Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Podcast 007: Using Lasers to Remove Graffiti from Rock Art and Rock Imagery

National Park Service

Jason Church: This is Jason Church. I am here interviewing Claire Dean of Dean & Associates Conservation Services. How are you doing today Claire?

Claire Dean: I am doing fine Jason how about yourself?

Jason Church: Very well! So Claire you are known for conserving rock art. Can you tell us what this is and a little bit about it?

Claire Dean: Sure. Rock art is the common term for paintings and carvings on rock and in North America that is mostly associated with native communities. I personally prefer to use the term rock imagery as it’s a little more neutral and I actually use that term at the request of elders Native American elders whom I work with who actually find the word some what offensive from their cultural stand point.

Claire Dean: So if you hear me refer to it as rock imagery that’s why and typically the other two terms you hear for it pictograph which are the painted sites and petroglyphs which are the ones that are carved into rock surfaces.

National Park Service

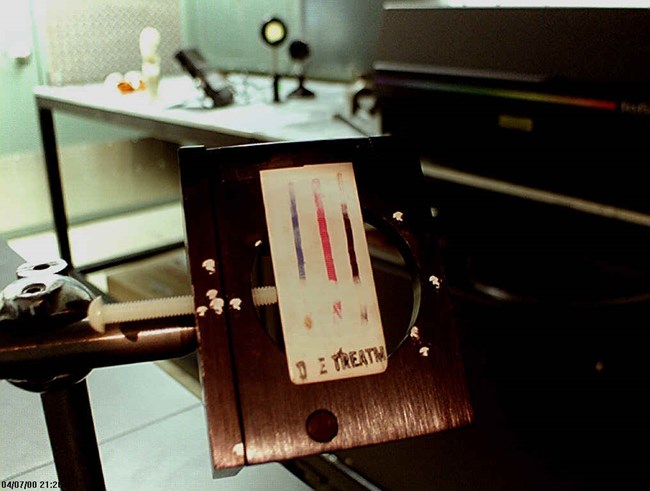

Jason Church: Very good. Well recently I know you did a project where you used a portable laser to remove graffiti off of rock imagery at Joshua Tree National Park. Can you tell us a little bit about this project and the use of lasers in conservation?

Claire Dean: The project at Joshua Tree is one that I have been working on for a couple of years and actually it was a two phase project initiated by the park. The first phase was to do a condition assessment of a series of sites within the boundaries of the monument. Not all of the rock out sites were looked at but a good number of them and from that assessment and working with the cultural resource manager Jan Keswick out there at Joshua Tree.

Claire Dean: We prioritized which ones would be looked at in phase two and also what we could do with the resources available under the contract for phase two. And we had one particular site that we decided to concentrate on which happens to be located within a camp ground and perhaps one of the most popular camp grounds in the park. And it is a small painted panel a pictograph that is located inside a small wind form alpa which is a little difficult to describe. But if you imagine a huge bolder with a big scoop taken out of the middle of it so that it looks like a half formed donut.

Claire Dean: The panel was inside the donut and this bolder is located smack between two camp sites at the level of the campsites and as the area is one that is frequented by recreational climbers actually inside the camp ground the reclining roots. This particular bolder gets a lot of visitation from folks who are not technical climbers but want to do a little bit of scrambling.

National Park Service

Claire Dean: Consequently we also have a lot of graffiti inside that bolder so that was the one that we decided concentrate our efforts on and the graffiti in there has been building up over many years and was mostly magic marker type inscriptions along with some paint and wax crayons and pencils and a little bit of charcoal. So we decided that that is the one that we concentrate on.

Claire Dean: I was adverse to using chemicals in that location for a number of reasons just overall for an environmental point of view. I prefer not to chemical cleaning has been typically the method used to remove graffiti at sites like this. The other reason for not wanting to use chemicals is that the alkaline is extremely small and close and without any type of ventilation and especially in the temperatures which we get out there in the desert there was an added issue of health in safety for people like myself and my assistant.

National Park Service

Claire Dean: So we decided to use lasers or at least to try at this site. Lasers have been used in art conservation for many years in fact back in Europe where I come from we were using them I think it is safe to say before North America was and mostly in architectural settings to clean off dirt and crusts related to air pollution on cathedrals and historic buildings.

Claire Dean: Lasers have had their limits until recently because of their size a portable laser a few years ago was typically the size of a small car and you could get them onto a big scaffold thing on a building but taking them out to other locations was really not feasible also because of the power needed to keep these puppies going that just wasn’t possible.

National Park Service

Claire Dean: Now laser technology has moved along and we have a lot of more portable units and more controllable ones including units that we can literally take out into the field. The camp ground at Joshua Tree is developed and as much as you can drive the truck into it in about fifty feet into the site but other places where we have taken laser we use rock image sites have involved having to pack it in a little distance but it is possible to do it with a team of people.

Claire Dean: So the potential for using lasers now is much greater and this is fantastic for people like myself that are working in areas that aren’t developed. Lasers typically are a much greener type of treatment. They really the main pollution they put out is the exhaust from the generator needed to power them.

