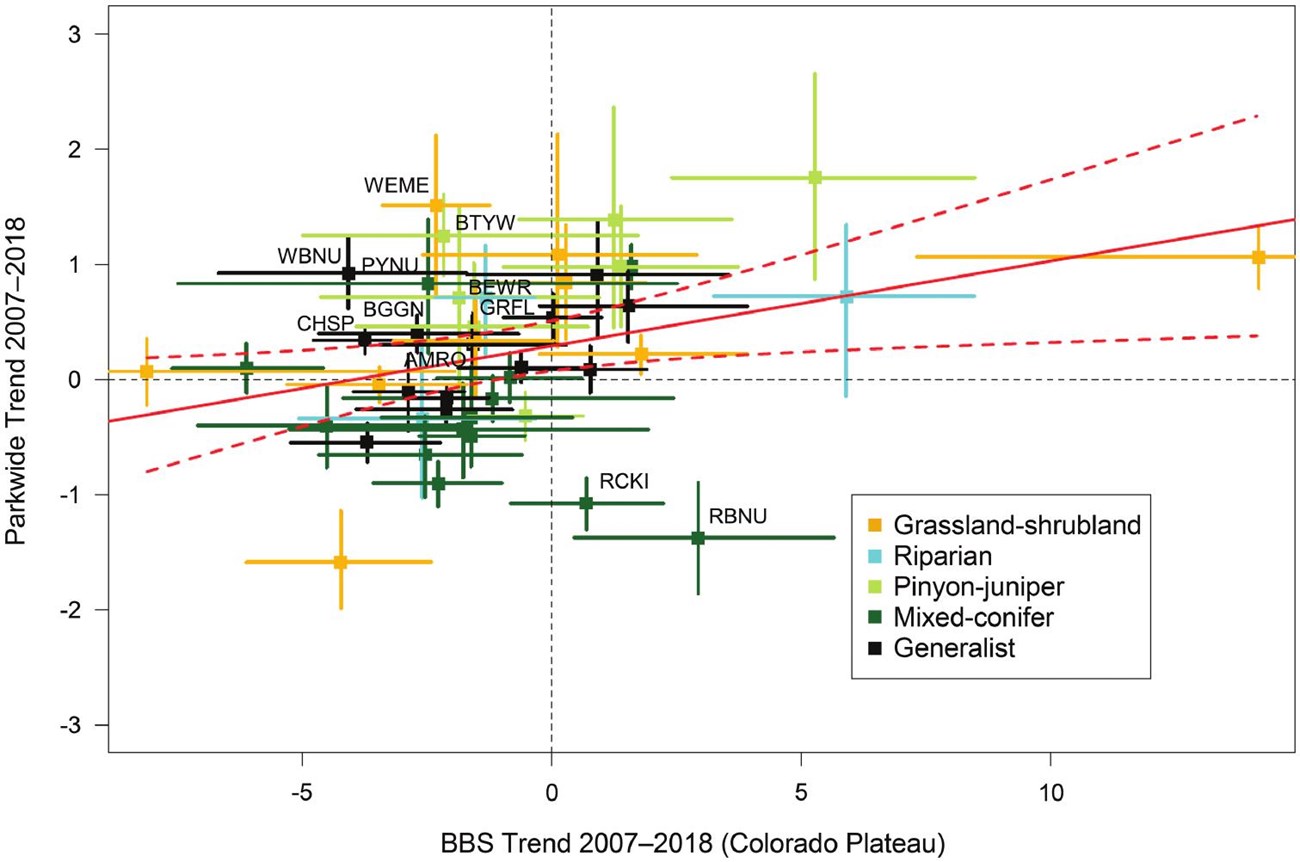

Jones et al (2024) analyzed the densities of 50 bird species in Bandelier NM, Canyon de Chelly NM, Grand Canyon NP, Mesa Verde NP, Petrified Forest NP, and Wupatki NM in relation to spring and summer drought and the timing of North American monsoon rainfall, an important regional pulse of precipitation between July and September. To better understand how climate effects vary by habitat, they used bird population monitoring data from four habitats, including grassland-shrublands, pinyon-juniper woodlands, riparian woodlands, and mixed-conifer forest, that represent a ~1,500 m elevational gradient.

Jones et al (2024) analyzed the densities of 50 bird species in Bandelier NM, Canyon de Chelly NM, Grand Canyon NP, Mesa Verde NP, Petrified Forest NP, and Wupatki NM in relation to spring and summer drought and the timing of North American monsoon rainfall, an important regional pulse of precipitation between July and September. To better understand how climate effects vary by habitat, they used bird population monitoring data from four habitats, including grassland-shrublands, pinyon-juniper woodlands, riparian woodlands, and mixed-conifer forest, that represent a ~1,500 m elevational gradient.

NPS

Ken Lund (CC BY-SA)

