Last updated: January 27, 2022

Article

Scientist Profile: Eric Dinger, Aquatic Ecologist

Eric Dinger

Eric Dinger is happiest at high elevation in the mountains, whether he’s bagging a peak or training field crews to sample high mountain lake water. As the Aquatic Ecologist for the Klamath Inventory and Monitoring Network in southern Oregon, he’s found a way to connect his career with his passions. He leads the monitoring of water quality and aquatic communities in streams and lakes for the network, which includes two high elevation parks: Crater Lake and Lassen Volcanic National Parks.

Early Years

Growing up in a small southern California town, Dinger’s family had many happy adventures backpacking in the Sierra Nevada mountains that towered above them. Those times in the mountains were formative to him. He also knew that he wanted to be a biologist since his first high school AP Biology class. “It was cellular and molecular level biology. I found the intricacies fascinating.”

Education

He began college at UC Riverside with an interest in reptiles and ocean life. But a simple twist of fate (or two) shifted his thinking. First, the summer after his freshman year, working as a camp counselor on Catalina Island, he watched a miserable, dry-heaving camp counselor get whisked off by helicopter to the hospital after a rattlesnake bite. That ended his herpetology interest right there. And second, after transferring to UC Santa Barbara, his first field lab course introduced him to freshwater biology in a lake in the Santa Barbara Mountains. Once he realized he could study aquatics in his beloved mountain landscapes, there was no turning back. He promptly left the world of marine biology behind.

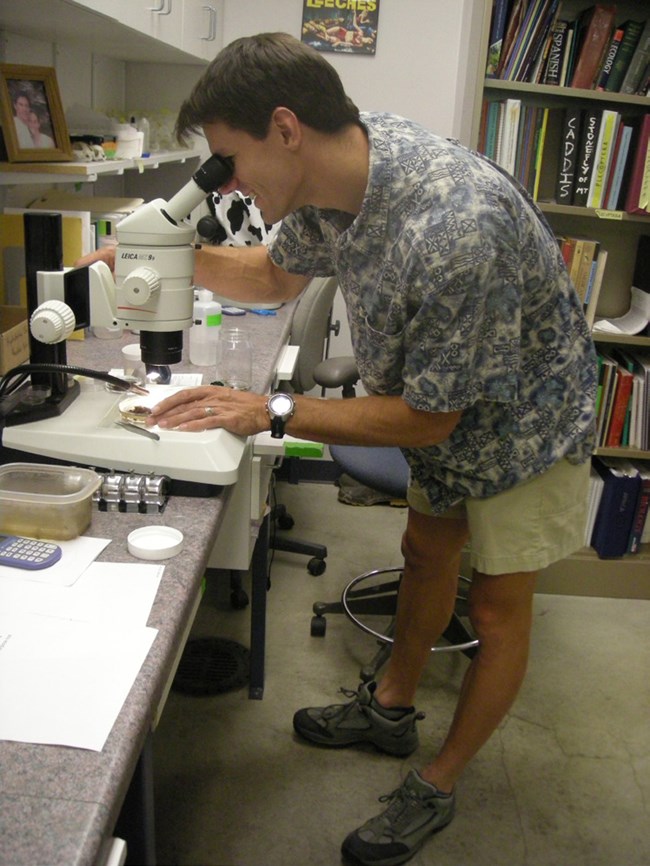

During his undergraduate studies, Dinger did volunteer lab work identifying insects. Soon after graduating, he was hired by Sierra Nevada Aquatic Research Lab (SNARL) as an entomologist. With the lab, he collected aquatic insects in mountain streams of the Eastern Sierra Nevada mountains. This introduced him to the concept of bioassessment sampling, where the abundance and variety of stream insects is used to indicate stream health. This aquatic insect thread would continue throughout his career.