Claire Dean: The laser that we were using at Joshua Tree can run off a four-hundred watt gasoline driven generator which if you got a good generator and you are maintaining it it is not putting out that much pollution probably less than your car. So the laser itself basically does not generate any pollution other than the material it is removing which of course burns but we are talking about something on a very very small level.

Jason Church: So on an environmental level the laser is a definitely a much greener version compared to the traditional chemical methods?

Claire Dean: Yes, absolutely.

Jason Church: How does it compare as far as removing the graffiti?

Claire Dean: In the work that I have been doing and I need to acknowledge not just the help of NCPTT with this but also Dr. Margaret Abraham who has been the recipient of a large research grant from NCPTT. And she and I also have another grant from NCPTT dealing with culturally appropriate treatment for rock image sites which lasers was one. So we have two NCPTT projects here that are joined at the hip.

Claire Dean: Now the grant that we received from NCPTT which actually was awarded to the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla one of the southern nations in Oregon. we were looking at trying to find culturally appropriate treatment for rock image sites and this is because many of the Native American groups that I work with including you are not happy from a cultural and spiritual stand point. They are not happy with the use of chemicals on rock image sites and sacred sites in general.

Claire Dean: We also have some pretty strict environmental legislation in Oregon too so that prohibit the use of chemicals. And chemical treatments have pretty much been the main ones up to date that have been used at rock image sites. We have done some microbration with some form of abrasive unit. Those are problematic you have to run a generator which you do with lasers. The abrasive unit is a dry system which we have to use two because we can’t soak these sites.

Claire Dean: Water can be a major issue for reasons of causing salt problems but also literally washing the site away. So we are using the dry system we don’t have the ability to abstract dust. So it becomes an extreme messy and dusty project. Collecting the dust on tops is not really very affective the wind blows it around. It works and it certainly has its place but microabrasion is not as green as you might think in the circumstances in which we have to use it.

National Park Service

Claire Dean: Chemical treatments has been the other one. Typically solvents using solvents to remove paints and other materials and usually applied in a gel form or as a poultice. These again have issues of course with giving off vapors into the air with disposal of the waste materials and also health and safety for the operators because we have to wear aspirators in the field because we don’t have installation.

Claire Dean: So and also a lot of the locations that I work in are extremely warm which means we have an issue with them evaporating to fast and it is very difficult to control that in the field. So looking for these alternatives to help us out was is very important but particularly for the Native American communities.

Claire Dean: Chemical treatments has been the other one. Typically solvents using solvents to remove paints and other materials and usually applied in a gel form or as a poultice. These again have issues of course with giving off vapors into the air with disposal of the waste materials and also health and safety for the operators because we have to wear aspirators in the field because we don’t have installation.

Claire Dean: So and also a lot of the locations that I work in are extremely warm which means we have an issue with them evaporating to fast and it is very difficult to control that in the field. So looking for these alternatives to help us out was is very important but particularly for the Native American communities.

National Park Service

Claire Dean: An elder who I work with regularly described it very sensitively she said how would you feel if I came into along and tipped paint stripper on your grandmother because that is exactly how they look at these sites. These sites are living places. They are not just lumps of rock with inscriptions on it.

Claire Dean: So the laser was one of the options we wanted to look at and the Native American community has been almost 100 percent positive in their reception of this. They like the concept that it is cleaning using light. They are very aware of the impact that ultraviolet light has on things outdoors and they could see a sort of direct connection between how light can get rid of paint and the everyday experiences. So we definitely have a lot of questions that are asked about the use of it.

Claire Dean: Megan and I have demonstrated the use of lasers to Native American communities on several occasions now. Only one of them has had its doubts but they weren’t completely negative. They were something they wanted to discuss and haven’t been discussing amongst themselves since. So it’s a for me it is a much cleaner alternative. It does a better job. It is more controllable. We don’t have the problems with bleeding of pigments and paints which we do when we use solvents for cleaning.

National Park Service

Claire Dean: While we can control that to a certain extent by our application method such as {unintelligible}. It is not that controllable especially in the field. So the laser takes care of that nicely and I also find that we have less residual staining. It is very difficult not to be left with residual staining when you chemically clean. Especially on particular surfaces that I deal with which are not dressed surfaces or finished surfaces they’re rough rock.

Claire Dean: The light emitted by a laser does seem to do some cleaning sub surface as well leaving us with less of a residue. So it has a lot of promise and we hope to be able to continue this and use it more extensively in the future.

Jason Church: Thanks Claire that answers a lot of questions I had about lasers and also chemical cleaning. So thank you very much.

Claire Dean: You are welcome anytime.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.

Tags

- joshua tree national park

- chemical cleaners

- chemical treatments

- claire dean

- conservation

- conservation services

- dean associates

- environmental conservation

- environmentally friendly

- jan keswick

- jason church

- joshua tree

- kevin ammons

- laser

- laser cleaning

- microabrasion

- native american

- ncptt

- petroglyph

- pictograph

- podcasts

- preservation

- ptt grant

- rock art

- rock image

- umatilla

- podcast

- preservation technology podcast