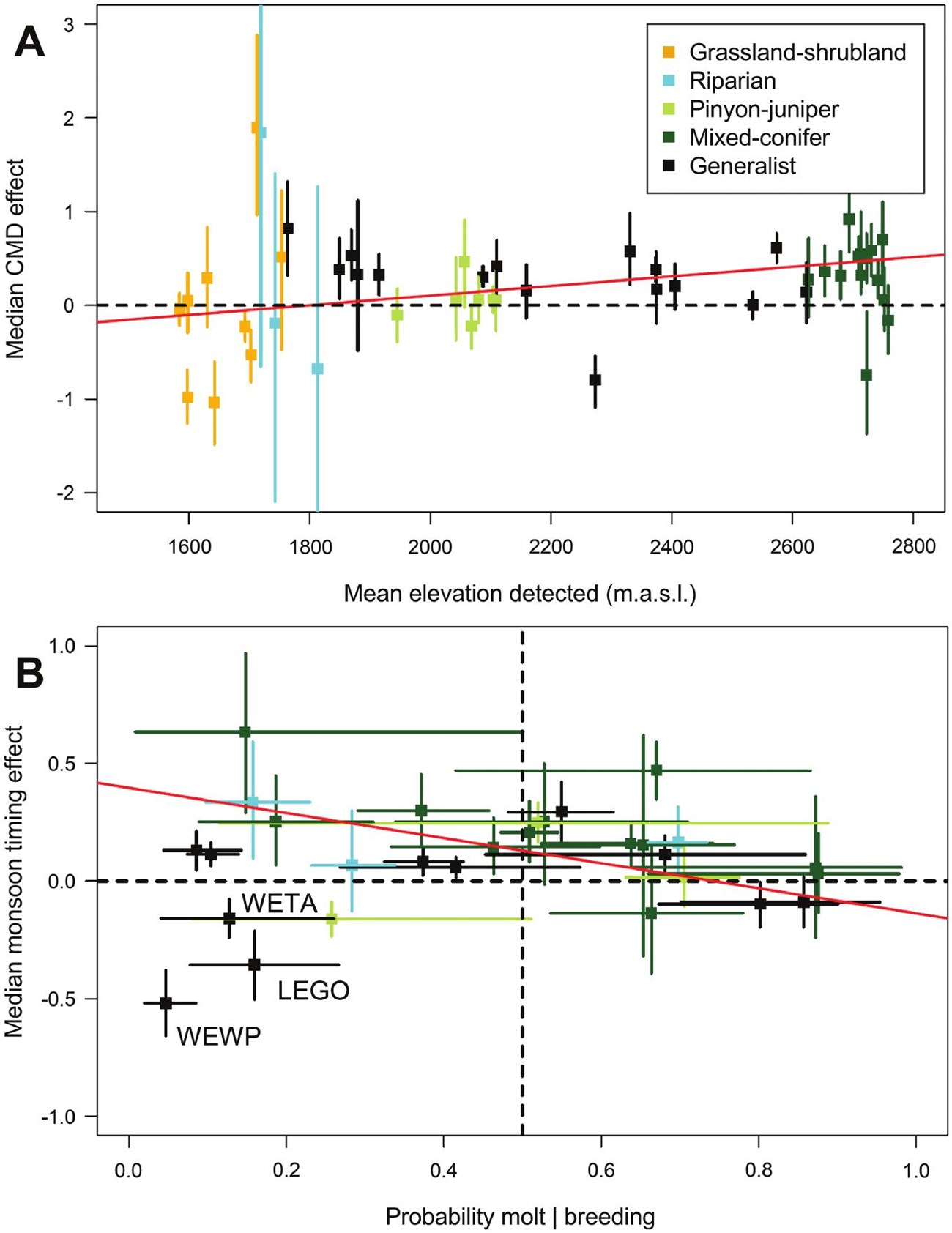

The study also sought to understand how breeding-season densities were affected by drought. Low precipitation paired with above-average temperatures are predicted to be an increasing climatic fixture in the Southwest, which is currently in the midst of a 20-year megadrought. The paper found that drought effects (quantified as the Climatic Moisture Deficit) varied considerably by habitat, with increasingly positive effects for birds breeding in habitats that occur at higher elevations (Figure 4A). Mixed-conifer forest species benefited from drought, likely due to earlier snowmelt and breeding phenology, while middle-elevation pinyon-juniper species were unaffected and grassland-shrubland species at the lowest elevations were negatively affected, perhaps due to reduced nest survival.

Roy Luck (CC BY)

Scott Somershoe/USFWS

A key finding of the work is that climate is already affecting the population dynamics of birds within Southwestern national parks, though responses to both drought and the timing of the monsoon are highly variable across habitats. Habitat-specific studies of climate effects on birds are likely to be most informative for managers, as neither drought nor rainfall timing showed universal effects on breeding densities. Alarmingly, the work also suggests that mixed-conifer forest species at the southern, “warm edge” limits of their breeding ranges are declining, and a better understanding of how drought and wildfire affect habitat suitability for these species is urgently needed. Predictive modelling of climate effects on wildlife populations is increasingly necessary to inform management, particularly as the Southwestern climate continues to diverge from its historical baseline.

NPS

Printable Brief for Grassland-Shrubland Habitat (Petrified Forest National Park and Wupatki National Monument)

Printable Brief for Mixed-Conifer Habitat (Bandelier National Monument, Grand Canyon National Park-North Rim)

Printable Brief for Pinyon-Juniper Habitat (Grand Canyon National Park-South Rim, Mesa Verde National Park)

Printable Brief for Riparian Habitat (Canyon de Chelly National Monument)

Full citation of article: Jones, H. H., C. Ray, M. Johnson, and R. Siegel (2024). Breeding birds of high-elevation mixed-conifer forests have declined in national parks of the southwestern U.S. while lower-elevation species have increased, with responses to drought varying by habitat. Ornithological Applications 126:duae007

Figures reprinted by permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Ornithological Society.

Printable Brief of this web article

Prepared by Christopher Calvo - Southern Colorado Plateau Network

Tags

- bandelier national monument

- canyon de chelly national monument

- grand canyon national park

- mesa verde national park

- petrified forest national park

- wupatki national monument

- birds

- habitat

- climate change

- scpn

- pinyon-juniper woodlands

- riparian habitat

- mixed-conifer habitat

- grassland

- shrubland

- monsoon

- molting

- breeding bird

- science brief

- research

- science