Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Podcast 084: Pig Skin and Wieners, the Early Influences on Preservation Architect Jack Pyburn

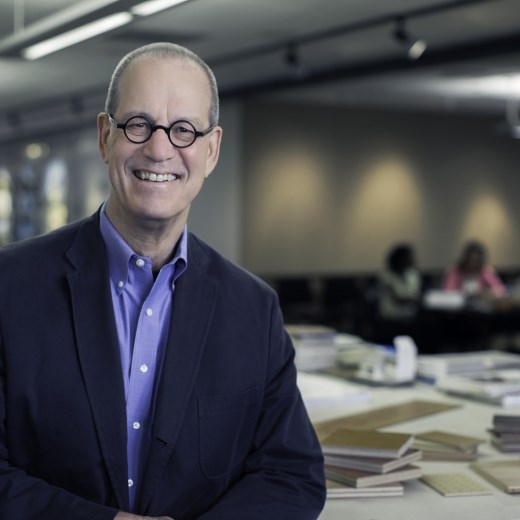

Lord, Aeck and Sargent

Football Career

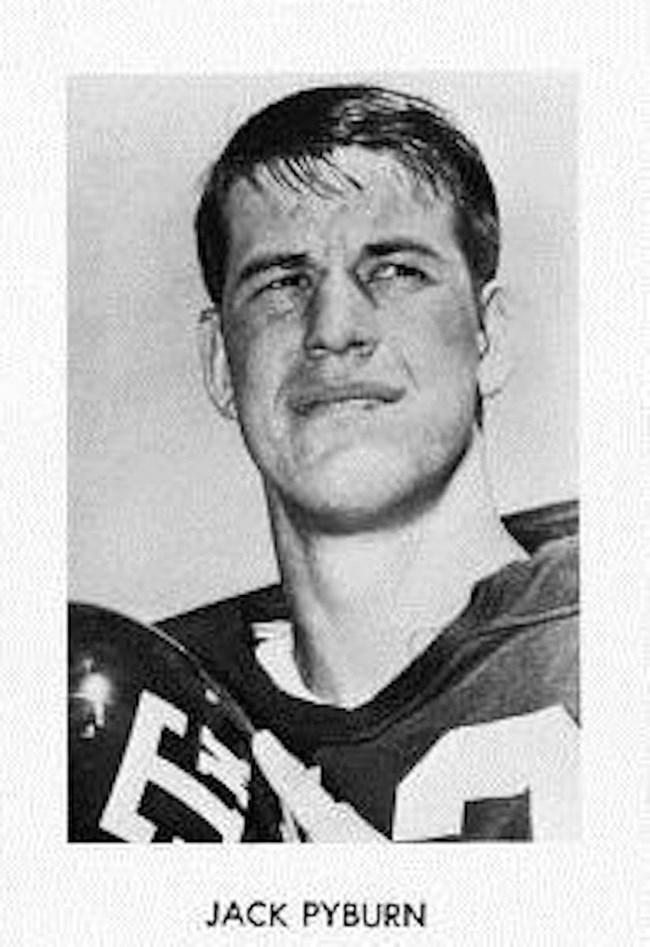

Jason Church: The first thing I want to ask you, Jack, I know you as a preservation architect, but I notice when I Google your name, that’s not what comes up first. It’s Jack Pyburn, football. Let’s just get that out of the way. I want to know why it comes up Jack Pyburn, football.

Jack Pyburn: Well, I grew up in Shreveport, Louisiana, not far from here. I went to Byrd High School in the class of 1963, which was one of only three high schools (two white and one African American) in Shreveport at the time. Byrd and Fair Park were the two white high schools. We played in the highest classification in the state, triple A at the time. I’m the youngest of four boys. My brothers ahead of me were athletes. I was the largest of all of them by a fair margin. It was just sort of assumed (by me) I was to participate in sports, and particularly in football, which I did.

I played football through high school, I did okay. I was not a great football player, but I did okay, partly because of my size. Actually, my favorite sport was track (throwing the discus). In fact, I competed here at Northwestern a number of times in high school and had good competitors from Natchitoches at the time. I broke the state discus record my junior year and again in my senior year. After my junior year, I really thought I would not play football anymore. I didn’t enjoy it that much, honestly. I loved track, it was something I got a lot of pleasure of and did okay at. I had a four year track scholarship offered at Tulane.

