Last updated: December 19, 2025

Article

A Fish Study's Promising Results Highlight Parks' Role in Conservation

Protected areas don’t always achieve their conservation goals. Here’s one case where they do.

About this article

This article was originally published in the "In Brief" section of Park Science magazine, Volume 39, Number 2, Summer 2025 (August 29, 2025).

NPS

Streams and rivers are critical to the people, animals, and plants that live in and around them. They provide habitat for fish and other aquatic species. They serve as sources of water for agriculture, cities, and towns. But they’re being degraded faster than most other ecosystems. One strategy used to help conserve them is to establish protected areas like national parks. These areas aim to protect aquatic resources from habitat loss and other environmental pressures. But just because an area is protected doesn’t mean waterways won’t be degraded. Common activities in and around protected areas, like ecotourism, recreation, and resource use, can exert their own pressures on aquatic systems.

National Park Service and other scientists began monitoring stream fish communities in parks in the mid-Atlantic region in 2013. Our recent study, published in the January 2025 issue of Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, shows that stream fish populations in two Appalachian U.S. national parks have remained remarkably stable. This emphasizes the value of these parks for conserving the region’s fish and waterways.

A Vast Network

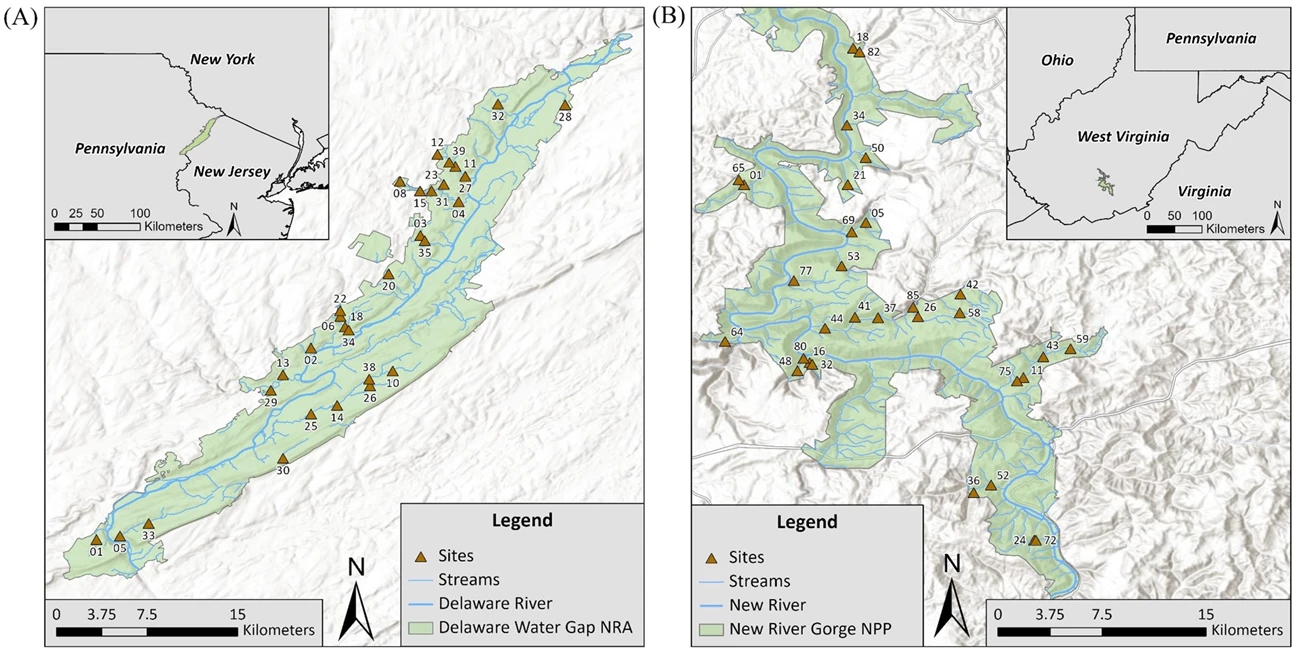

We studied fish communities in wadeable streams throughout Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area and New River Gorge National Park & Preserve. We looked at streams with drainage areas of less than 100 square kilometers, or about 38.6 square miles. These small to medium-sized streams form a vast network throughout the Appalachian Mountains. They supply water for downstream rivers, communities, and estuaries.

Stum and others. 2025. Decadal stability in stream fish communities and contemporary ecological drivers of species occupancy in two Appalachian U.S. National Parks. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 154(1): 17–34.

The fish data were collected through electrofishing surveys in 2013–2014 and 2022–2023. We counted and identified the species of captured fish, then released them back to the stream. The photographs we took helped record key features of the few fish we couldn’t identify on site, so we could examine them later and seek help from other experts. We also collected relevant habitat information—such as stream channel width and the type of vegetation adjacent to the stream—using procedures established by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. We used our capture data and mathematical models to estimate changes in the number of each species in the system through time and how habitat type affected them.

“I think every person who spends time outdoors knows that just because you don’t see an animal, doesn’t mean it isn’t there. These models allow us to focus on the process we actually care about, which is if the fish is at the site or not.”

“These mathematical models are incredibly important,” explained co-author Frances Buderman, assistant professor at the Pennsylvania State University. “Capturing an individual fish is actually the outcome of two separate events: the fish being there and us being able to capture it. I think every person who spends time outdoors knows that just because you don’t see an animal, doesn’t mean it isn’t there. These models allow us to focus on the process we actually care about, which is if the fish is at the site or not.”

