Last updated: April 24, 2023

Article

Uncovering Fruit Tree History in Rock Creek Park Landscapes

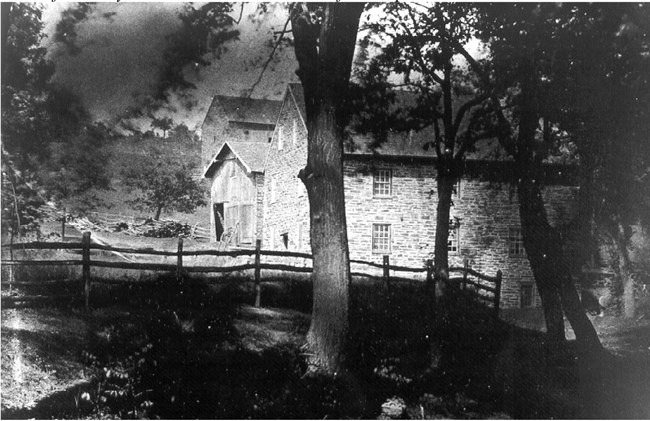

Photograph by Titian Peele. In NPS Peirce Mill Historic Structure Report

Trees form a dense canopy on a steep bluff overlooking Rock Creek in northwest Washington, DC, framing the Peirce-Klingle Estate at Linnaean Hill. Here, several structures stand on level terraces cut into the slope, and the open grassy areas and entry drives hint at its appearance a century ago. The Linnaean Hill landscape contains traces of its history as a commercial nursery, often considered to be the first in Washington, DC, and later its design as a picturesque-styled park with recreational and aesthetic value.

About a half mile to the north, also on the western bank of Rock Creek, Peirce Mill is a remnant landscape with features that represent periods of use and development as a milling and agricultural enterprise. It was later renovated as a picturesque tea house and picnic ground. When the mill and barn were first restored in the 1930s, the landscape began to be used for interpretive programming.

While orchards and fruit trees were once prevalent across Washington, DC, few remain in Rock Creek Park. Today, partner organizations, volunteers, and the National Park Service team up to care for natural and cultural resources of the park, including the mature fruit trees that are still part of the Linnaean Hill landscape and a young demonstration orchard at Peirce Mill.

Landscape History: Peirce Mill

In 1794, Isaac Peirce purchased about 150 acres along Rock Creek, which included a pre-existing house and two-story mill. The enterprising Peirce accumulated additional property and took advantage of the growing economy of the new capital city. He oversaw the operations of a farm, sawmill, gristmill, distillery, and nursery that relied primarily on enslaved labor.

Peirce Mill was established as what is sometimes called a custom mill. Local farmers brought grain to the mill to be ground into flour. By raising the level of a stream with a wooden dam and directing the flow of water through a channel, enough water power was generated to turn the mill wheel and operate the simple machinery that would grind grain and collect meal. This operation of the farm and mill was reflected in the agricultural character of the surrounding landscape, with outbuildings, meadows, orchards, and fences for gardens and livestock.

When Isaac died in 1841, the mill passed to his son Abner Cloud Peirce. A stonemason by trade, he produced grains and potatoes on the property and raised bees, but he did not appear to participate in commercial fruit growing. He passed the property to his nephew Pierce Shoemaker in 1851. Both Peirce and Shoemaker also relied on enslaved labor for their operations. Although there is no record in the census of orchard production during Pierce Shoemaker’s tenure, the 1861 Boschke map of Washington indicates the presence of an orchard northwest of the mill. Shoemaker transferred the land associated with the mill to the federal government for the creation of Rock Creek Park in 1892.

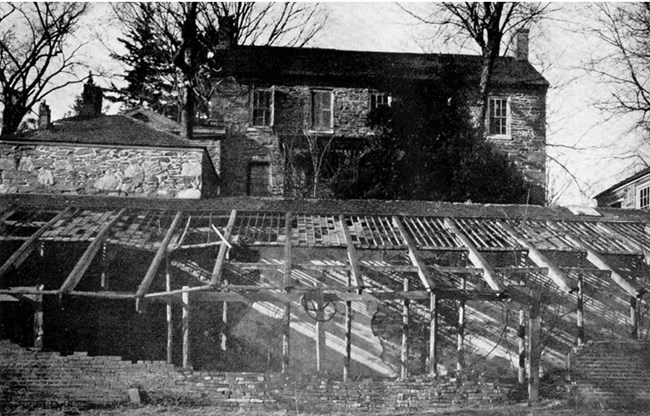

Library of Congress

Even before the creation of Rock Creek Park, the area around the mill was a popular destination among citizens of the District of Columbia for relaxing, picnicking, painting, and walking. A refreshing drink of apple cider was known to have been offered to Peirce Mill visitors. Extensive changes were made to the Peirce Mill landscape during a mid-1930s restoration, associated with Works Progress Administration (WPA) funding and labor. Representing a vernacular industrial landscape of the 1800s, picturesque park destination of the early 1900s, and WPA-era living history museum, Peirce Mill is currently used for interpretation and passive recreation.