Come football season my senior year, and I said I wasn’t going to play my senior year because I wanted to focus on track, the head football coach, the only time he ever spoke to me, and certainly the only time he ever came to the house, came to my house and basically cajoled me into playing football my senior year in high school.

Again, I was not All-State, maybe All-City and District, but nothing particularly special. A&M football recruiters showed a tepid interest in me. However a local alum from A&M did, and I ended up taking a one year make good football scholarship to A&M and giving up a four year, full track scholarship to Tulane, which does not compute as rational thought, but it’s what happened.

Texas A&M University

Architecture

I got to A&M knowing I wanted to study architecture, I did all right my freshman year of football. It’s a mystery why I wanted to study architecture because I had no exposure to it in high school. The A&M athletic counselor tried to talk me out of architecture with the pitch that civil engineering was just like architecture. I spent a semester drawing nuts and bolts in civil engineering until I announced that was really not what I was interested in.

I made the A&M team, I got a full four year scholarship after my freshman year. My parents, my father in-particular had a policy that as a son, you worked your way through college. They did not pay for college for me or my brothers. All of us ended up going to college and as the youngest I am forever grateful for the guidance. I was basically working my way through school playing footballand had chosen architecture as my degree. Gene Stallings came from Alabama to A&M my junior year. He was a very demanding coach.

Architecture was a five year program before the four and two six year program was offered. Football was a four year eligibility. After the four years, I figured I was going to spend a year focused on my academics and low and behold, I got drafted by the Dolphins. I had no intention I was going to be drafted. I heard I was drafted on the radio. I decided to go try professional football, and if I made it, I figured the Dolphins would figure a way to get me into the reserves or differ my service. It was the height of the Vietnam War. If I made the team I would lose my deferment. If I was not back in school by September, I’d lose my deferment.

I made the team, the Dolphins did not have an alternative to the draft for me and, I was called up to the draft board in Shreveport for induction in December of my rookie year, 1967. For some unexplained way, I was deemed to be ineligible for service and thus Vietnam. As a result I, went back to play a second year of football in Miami. After my rookie season I went back to A&M for my first semester of my fifth year of architecture.

I played the second season and completed my second of my fifth year of architecture in the following spring. I graduated in 1969, and at that point I had enough football.. I told the Miami coach I was going to retire, so to speak (quitting was an ugly word)., Because I’d always been playing football, I figured I needed some experience in architecture. I had met an architect in my Miami barbershop so I asked him for a job. He gave me one to my surprise. It turned out his partner was Mark Hampton of the Sarasota School.

Texas A&M University

Balancing Demands

It was a very trying exercise to try to study architecture and play football under Gene Stallings. Probably not unlike trying to study architecture and play football for Nick Saban, but from an academic standpoint, he let me keep my scholarship the two spring semesters I needed to get my 5th year., In my sophomore year the dean of the School of Architecture, Ed Romieniec met me on the elevator, just he and I, and he told me I had to choose between football and architecture or he would. He ended up being a strong supporter after he knew I was seriously committed to architecture, and helped me through that last couple of semesters. I am forever grateful to Ed.

Miami was in its second year of existence my rookie year. The team had trained in Sarasota their first year. A bunch of folks from the circus that trained in Sarasota decided they were going to try out for football as a promotional or economic venture. One circus actor who tried out was a guy who had an act of doing wierd things with his bare feet. He like driving nails in boards with his bare feet. He decided he was going to enhance either his circus act or enhance his income by playing professional He was going to play football with no shoes on. It worked for his circus act, why not football?

Expansion teams, of which Miami was one, were made up of two groups. They were made up of rookies like me, just come out of college, wet behind the ears, and old veterans who were expendable at all the other established teams and thus available in an expansion draft. One of the guys in the expansion group, who had a very illustrious career but was on the downhill side of that career didn’t want anybody screwing around with the last remaining vestiges of his football career. The first play of the first practice, the veteran player broke the cricus actor’s foot and off we went. That’s an example of kind of the rag knot group we were. Miami was a very rag knot group at the time, and consequently we didn’t win any games, but I had a good time. I enjoyed photography, We would have sports news photographers traveled on the team plane. I got to be friends with the news photographers, particularly Jay Spencer who was the photographer for the Miami Hearld. He taught me a lot about photography

There were two treats from my friendship with Jay.. One of that was he would give me photos he took of play action where I was in the photo. The other treat was that he gave me camera equipment, well used camera equipment but bodies and lenses I would have never bought. I had a good time during the two years of pro football. I got to travel and see places and things that I had not been able to do as a kid. I got to see the major cities of the country that gave the the opportunity to see environments and buildings and environments I had studied.