Encouraging Evidence

Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area

In the 2023 survey at Delaware Water Gap, we found fish at all but one site, the same "fishless" site as in 2013. We caught over 11,500 fish, representing nine families and 30 species—two fewer than in 2013. The most common species in both surveys were blacknose dace, brown trout, American eel, longnose dace, and brook trout.

Several habitat factors influenced fish distribution. Larger upstream catchment areas generally increased fish presence, while steeper slopes decreased it. Most species, including American eel, were found near the Delaware River. Creek chub lived farther away. Species like largemouth bass and bluegill thrived in warmer waters, while brown trout occupied cooler waters. Brook trout and rainbow trout were less common in areas with over 10 percent upstream development. Blacknose dace and margined madtom were in areas with 20 to 30 percent upstream development.

NPS

NPS

New River Gorge National Park and Preserve

In the 2023 survey at New River Gorge, we found fish at 21 out of 31 sites, with eight sites remaining "fishless" as in 2013. Over 5,600 fish from five families and 16 species were captured—five fewer species than in 2013. As in 2013, the five most abundant species were blacknose dace, fantail darter, rosyside dace, creek chub, and central stoneroller. Notably, we found creek chub at a site in 2023 where no fish were found in 2013, and brook trout were not found at two sites where they had been found in 2013.

Most species at the park occupied lower-gradient, deeper streams.

Most species at the park occupied lower-gradient, deeper streams. Seven species, including all observed minnows, favored warmer stream temperatures. The overall fish community responded positively to better habitat scores, but only blacknose dace and green sunfish were significantly linked to habitat quality. Unlike at Delaware Water Gap, distance to the New River had little effect on most species. But creek chub were more likely to be present farther from the river, similarly to the national recreation area.

Stability and Connectivity

Our data showed that fish communities remained virtually unchanged at New River Gorge, which was excellent news. At Delaware Water Gap, only a few species showed potential declines. Those species (e.g., bluegill and yellow perch) were primarily “unexpected” non-native or pond species, so their absence was a welcome discovery. They likely entered streams from impoundments upstream of park boundaries.

The high number of sites where American eel was found at Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area was also a positive sign, as the species is globally endangered.

The high number of sites where American eel was found at Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area was also a positive sign, as the species is globally endangered and at or near historically low levels in U.S. waters. The American eel is the only freshwater eel in North America. It lives in freshwater as an adult but migrates to the ocean to spawn. Many mid-Atlantic river systems have numerous dams, which limit the eels’ ability to travel. The relative absence of dams in the Delaware River basin helps to support the species. The increase in American eels at Delaware Water Gap aligned with other studies from the Delaware River basin. It underscores the importance of habitat connectivity for migratory species.

NPS

Brook trout, the only native salmonid in the region, remained common, but with a slight decline in occupancy. This decline was likely linked to increased development upstream of park boundaries. Non-native rainbow trout occupancy also declined, but that was likely due to changes in stocking programs.

The prevalence of blacknose dace and creek chub at New River Gorge was largely a result of factors like stream structure and water temperature. The steep, rugged terrain and thousands of cascades and waterfalls at New River Gorge form natural barriers that prevent many fish from colonizing the headwaters. So most species at the gorge were found in lower-gradient, deeper stream reaches (study areas) near the mainstem of the New River. These reaches provide stability and connectivity, which are crucial to fish in the flood- and drought-prone Appalachian region. The few fish found in headwaters were likely introduced by past “bait bucket” releases.

The Importance of Long-Term Data

Our results strongly suggest that New River Gorge and Delaware Water Gap are maintaining important stream habitats that provide vital refuge for at least 44 fish species. Although there are local areas of concern, these parks can serve as benchmarks for healthy stream fish communities for national parks throughout the mid-Atlantic region.

Our results strongly suggest that New River Gorge and Delaware Water Gap are maintaining important stream habitats that provide vital refuge for at least 44 fish species.

This research highlights the vital role of national parks in protecting native fish and their habitats. The study also underscores the necessity of long-term inventory and monitoring. Without it, we wouldn’t have had historical data to compare with our results. So we wouldn’t have known which species had or hadn’t declined in numbers. The stability of fish communities in these two parks is encouraging. But ongoing monitoring and active management are essential. They will help ensure that the parks continue to be sanctuaries for native freshwater fish, especially vulnerable species like the American eel.

"It’s incredible to now have this information about our tributaries,” said New River Gorge’s aquatic ecologist, Jennifer Flippin. “If you've been to the New River Gorge, you know we have steep terrain and data collection is not, in fact, a 'walk in the park.' We hope this is only the beginning of fisheries monitoring in our many tributaries, because it helps us focus our limited resources where they’re most needed."

About the author

Caleb J. Tzilkowski is an aquatic ecologist in the National Park Service, Eastern Rivers and Mountains Network (Inventory & Monitoring Division). Photo: NPS / Caleb Tzilkowski.

Cite this article

Tzilkowski, Caleb. 2025. “A Fish Study's Promising Results Highlight Parks' Role in Conservation.” Park Science 39 (2). August 29, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/psv39n2_a-fish-studys-promising-results-highlight-parks-role-in-conservation.htm