Last updated: October 27, 2021

Article

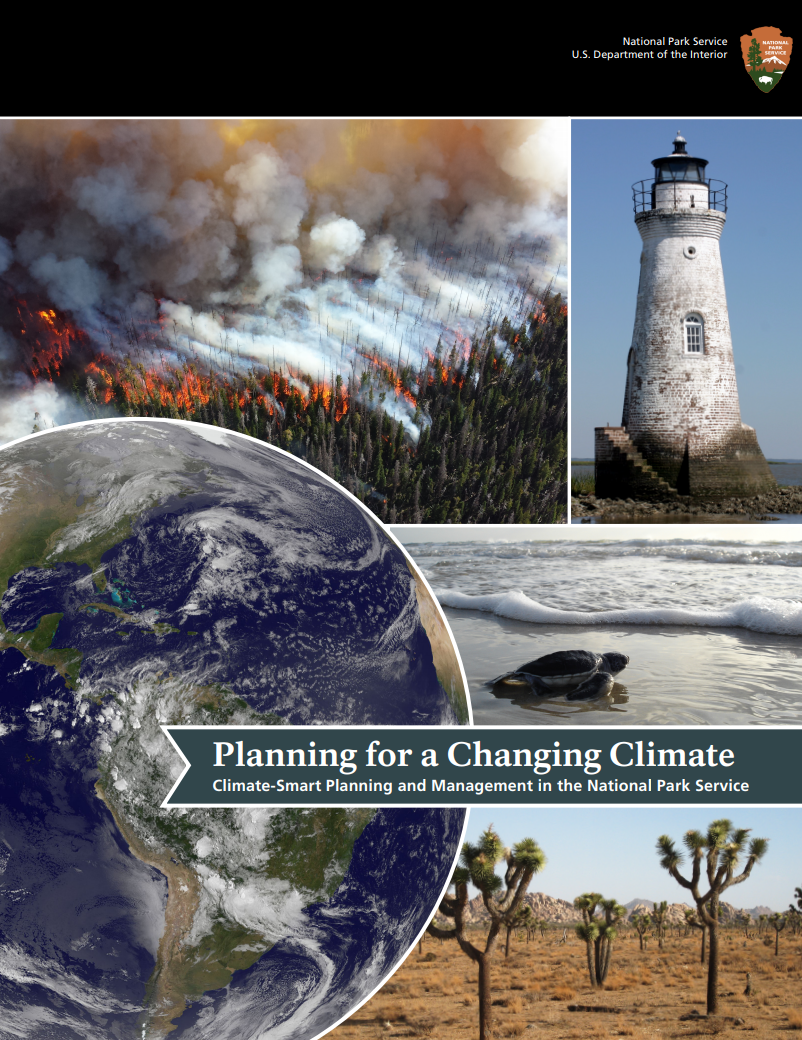

Climate Smart Conservation Planning for the National Parks

Introduction

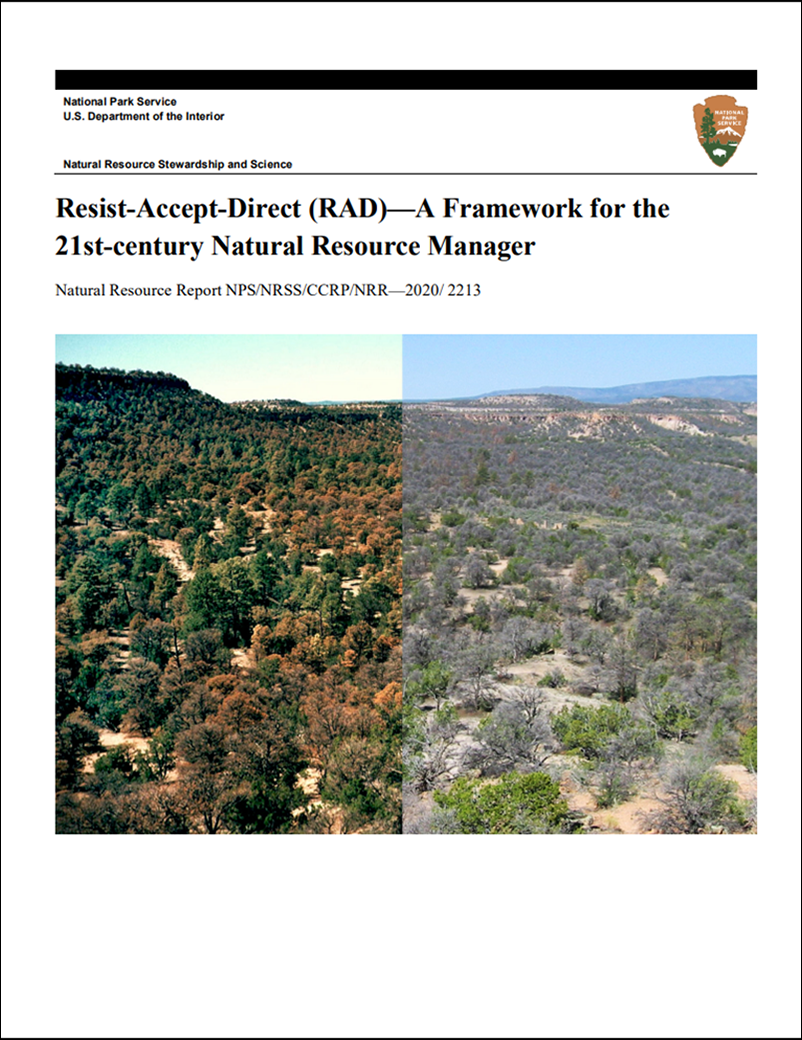

Plants and animals in national parks of the U.S. Southwest are adapted to arid conditions, but even desert dwellers have their limits. Entire forests of pinyon-juniper have been killed by bark beetles, and others have been killed by drought. Wildland fires and floods are more severe. Snowpack is declining. Erosion is increasing. Climate projections for a hotter and drier future suggest more change is coming.