Jason Church: When you started practicing architecture, what got you from architecture into preservation architecture?

Wiener Brothers

Preservation Architecture

Jack Pyburn: Well, I’ve thought about that. As I said a minute ago, I really did not have a lot of exposure to architecture. We were not a family who was artistic. We did a little bit of going to arts events, a symphony every once in a while. My mother did sew and taught me to sew. In retrospect, I think that was a formative aesthetic and building influence.

My dad was in the oil business. He was a drilling contractor in rural Louisiana. I spent a lot of my youth in rural Louisiana and east Texas. We were stoping at plantation stores. We were just going fishing and eating a can of Vienna sausage and some saltine crackers, and the plantation stores were the only place in the rural environment where one could get something to eat. I was exposed to the vernacular rural architecture that was formative as well. I love the rural context. I enjoy the innate intelligence of rural populations, it represents such talent and potential.

The other piece that exposed me to architecture was … the most underexposed modernist architect, Sam Wiener, whowas very active in Shreveport.

It is one of the amazing modernist architecture stories in the country, I think. I went to Broadmoor High School, I want to Youree Drive Junior High School and Arthur Circle School. I was the first class of those schools, those were all modern schools done by Wiener. My good friend lived next door to Sam Wiener’s modernist house on Longleaf Drive in Shreveport.. I got the newpapers for my morning paper route at Weiner’s sweeping modernist Big Chain Store.

I then went to architecture school, and modernism was what was taught. A&M’s pedagogy was a modernist Bauhaus education. I think all of those things infused me with architecture by osmosis In retrospect, the most telling early experience that suggested I would end up focused on preservation architecture was my terminal project, my fifth year project. I selected the Shreveport riverfront because of the historic buildings on the riverfront.

Wiener Brothers

At the time, Shreveport was planning the future of the Red River waterfront and conceiving a Parkway named for the mayor, Clyde Fant. Fant was my father’s Sunday School teacher. He gave me an inside look at the makings of a public project. I look back now and I realize my early exposure of existing, in fact, historic environments as a part of my early development.

I finished football and I didn’t have any experience working in an architect’s office. I thought I needed to find out what that was like and I went to work for Herb Johnson Associates in Miami who I met him at a barbershop. I told him I was looking for a job and he said, “Come on over.” His design director was Mark Hampton, who was a part of the Sarasota School and who had moved from Sarasota to Miami. Herb’s firm primarily did shopping center work. They designed the Bal Harbour Shops and Dadeland shopping center. It was a terrific opportunity to work with Mark Hampton, early in my career..

I worked for Herb for a year and then I thought I needed a different kind of experience so I went to what’s called a big E, little A, an engineering dominated firm with supporting architectural firm, Connell, Pierce, Garland and Friedman. CPGF had done a lot of work at Cape Kennedy. I found myself there in a strange but very interesting professional environment.

We had an amazing group of Cuban architects that had immigrated to Miami. We had Vincent Scully’s son, was a part of the firm. He was a young guy my age who they had hired, and a guy named Richard Lyons, whose father, Eric Lyons, was head of the RBIA, the Royal British Institute of Architects. We did things like enter the L’oeil competition in Paris. I mean, this was in this sort of nondescript engineering firm that these folks came together. I mean, it was just a fun time.

Then I knew I needed to go back to school. I mean, I had left a lot on the table in both football and architecture. I applied to Columbia, I applied to Washington University in St. Louis. It was, the Columbia program, Preservation program was brand new. I really had no exposure to preservation as such at that time, but Columbia had a good architectural program nonetheless. Probably would have found it if I had ended up going there.

I ended up going to Washington University, primarily for financial reasons, because they gave me support that I needed. I was married with a child by that time. I went to Washington, I got a degree in Urban Design. I actually practiced for a decade as a planner. Fortunately, I got registered. In Florida, you could get registered the year of experience, so I started taking the exam in Florida. Most states were three years at the time. I started taking the exam and got registered.

I was away from architecture for a decade doing community and preservation planning with an exceptional group of folks who had graduated from the Washington University Urban Design program ahead of me. The firm, Team Four, was multi-disciplinary with a focus on urban and community planning. I discovered preservation during that time. We did some very interesting work.

