Part of a series of articles titled Intermountain Park Science 2021.

Article

Responding to Climate Change in the Southeast Utah Parks

- Terry T. Fisk, Chief of Resource Stewardship and Science, Southeast Utah Group, National Park Service (currently Water Rights Branch Chief, Water Resources Division, National Park Service).

- David Thoma, Hydrologist, Northern Colorado Plateau and Greater Yellowstone Networks, Inventory and Monitoring Program, National Park Service.

Concerns about Climate Change in Southeast Utah

Climate change is a factor that is affecting natural and cultural resources in southeast Utah. Dealing with the effects of climate change on park resources demands considerable knowledge and planning in order to understand complex effects and to select and implement effective responses. Knowing what to do can seem daunting, but despite the formidable difficulties, there is an urgency to understand and prepare. We are “on the ground” in our parks and we are engaging with the crisis and fulfilling our stewardship mission for these sacred lands. Our intent here is to describe our recent accomplishments.

Pronounced long-term drought and associated reductions in water availability to ecosystems have emerged as predominant characteristics of climate conditions in the southwestern US, including the Colorado Plateau. The Colorado Plateau is experiencing increasing temperatures, greater moisture deficits, and increasing aridification (Cook et al. 2015) that present considerable challenges to the National Park Service (NPS) Southeast Utah Group parks (Arches National Park, Canyonlands National Park, Hovenweep National Monument, and Natural Bridges National Monument). Climate data for the period 1901 through 2012 indicate that Southeast Utah Group parks already are experiencing climate conditions that are shifting beyond the historical range of variability. For example, in Canyonlands the warmest quarter of the year, the warmest month, and the driest month are at or above the 98th percentile of historical conditions (Monahan and Fisichelli 2014). Robust general circulation model ensemble predictions suggest that, in the next 50 to 80 years, the parks will likely experience annual moisture deficits 22% to 33% greater than historic 1950 to 2000 averages (Alder and Hostetler 2013). This suggests it is dry and getting drier, but Cook and others (2015) evaluated “megadrought” conditions on a millennial-length time scale and concluded that drought in the late 21st Century will likely exceed the most severe megadroughts occurring in the southwestern US during the period when the Chacoan Culture and other southwestern indigenous cultures were severely disrupted. Megadroughts are multidecadal periods of intense aridity that exceeded the duration of any drought observed during the historical record and had profound impacts on regional societies and ecosystems (Cook et. al. 2015, Steiger et.al. 2019). The looming drier future will be far outside the contemporary experience of natural and human systems in the southwest (Cook et al. 2015). As a result, increasing aridification and drought stress is the most significant resource issue facing Southeast Utah Group parks.

What Do We Do Now?

The Southeast Utah Group of parks has begun preparing for the substantial impacts that climate change will have on natural and cultural resources and visitor experience. We started by acknowledging that the options that species have for dealing with climate change are few. Species can adapt, migrate or perish. Which of those is most likely can be determined via formal vulnerability assessments that are components of the research and monitoring projects described below. Managing these outcomes boils down to three strategies that include resisting, accepting or directing change. That is, managers can resist change (e.g. water drought-stressed vegetation); they can accept change and observe how it plays out; or they can direct change in ways that result in a desired outcome, such as implementing assisted migration or restoration with species that are adapted to new climate conditions (Thompson et al. 2020). The hard choice of selecting a management strategy is determined by values, policy and law. Nevertheless, it comes with an understanding that some species and resources will be saved and some will be lost. Similar decisions will have to be made to deal with changes that affect cultural resources. Our approach favors directing change when and where it appears viable and within the boundaries of law and policy. However, we recognize that some changes will require acceptance and observation as transitions unfold. We expect to learn from these transitions to better prepare for additional future change.