Landscape History: Linnaean Hill

Isaac Peirce and Elizabeth (Betsy) Cloud had nine children. Joshua Peirce, their eight child, grew up to be a significant figure in the development and refinement of a portion of the original Peirce tract, which eventually became known as Linnaean Hill.

Isaac Peirce deeded the 82-acre property to Joshua Peirce in 1823, the year that the stone house was constructed. Joshua Peirce also built a greenhouse and two potting sheds on the property. Within a few years, he had established the Linnaean Hill Nursery where he cultivated "Fruit and Ornamental Trees and Plants, Bulbous Flower Roots, Green House Plants, ETC," according to a 1824 catalog title. He probably inherited Isaac’s existing nursery, which contributed to his wide selection of plants.

Joshua Peirce worked to establish his reputation as a nurseryman by expanding his selection of plants, building business relationships with other well-known commercial nurseries, and using propagation and grafting techniques. He adapted his property to suit his business, and evidence of these developments can be seen in descriptions of the grounds at Linnaean Hill, old maps and photographs, and existing landscape remnants.

Washington: D. McClelland, Blanchard & Mohun, 1861. Library of Congress.

Meanwhile, events in Washington, DC around this time influenced the interest in landscape beautification. In 1850, President Millard Fillmore and his wife Abigail invited Andrew Jackson Downing, American landscape architect and editor of the Horticulturalist, to landscape the White House grounds. At the same time, Downing received a commission to design the new Smithsonian site. Peirce may have later provided trees and shrubs from his nursery for plantings at the U.S. Capitol, White House, and President’s Park, although additional research is needed to confirm this.

Joshua Peirce was seemingly influenced by Downing’s style. By 1866, he accentuated the hilly Linnaean Hill landscape with specimen trees, fruit trees, and shrubs and laid out walks and drives that followed the terrain, curving gracefully around the house and buildings. As the picturesque style became more pronounced, the landscape associated with the nineteenth-century nursery enterprise diminished.

When Peirce died in 1869, he left Linnaean Hill to his nephew Joshua Peirce Klingle. While Klingle seemed to share an interest in horticulture, there is little indication that he made significant changes to the landscape. After Klingle's death in 1892, the property was transferred to the United States government for the creation of Rock Creek Park, which had been established by legislation in 1890. Klingle's passive approach to stewardship helped to maintain the picturesque landscape of Linnaean Hill, which was a popular among local residents for recreational uses.

In NPS Cultural Landscape Inventory

Finding Evidence of Orchards and Fruit Trees at Linnaean Hill

Evidence of Joshua Peirce’s Linnaean Hill landscape appears in two topographical maps, one published by Boschke in 1861 and one by Michler in 1867. Each one helps to illustrate the layout of the property, including the residence, roads, clearings, and orchards and other vegetation. The maps also show the gradual development of Peirce’s land for both functional and aesthetic purposes. In addition to being the scene of a profitable business, the grounds were arranged to create a horticultural park, where local residents came for pleasure and recreation.

The orchard was laid out near the northwest portion of Linnaean Hill on the side of a ridge. Peirce published a nursery catalog for distribution, listing his large selection of trees and shrubs and including an essay on the planting and cultivation of orchards. In the catalog, he recommends that a farm orchard be laid out with a space of forty feet between trees, and the surrounding ground might be cultivated with vegetables or grains and fertilized with manure. Nursery laborers also likely used the greenhouse to care for seedlings and grafts.

Peirce adapted many of his catalog recommendations for success in his own plantings. To establish and maintain such an enterprise, Peirce and his wife enslaved as many as 13 people (according to the 1840 Census). In later years, the focus and scope of the business shifted. The nursery operation was centered on a property on 14th Street, and Peirce’s occupation listed in the census changed from “Nurseryman and Florist” (1846) to “Farmer and Nurseryman” (1850) to “Horticulturalist” (1860). By 1860, Peirce could operate the estate with less help, which included his nephew Joshua Peirce Klingle.