I then moved to Atlanta. Team Four was going to merge with the international planning and landscape firm, EDAW, now part of AECOM.EDAW, Eckbow, Dean, Austin, Williams was a modernist landscape firm from California. They had developed a strong national practice, and started to develop an international practice. They became very much an international force over time.

Team Four was going to merge with EDAW. Team Four was a top heavy (too many senior people for the size of the firm) small practice . Under the merger scheme, I was going to come to Atlanta to manage an office for EDAW. The merger fell through but my wife and I decided to come on to Atlanta. We came and I worked for EDAW for four years. After four years, I was ready to get back to architecture. Existing buildings and preservation was something I felt comfortable with, both structurally and architecturally

I evolved my preservation capability over time, starting small and building the knowledge and capability to do credible preservation work. I had my own practice for 25 years focused on preservation. In 2007 I was invited to to bring my practice into Lord, Aeck, Sargent’s preservation studio. LAS had a preservation practice, was a competitor and a group I respected for their preservation values.

Susan Turner and I shared the same values. She was the principal at LAS. We have about 15 people just focused on preservation work now.

Jason Church: I met you through a mutual friend, Tony Rajer and you had gotten involved with Pasaquan. Tell me a little bit, how did you get involved with Pasaquan, and your role there?

Jack Pyburn

Pasaquan

Jack Pyburn: Pasaquan was struggling, and it had a small Board. One of my acquaintances through the AIA in Atlanta was on the Board. The board knew they had stewardship of an important resource and needed to understand what was important about it. The site leadership was a doctor from Columbus, Georgia.Pasaquan was a folk art site developed by Eddie Owens Martin who went by the name of St. EOM.

He developed his family homesite in rural central Georgia into a mystical and surreal environment out of Sacrete, chicken wire and house paint. The figures he We developed a preservation plan thatset the foundation for treatment of the site. Ultimately the Kohler Foundation restored the site using the preservation plan and the property was transferred to Columbus (GA) State University for long term care and operation. This was a success story. I wish all resources of this quality could have a similar outcome.

Jason Church: Then did you ever do work with any of the other folk art sites?

Jack Pyburn: Yes. Paradise Garden.

Jason Church: Today, a little later today, we’re doing a webinar all about the preservation of African American historic sites. How did you get into that as sort of, I don’t want to say a focus, but you’ve definitely done a significant amount of work in that area.

Birmingham, Ala. Police Department Surveillance Files, 1947-1980. Collection 1125, Archives Department, Birmingham Public Library

Preservation Work on Historic African-American Sites

Jack Pyburn: Yes.The experience working on African American sites is personally the most rewarding preservation experience I have had or will have. I am thrilled that in my lifetime the breadth of African American history is starting to be give a central place in American history and the preservation of important African American resources is becoming a major focus of preservation investment. There is a ways to go in fully honoring the contribution of African Americans to our history but the movement is underway and there is momentum.

My involvement with the preservation of Africian American resources started with the Historic Structure Report here at Oakland Plantation for the Slave Cabins. In the analysis of the structures, one can physically come in contact with the humanity, courage, determination and intelligence of the African Americans who lived there. It was a very moving experience.

Then I had the opportunity to work on the Vulcan in Birmingham. Very quickly the place of African Americans in the history of the Vulcan became clear, both in terms of the role of African Americans in the steel industry in the late 19th, early first of half of the 20th century. As well as the position of African Americans in Birmingham relative to the Vulcan. They could only go up in the tower one day a week.

That got me involved in Birmingham, and so the opportunity to work on 16th Street Baptist Church came from that, recently the Civil Rights monument and the Gaston Motel, which is being restored. There’s a joint venture between the Park Service and the City of Birmingham, so we’re working on that, working on that right now.

Along the way, I had an opportunity to work on the Modjeska Simkins house in Columbia, South Carolina. A little vernacular structure, very central to Brown vs. Board of Education and the evolution of the legal foundation for that ruling. A variety of other sites like that. That part’s been …

Jason Church: Well, thank you for talking to us today, Jack.

Jack Pyburn: Yeah, you’re very welcome.

Jason Church: We look forward to having you at new conferences in the future and hearing about new projects you’re doing.

Jack Pyburn: Yeah, good, good. That’s great.

Jason Church: Really appreciate it.

Jack Pyburn: Yeah. Thank you.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.