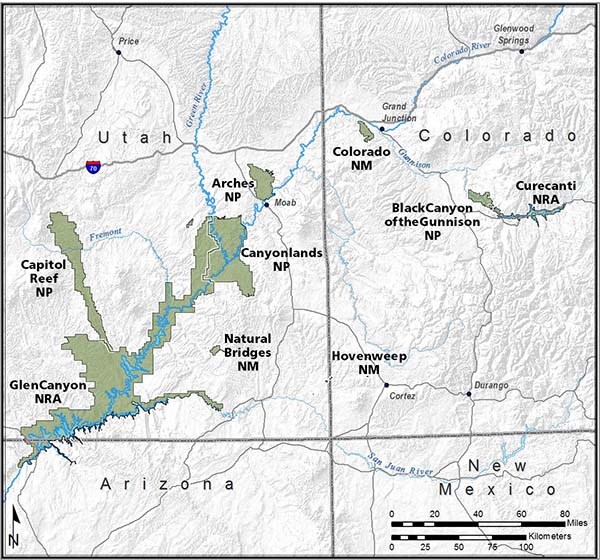

In December 2018, 35 people convened at the Southeast Utah Group Climate Change Workshop. Participants included individuals from Northern Arizona University, US Geological Survey (USGS), NPS Northern Colorado Plateau Inventory and Monitoring Network, and parks of the Southeast Utah Group: Arches, Canyonlands, Hovenweep and Natural Bridges. Other parks with representatives attending included Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park/Curecanti National Recreation Area, Capitol Reef National Park, Colorado National Monument, and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Park locations are shown in Figure 1.

Objectives of the climate adaptation workshop were to:

-

Build a shared vision for climate adaptation management strategies and research needs.

-

Refine conservation targets for focusing climate adaptation planning and research.

-

Generate an initial set of management options that could be implemented in certain circumstances, either given current knowledge or contingent on additional information.

-

Identify existing data, tools, and research that can support management needs.

-

Identify high priority information gaps and how they can be filled.

-

Agree on paths forward and strategies to stay coordinated.

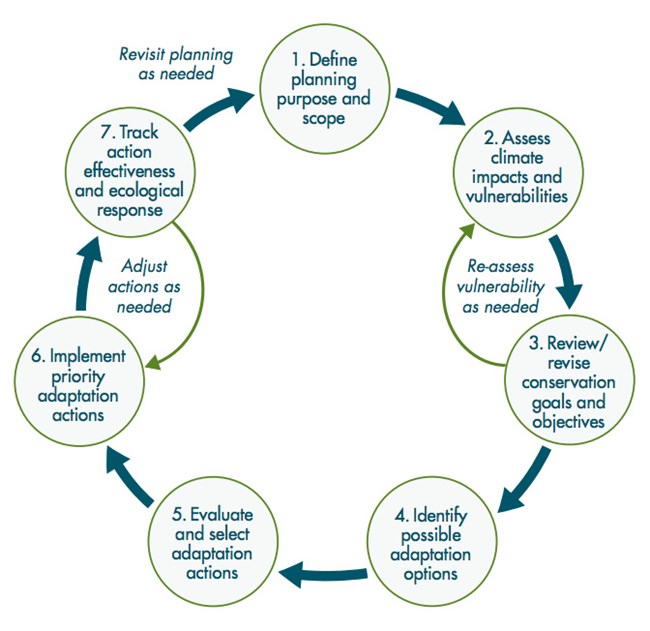

David Thoma taught workshop participants about conducting climate change vulnerability assessments (Glick et al. 2011) within the Climate Smart Conservation framework (Stein et al. 2014): a set of proven strategies for climate adaptation planning. The Climate Smart Conservation framework (Figure 2) was developed by a consortium of federal agencies and the National Wildlife Federation and guides users through a systematic, structured assessment of adaptation options. Thereafter, participants learned from each other as individuals with specific expertise and experience. Workshop participants shared current research on the climate trajectory for the region, discussed existing information and best methods to assemble and use it, and explored ideas for using climate projections for adaptation planning and weather forecasting to identify management triggers for implementing management plans at the right time in the right place. Outcomes of the workshop included commitments to move forward with climate adaptation planning efforts using an adaptive management approach that includes experimenting with resource protection and restoration needs, developing partnerships, and cultivating tribal involvement in climate adaptation planning. Participants also decided to explore ways to implement adaptation strategies across multiple park units and in collaboration with other jurisdictions.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 2019.

The workshop was a tremendous success because individuals were highly motivated and we included the correct mix of people: decision-makers, scientists, communicators, and stakeholders. The group summarized existing knowledge on the magnitude, and spatial and temporal scales of expected changes across park landscapes. This helped identify conservation goals in the context of vulnerability that centered on grassland conservation, while initiating follow-on projects focused on shrubland and pinyon-juniper (two-needle pinyon pine [Pinus edulis] and Utah juniper [Juniperus osteosperma]) woodland communities. Establishing the initial goal of focusing on the vulnerability of grasslands, followed by shrublands and pinyon-juniper woodlands, helped identify research needed to better understand climate impacts that can help make decisions in the context of long-term exposure to aridification.

