Last updated: February 2, 2022

Article

Pony Express Rider's Graze With Death

Public Domain

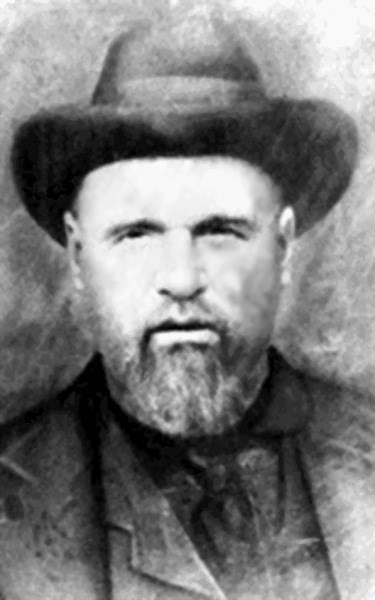

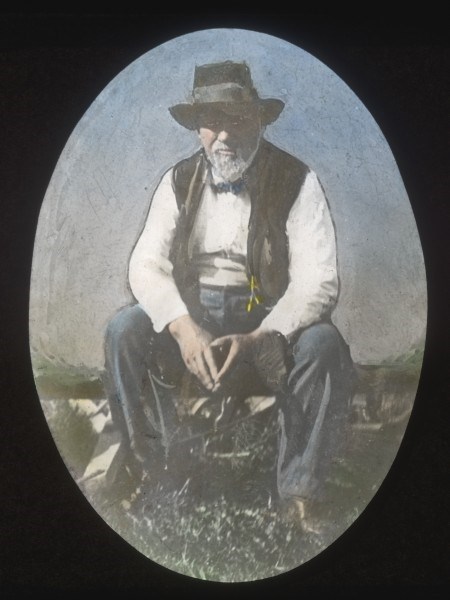

There are many unbelievable tall tales, and legends from the brave people who worked on the Pony Express. They rode day and night, rain, or shine, regardless of the known skirmishes with Native Americans across the trail's length. Some of the riders' stories are so inconceivable that they could not possibly have happened. How are we to know the facts from fiction? Historian Howard Driggs trusted Elijah Nicholas "Uncle Nick" Wilson as a primary source for the Pony Express experience. Wilson was born in April 1842 and had the exciting childhood of a pioneer living in the west. When he was about twelve years old, he decided to go live with the great chief of the Eastern Shoshone people, Washakie, and migrated across their territory for two years following the seasons.

When the Pony Express started hiring young riders, 18-year-old Wilson joined up. He had learned to break wild horses when he lived with the Shoshone, and he didn't shy away from a challenge. He figured joining the exciting new Pony Express was worth a shot. The work was exhausting, physically demanding, and dangerous, but Wilson said he got used to it after a while.

One outlandish event occurred on Wilson's way back from driving horses to Antelope Station in Nevada, through Superintendent Howard Egan's division of the Pony Express route. Wilson stopped at Spring Valley Station, where he was met by two orphaned boys who had been abandoned by the station manager to run the operation by themselves. They asked Wilson to stay for supper. After he let his horse out to graze, he noticed the horses going towards a patch of Cedar or pinion pine trees -- they were being driven away by two Indians, likely Paiutes or Shoshone. Guns blazing, Wilson sprinted towards the horses, trying to reach them before they were taken away. He fired three times at the men and missed. One of the raiders shot an arrow at Wilson, the flint-tipped arrow striking him two inches above his left eye. As the raiders rode off with the horses, the two boys reached Wilson and tried to yank the arrow from his forehead, but it wouldn't give. They broke off the shaft, leaving the flint tip buried in Wilson's forehead. The boys rolled him under the trees, thinking he was as good as dead. As Wilson lay unconscious, they ran for help at the next station. This is where some of the details of this story get a little hazy. It is not known for sure if the boys ran for help at Antelope Spring Station about 13 miles to the east, or if they ran to Schell Creek approximately 10 miles to the west.

They came back the next day with more men to help with Wilson's burial only to find him still alive! They carried Wilson back to the station and called for a doctor from Ruby Valley, 60 miles to the west, to treat the wounded and unconscious rider. Although the doctor was able to dig out the arrowhead, he didn't think the outlook was good. He prescribed the station boys to apply wet cloths onto Wilson's head, and he left. Six days into this treatment, Supt. Egan, happened by the station and saw Wilson unconscious but still alive! He sent for the doctor to come again from Ruby Valley and give further treatment. Wilson was unconscious for eighteen days. Once he awoke, he quickly recovered and returned to riding the dangerous express line.

NPS Map

Public Domain

Sources and Additional Information

Driggs, Howard R. “A Flint-Headed Arrow.” In The Pony Express Goes Through; an American Saga Told by Its Heroes, 70–78. New York, New York: Lippincott, 1963.

Wilson, Elijah Nicholas, and Howard R. Driggs. The White Indian Boy: The Story of Uncle Nick among the Shoshones. Salt Lake City, Utah: Paragon Press, 1991.

Bureau of Land Management. “Uncle Nick.” In The Pony Express in Nevada.