Olmsted Archives, Item 2837-5-sh7. Courtesy of the United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

NPS

Although the exact age and variety of individual trees have not been determined, the mature size of two extant fruit tree specimens suggests a planting date in the 1800s. Both trees, one pear and one cherry, are located near the Peirce-Klingle mansion. Techniques like dendrology can be used to determine the age of existing trees. Varieties can be identified with the help of DNA analysis, which can be compared to the offerings in the orchard catalog.

When the Peirce-Klingle Estate was transferred to the new Rock Creek Park, much of the picturesque planting design and horticultural nursery plantings were still evident. In the 1930s, a Colonial Revival landscape was installed, introducing new vegetation and designs. In subsequent years, the landscape around the house reverted from largely open space to native and invasive vegetation.

Connecting Past and Present

Orchards and Fruit Trees at Rock Creek Park Today

As with many nineteenth-century horticultural sites of this kind, vegetation at Linnaean Hill has reclaimed much of the landscape perimeter, as historic ornamental trees and shrubs have been lost or absorbed into the understory and overgrowth. Today, vegetation management at the site focuses more on the priority of controlling invasive species than care for individual specimen trees.

A group of volunteers meets routinely at Linnaean Hill to remove invasive species, led by Rock Creek Park Botanist Ana Chuquin. In spring of 2023, Chuquin will guide these volunteers in the potential discovery of other remaining mature fruit trees. Fruit trees that are engulfed in encroaching vegetation are more easily detected when their blossoms emerge in spring. The group can use an app like iNaturalist to assist with identification and documentation of pear, apple, and cherry trees. This effort will help future landscape documentation efforts and open a different perspective of Linnaean Hill.

Other than the two old fruit trees near the house, there are no documented remnants of the nursery that once grew at Linnaean Hill. However, visitors can find a demonstration orchard at nearby Peirce Mill. The orchard, installed in 2012, is maintained by the Friends of Peirce Mill, which partners with the National Park Service at Rock Creek Park to preserve and interpret the gristmill and surrounding landscape.

The orchard at Peirce Mill is more than just a collection of fruit trees. Tim Makepeace, orchardist and Board President of the Friends of Peirce Mill, described some of the actions to maintain the orchard as part of the historic mill landscape. The orchard contains grafted trees, including a few varieties listed in Joshua Pierce’s extensive nursery catalog.

Courtesy of Friends of Peirce Mill

Makepeace plants a mix of spring grasses, including wheat and rye, as a cover crop under and between the trees, maintaining a clearing around the trunk to reduce competition and prevent damage from voles. The grasses helps to depict the historic setting of the mill. Traditionally, the height and spacing of orchard fruit trees allowed for crops to be grown among them while waiting for the trees to mature. The cover crop also contributes to soil rejuvenation, nutrient cycling, and pest management. Livestock and chickens historically browsed under orchard trees, controlling grass and bugs and fertilizing the trees with manure.

Most trees in the demonstration orchard are pruned into what is sometimes called a Modfied Central Leader form. Three or four branches are selected to form the main scaffolding of the tree. This allows more light to reach the middle branches, keeps the overall height of the trees lower, and favors fruit production over growing vigor. Trees pruned in the Central Leader style also grow in the orchard, so visitors can see both forms. A fence surrounds the entire orchard to keep out deer and browsing animals.

Preservation Partnerships

While Peirce Mill and Linnaean Hill are two distinct cultural landscapes that represent different periods in history, the historic landscapes are connected by location and family ties. The fruit tree history of both sites is interpreted at Peirce Mill, inviting visitors to imagine past uses of the land and the people who interacted with it.

Both areas of Rock Creek Park are scenic landscapes that offer recreational opportunities, interpretation of the historic landscape, and exploration of the natural surroundings. The demonstration orchard at Peirce Mill is a tangible, living reminder of the agricultural history of the landscape, and it presents an image of the varieties, characteristics, and maintenance of orchards that historically grew in the area. The pear and cherry tree at Linnaean Hill help to establish the landscape’s significance in fruit tree production and also illustrate the picturesque design of the estate. Uncovering more information about the remnant trees at Linnaean Hill will add to this understanding.

The National Park Service, Friends of Peirce Mill, and volunteers all play a critical role in caring for these fruit trees as cultural and natural resources.

Get Involved

Additional Resources

Dryden, Steve. Peirce Mill: Two Hundred Years in the Nation's Capital. Bergamot, 2009.

Kramer, Angela. "Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse." Washington History 34, no. 2 (Fall 2022): 50-59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/48694020

Saul, John A. "Tree Culture, or a Sketch of Nurseries in the District of Columbia." Records of the Columbia Historical Society 10 (1907): 38-62. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40066955