Using Science to Inform Goals and Strategies

Much excellent research has been and is being conducted regarding effects of climate change on the Colorado Plateau, and the body of knowledge is quite impressive. Research on vegetation response to climate in parks based on long-term monitoring informs our understanding of the vulnerability of vegetation to climate change. However, important topics that can help parks define a possible suite of management options still need to be explored more fully.

A key element of the future planning and preparation process is that, concurrent with the workshop planning, Southeast Utah Group successfully partnered with the USGS Southwest Biological Research Center (Flagstaff, Arizona and Moab, Utah) to compete for funding from the combined NPS-USGS Natural Resources Preservation Program. In January 2019, our group was awarded funds to conduct climate change-related research through fiscal year 2021. The way the research project fits into Climate-Smart Conservation is shown in Figure 2. The project focuses on grassland, shrubland, and pinyon-juniper woodlands vegetation communities and is intended to accomplish the following.

-

Quantify the magnitude, and spatial and temporal scales of expected physical changes across park landscapes. This work encompasses quantifying expected changes in soil moisture, temperature, and precipitation at daily to annual time scales across the high diversity of ecosystems supported by Southeast Utah Group parks.

-

Understand probable effects of aridification, focusing on the most vulnerable resources in terms of climate exposure, sensitivity to climate, and adaptive capacity (components of vulnerability) to handle the rate and magnitude of climate change.

-

Implement place-based short- and medium-term applied ecological forecasting to help guide resource management decisions and capitalize on forecasted opportunities to optimize response actions, such as knowing when and where to implement restoration activities that have the greatest likelihood of success.

-

Incorporate research findings and forecasts into management plans and actions. Identify actions that minimize the impacts of aridification by decreasing the vulnerability of resources to forecasted change.

Deliverables will include a Climate-Smart Conservation Plan for Southeast Utah Group vegetation communities and a prototype decision support tool that will enable forecasting aridity-driven vegetation stress based on current conditions and expected future drought. A series of peer-reviewed publications will also be forthcoming.

NPS/Terry Fisk.

NPS/Terry Fisk.

-

Describe how soil and climate interact to affect vegetation within Colorado Plateau drylands based on soil type, topography, and species-specific drought resistance,

-

Create a process-based understanding of the climate, soil, and vegetation framework through modeling of soil water dynamics and plant physiology,

-

Assess ecosystem sensitivity and vulnerability under modeled future soil moisture conditions for each soil-geomorphic unit to predict the heterogeneous response of Colorado Plateau drylands under future climate conditions, and

-

Develop climate vulnerability maps to be used by NPS managers and other agencies when assessing broad-scale climate sensitivity, developing resource monitoring programs, and planning active restoration activities.

These two projects are the first major climate change-related steps in building long-term decision support relationships between resource managers and research scientists that can sustain the cyclic, ongoing, adaptive conservation approaches that are recognized as the best strategy for managing resources in a time of dramatic environmental change. As we develop experience, we will build on these projects and expand our efforts to other areas such as cultural resources, wildlife, and water resources.

Maintaining Momentum

Post-December 2018 workshop actions have included additional outreach to stakeholders, formalizing USGS and park study plans and implementing research. Bimonthly conference calls among a core group of park, Northern Colorado Plateau Network, USGS, and Northern Arizona University employees have helped maintain momentum for continued outreach and planning.

For example, the USGS Southwest Biological Science Center hosted a half-day session on the topic of land manager-researcher collaboration during the 15th Biennial Conference of Science & Management on the Colorado Plateau & Southwest Region held at Northern Arizona University in September 2019. The session focused on the challenges of integrating science and management actions in an era of increasing drought severity and presented the results of USGS project-related research during the first eight months of 2019. This description included evaluating the sensitivity of grasslands based on temporal and spatial responses to precipitation and temperature.

The Southeast Utah Group has also invited associated Tribes to participate in formal government to government consultation regarding the effects of climate change in the parks — their ancestral lands. We hope that consultation will lead to long-term involvement by Tribes in research, application of traditional ecological knowledge, and evaluation of potential management actions.