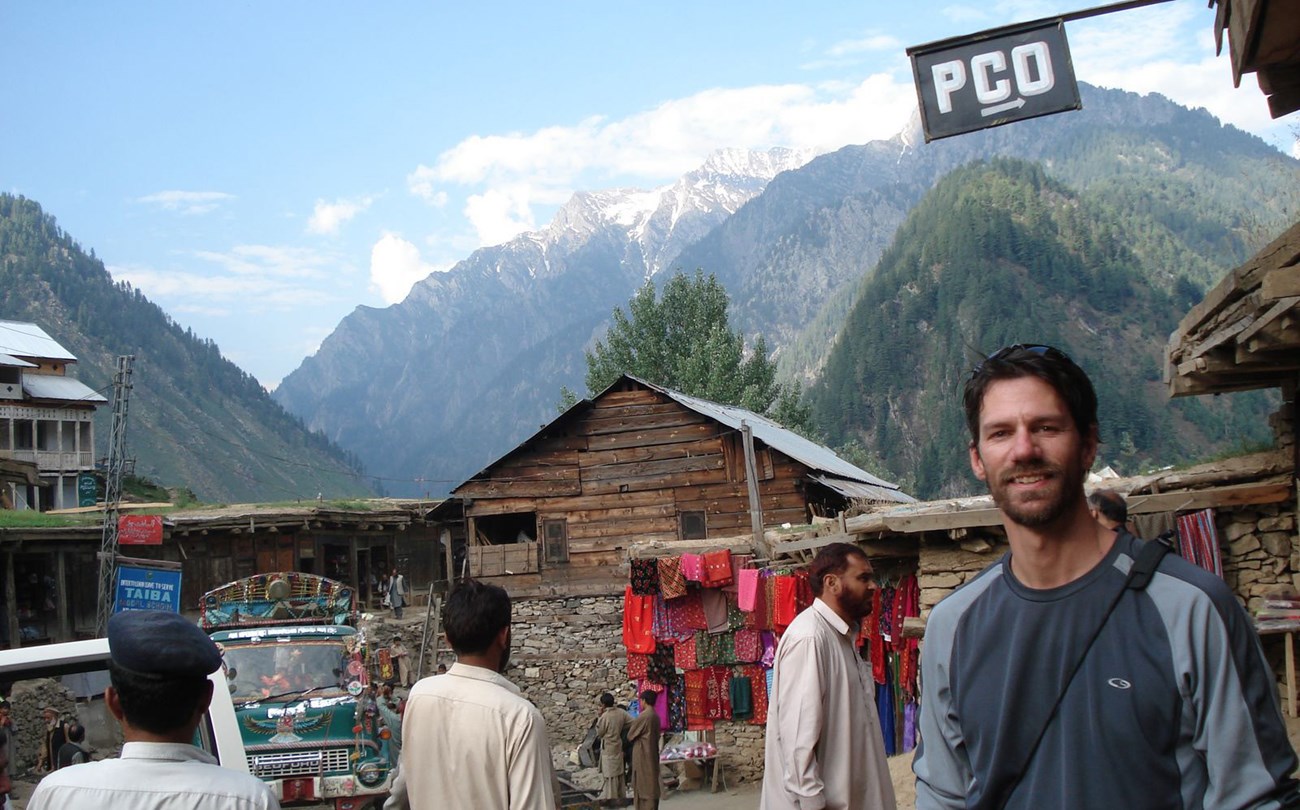

Dinger eventually went on for his PhD at Northern Arizona University, graduating in 2006. During those years, his focus narrowed down to the microscopic world of aquatic insects, and he became even more expert at identifying stream bugs. But other experiences also propelled him outwards for two international stints. He researched modern, living stromatolites in a unique wetland area of Mexico called Cuatro Ciénegas, which translates to “four marshes.” These unique wetlands harbored a wealth of endemic aquatic life, including an aquatic box turtle that evolved over time from living in the water to living on land and then back to living in the water. He also had the opportunity to spend a week in Pakistan with a team of hydrologists and other scientists. They were consulting for the Pakistani government to understand downstream impacts to Pakistan from proposed water diversions in the Kashmir region upstream in India.

Career

After a few years bent over the microscope as an aquatic macroinvertebrate taxonomist with the National Aquatic Monitoring Center (the “USU Bug Lab”), Dinger applied for his dream job in Ashland, Oregon, with the Klamath I&M Network. “There is only so much sitting at a microscope that you can do…” The network hired him in 2008 and he’s been here ever since.