In response, park managers are having to rethink how they plan for the future. The National Park Service (NPS) is responsible for conserving park wildlife, scenery, and natural objects. For many years, this was taken to mean that park landscapes should be managed to look like they did at some point in the distant past. Management objectives have evolved since then—but it’s worth noting that even in the most remote wilderness parks, the ecological conditions that created today’s park landscapes often no longer exist.

Under changing climatic conditions, park management options may range from working to ensure persistence of historical or current states, to accepting change, to directing complete ecosystem transformation. The decisions can be scientifically challenging—and emotionally agonizing. But many park staff are discovering a tool that can help.

Climate Smart Conservation is a process for identifying actions that can help managers achieve goals in the face of coming changes. Together, scientists and managers think through potential climate impacts to park resources, use scientific data to analyze different situations, and then identify and evaluate management options most likely to be feasible, achievable, and most effective given park capabilities. Under this framework, scientists and managers use their collective knowledge to anticipate problems and be proactive, rather than reactive. The process breaks big, complex questions into bite-sized chunks that bring the outlines of hope into clearer focus.

Adapted from a graphic produced by the National Wildlife Federation.

How it Works

Climate Smart Conservation follows a series of iterative steps. First, managers identify what they hope to achieve relative to a given system or resource. This is hard because it means acknowledging that the future of park landscapes may look very different. The next step is to assess the vulnerability of that system or resource to climate impacts. This is where the science comes in.

Climate change is outpacing the rate of adaptation for many plants and animals, but not everything will change at once. How vulnerable a species is to climate change depends on more than sensitivity. For instance, its level of exposure to change (i.e., how quickly and/or dramatically its environment is changing), helps determine how likely it is to be able to adapt to potential impacts. Some species are more sensitive to small environmental changes. Other species are less sensitive. In combination, exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity make a species more or less vulnerable. They also make action more or less urgent, and conservation more or less likely to succeed. At this stage, it’s crucial to have access to long-term ecological monitoring data, like that produced by the NPS Inventory & Monitoring Division. Combined with climate data, long-term monitoring data can help identify what, where, when and why natural resources may change in response to climate.

Because we can't be certain of what will happen in the future, Climate Smart Conservation considers different scenarios of potential change when assessing vulnerabilities. This helps with the next phase of the process: identifying adaptation actions that are robust to a range of plausible future climate conditions.

But first, it’s time to re-assess the initial conservation goals. If a park’s primary goal was to conserve a species found to be highly vulnerable to expected future conditions, it may be necessary to modify the goal. But if the original goal still appears achievable, then the process moves into the identification, evaluation, and implementation of different management options. Here, park managers again take the lead, providing park-specific expertise about which types of actions and strategies are most appropriate and possible.

The final step is to monitor the effectiveness of the management actions to determine if further adjustments are needed.

Why It’s Crucial

This intentional planning process helps park managers to anticipate—and avoid—surprises. Knowing what to expect means being better prepared to deal with it. If we anticipate drought, then we can thin forests now to reduce the chances of severe wildfire later. If we know water rights may be threatened, then we can start negotiations today. If we expect an important species may not persist in the future, then we can identify another native species that may help fill its role in the ecosystem. Knowing that certain plants and animals may feel stress before they actually experience it can help managers take appropriate actions to help those species linger. This is critical because natural systems will eventually adapt to new climate regimes—but outside of asteroid impacts, they’ve never had to adapt so quickly.

Choosing not to explore these questions ahead of time increases the likelihood of undesirable outcomes—like uncontrolled noxious weed invasions, loss of ecosystem structure and function as vegetation transitions unfold, and hydrologic changes that will affect both aquatic species and people. In short, an ounce of prevention can be worth a pound of cure.

NPS/Erin Shanahan

How It’s Being Used

Climate Smart Conservation doesn’t provide all the answers, because they’re not all knowable. It’s also not a process either scientists or managers can complete on their own. It does help park managers focus resources and attention on actions that can provide the most benefit. After participating in Climate Smart Conservation workshops hosted by the Northern Colorado Plateau Network, parks in the NPS Southeast Utah Group are working with U.S. Geological Survey scientists to restore and conserve grasslands and pinyon-juniper forests. In the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, a consortium of federal agencies are engaged in aquatic resource conservation and whitebark pine conservation. Existing projects are reconfigured to accommodate new knowledge of climate stressors, often incorporating new science to make management actions robust to a range of plausible future conditions. Since the first workshop at Moab, Utah, in 2016, the NPS Inventory & Monitoring Division has hosted additional workshops in parks across the West.

Climate change is shuffling the deck for NPS ecosystems. It will play out gradually in some cases and abruptly in others. For park managers, maintaining healthy park ecosystems will require proactive planning—and the difficult acceptance that it may not be possible to save everything. What scientists and managers can do is work together to assist park species where it’s wise to do so, or slow the rate of change. Climate Smart Conservation can help.

Contact

|

|

Additional Resources

Climate Smart Conservation (National Wildlife Federation)

National Park Service Climate Change Response Program

Tags

- arches national park

- canyonlands national park

- hovenweep national monument

- natural bridges national monument

- yellowstone national park

- yosemite national park

- climate change adaptation

- research

- climate change

- climate science

- climate change effects

- ncpn

- sodn

- northern colorado plateau network

- sonoran desert network

- inventory and monitoring

- inventory and monitoring division

- climate change response program

- planning

- resource management

- southeast utah group

- greater yellowstone ecosystem

- gryn

- greater yellowstone network

- us geological survey

- monitoring

- waterbalancecc