Based on feedback at the 2018 workshop and periodic discussions during 2019, evaluation of the vulnerability of pinyon-juniper woodlands across a range of parks and monuments in the region was initiated formally at a second workshop held in December 2019 in Moab. Not all parks have the same mix of vegetation communities as Southeast Utah Group parks, but most parks in the Colorado Plateau have pinyon-juniper woodlands and it will be valuable to evaluate this community on a much broader landscape scale. As part of the focus on pinyon-juniper woodlands, the USGS has gathered vegetation data for 26 national parks and monuments across the Colorado Plateau and adjacent areas and is beginning water balance modeling using the vegetation data combined with remote sensing of soil moisture. Another avenue of USGS climate change-related research will evaluate the potential for Indian ricegrass (Achnatherum hymenoides), a native species, to be successful in a warmer world, based on new data suggesting some local individual plants may adapt well to warmer and drier conditions.

Helping maintain momentum, the Canyonlands Natural History Association has provided vital financial support to the USGS, totaling $30,000 in 2019 and $61,000 in 2020. These donations have supplemented the USGS-NRPP funding source and have enabled a substantially larger scope of research by the USGS, including engaging with more parks and monuments.

Coming to terms with the magnitude and rate of climate change can seem overwhelming. Our goal is to incorporate climate change-related actions into our daily work flow whenever possible, whether that be planning, field work, data evaluation, research, or implementing a management action on the ground. In essence, we see climate change as a critical new element in much that we do and use the Climate Smart framework as a guide to developing clearly defined goals, responsible strategies and routine actions that promote success. The framework helps us compartmentalize complexity into “bite sized” tasks which makes adaptation seem possible because it is, even if hard decisions about resource winners and losers will have to be made. This new ‘user manual’ helps identify goals and strategies, but it is primarily up to us to determine how we support each other in new roles. Adaptation brings many challenges, but we have new tools and research that will help. There is a role for everyone. For this reason, we look forward to interdisciplinary, inter-agency and cross-cultural collaboration, sharing and learning together in western US parks. It is critical that we engage in this important work, and it is gratifying to know that there is a supportive network of people who are all in this together.

References

Alder, J. R., and S. W. Hostetler. 2013.

USGS National Climate Change Viewer. US Geological Survey. Available at: https://www2.usgs.gov/landresources/lcs/nccv.asp (accessed July 20, 2020).

Cook, B. I., T. R. Ault, and J. E. Smerdon. 2015.

Unprecedented 21st century drought risk in the American Southwest and Central Plains. Science Advances 1(1): e1400082.

Glick, P., B. A. Stein, and N. A. Edelson, editors. 2011.

Scanning the Conservation Horizon: A Guide to Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment. National Wildlife Federation, Washington D.C., 168 pp.

Monahan, W. B., and N. A. Fisichelli. 2014.

Climate Exposure of US National Parks in a New Era of Change. PLoS ONE 9(7): e101302. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0101302 (accessed July 17, 2020).

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 2019.

U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit. Climate-smart conservation: putting adaptation principles into practice. Available at:

Climate-Smart Conservation: Putting Adaptation Principles into Practice | U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit (accessed April 2, 2021).

Steiger, N. J., J. E. Smerdon, B. I. Cook, R. Seager, A. P. Williams, and E. R. Cook. 2019.

Oceanic and radiative forcing of medieval megadroughts in the American Southwest. Science Advances 5: eaax0087.

Stein, B.A., P. Glick, N. Edelson, and A. Staudt, editors. 2014.

Climate-Smart Conservation: Putting Adaptation Principles into Practice. National Wildlife Federation, Washington, D.C., 262 pp. Available at: https://www.nwf.org/climatesmartguide (accessed July 20, 2020)

Thompson, L. M., A. Lynch, E. Beever, A. Engman, S. Jackson, T. Krabbenhoft, D. Lawrence, D. Limpinsel, R. Magill, T. Melvin, J. Morton, R. Newman, J.O. Peterson, M. Porath, F. Rahel, S. Sethi, and J.L. Wilkening. 2020.

Responding to ecosystem transformation: resist, accept, or direct? Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 46(1:8-21).

Last updated: September 9, 2021