Dinger’s job entails a wide variety of tasks, all related to helping park managers understand the health of their streams and lakes. While he is busy year-round, spring and summer are his “crunch time.” From hiring and training crews, collaborating with parks on logistics and safety for his crews, as well as ordering supplies, it’s the time to do that most essential task of monitoring: collect data. The crews scour the streambed or lakeshore to collect stream insects, immerse hightech water probes to measure water quality, survey for amphibians and fish, and measure stream or lakeside vegetation. The tools of the trade require anything from forceps and a fine mesh net, to laser rangefinders (to measure riparian forest tree heights or distance to opposite shore), to a $10,000 electroshocking backpack unit. Being out in the parks to train his crews is a real source of joy:

“The highlights of this job are being out in the field and shouting at my crewmembers over the roaring water, teaching them how to do stuff. And then seeing them take it and do it as well or better than I was. And knowing that the monitoring is in good hands. And I can leave them to their own devices and I will get quality data from them. Those are the joys of my job. Being outdoors and teaching people.”

Dinger’s “quiet time” comes at the end of field season. Fall and winter keep him busy analyzing data, writing reports, and writing proposals for side projects and funding. A good example was funding he obtained in collaboration with Whiskeytown NRA managers to do some extra stream sampling after the Carr Fire ravaged 97% of the park. The data his crews were able to collect immediately after the fire will help inform park management decisions. Another focus of his quiet time is data analysis. Thanks to his statistical chops (refined in graduate school), he does much of the complicated analyses required for status and trend reporting of network vital signs. Lately, this means using statistical analysis to answer questions like, Can we sample fewer sites or sample them less often without losing our power to detect change? or, How might cave wall bacteria communities respond to the experimental use of UVC light to destroy the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome in bats?

Challenges and the Future

Some of challenges of the job are physical—sampling in hot, muggy, buggy environments. He recounts one painful memory of “…working in the deserts of Mexico where you had Naucorids, a type of water bug, that would love to get into your neoprene booties and bite you between the toes. That was just constant – biting bugs.”

Other challenges of his work are more abstract. For example, the tension between consistency vs. flexibility in monitoring can be frustrating. Long-term monitoring takes time, consistency, and a majority of the network’s budget. At the same time, parks still have short-term emerging issues and management questions that could not be anticipated and are not specifically addressed by long-term monitoring data. Despite the challenges, Dinger has actually been able to provide some help to parks outside the normal long-term monitoring routine. One example is working with Whiskeytown NRA managers to assess the damage from flooding of Crystal Creek after the emergency bypass system was activated at an inopportune time. His lakes crew was able to add some extra sampling into their field season to collect the needed data.

What has been the most meaningful part of his job? A couple of themes emerge. Human interactions have been a highlight for him, from the experience of working closely with Mexican biologists, to a strange encounter during fieldwork in the middle of the desert with two musicians who became good friends, to mentoring individual field crewmembers through their early careers. He still keeps in touch with several of his past employees.

He’s also excited to help drive the evolution of the Inventory and Monitoring Division in its constant efforts to better serve park managers. He notes that since the program’s origins with strictly defined monitoring protocols, I&M scientists have increasingly found ways to meet specific park needs while maintaining consistent long-term monitoring, even though it’s not an easy balance to strike. He’s especially excited to design and carry out science that helps parks continually learn about lake and stream habitats. He hopes that “40 years from now we are still in this learning process and that we never stop learning. It’s the compounding interest of knowledge.”

Joys

Outside of work, Dinger finds his fun back at high elevation for adventures like rock climbing and mountaineering. But fun also revolves around his family. He talks fondly of “…turning rocks over in the streams with my 8-year-old daughter. And just enjoying watching her pick flowers for her mother. Wanting to find that big rock in the middle of the stream that she can sit on and just listen to the noises of the forest.”

Article by Sonya Daw, Klamath Inventory and Monitoring Network

Adapted from The Klamath Kaleidoscope newsletter, Spring-Summer 2020 issue, by Jessica Weinberg McClosky