Last updated: April 26, 2021

Article

Pleistocene Life and Landscapes—Grand Canyon

NPS photo courtesy Robyn Henderek.

Rampart Cave

Article by Justin Tweet; Guest Scientist. National Park Service, Geologic Resources Division.

Rampart Cave in Grand Canyon National Park once contained one of the most unusual fossil deposits found in North America: a blanket of dung produced by Shasta ground sloths, Nothrotheriops shastensis. Shasta ground sloths are one of several species of now-extinct ground sloths that once roamed over much of North America. Although relatively small for ground sloths, these herbivores could still reach lengths of approximately 9 feet and weigh over 500 pounds. Their remains and dung have been found in several caves, but not to the extent known from Rampart Cave.

NPS photo, September 1938.

The National Park Service sent specialists including archaeologist Mark Raymond Harrington and geologist Edward Schenk to the cave in July 1936. Having previously worked at another sloth cave near Las Vegas, junior foreman Willis Evans recognized the significance of the site and brought it to the attention of Harrington and Schenk. Schenk conducted the first excavations, which produced hundreds of fossils. The largest excavation was conducted in 1942 under the supervision of Remington Kellogg of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History, although much of this material remains undescribed. Unfortunately, Rampart Cave was vulnerable to vandalism. Although the entrance was protected by a gate, in 1976 it was broken into, and a fire started that destroyed 70% of the dung deposits.

NPS photo courtesy Robyn Henderek.

NPS photo courtesy Robyn Henderek.

NPS photo, September 1938.

Rampart Cave is a moderately sized cave, with a roughly H-shaped floorplan. There are two narrow passages connected by a low broad chamber. One of the long narrow passages is approximately 140 feet long and the other, which opens to the outside, is about 155 feet long. Before the fire, the dung blanket averaged several feet thick throughout the cave, showing that Rampart Cave was utilized by sloths for an extended period of time. The dung deposit included several layers. The lowest, oldest layer was composed of sloth dung produced over thousands of years, from before 40,000 years ago to about 24,000 years before present ("before present" refers to 1950, accepted as the standard "present" for radiocarbon dating). Above this was a "seam" of plant material about 13 inches thick left by packrats. The rest of the deposit was made up of sloth dung produced between about 13,000 and 11,000 years before present. The "seam" correlates to the height of the most recent ice age, suggesting that sloths left the area at that time. Additional isolated fossil packrat middens (remnants of packrat dwellings of plant debris and other material cemented by packrat urine) and deposits of bat guano have also been found throughout.

Photo by Michael Bobko.

Plant fossils in the sloth dung and packrat middens provide important information about the ecosystem and climate of the Rampart Cave area over thousands of years and a switch from a building ice age to a warmer and drier interglacial period. The sloth dung shows that the animals ate a variety of desert plants, including desert globemallow, Nevada mormontea, saltbush, catclaw acacia, cacti, reeds, and yucca. It has been suggested that this diet is evidence that sloth extinction is related to overhunting and not climate change, because these kinds of plants were doing well at the time the sloths went extinct. In addition to the plant fossils, at least one piece of sloth dung was found to contain roundworms and their eggs.

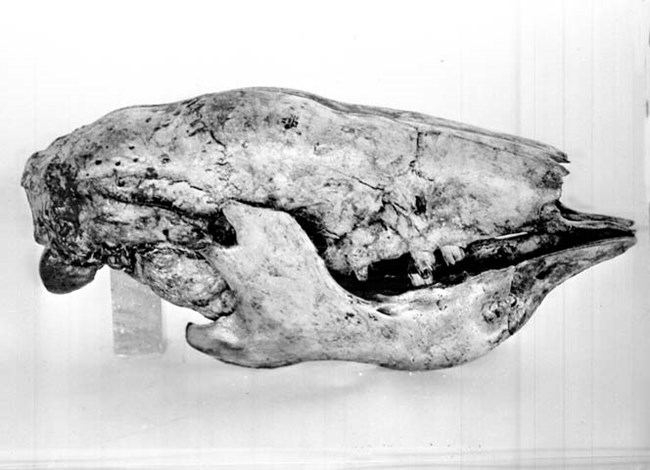

NPS photo, September 1936.

Body fossils found in Rampart Cave include not only bones, but also hair, skin, sinew, and other soft parts, mostly of sloths. The relative abundance of the bones of young sloths suggests that the cave was used as a shelter or nursery for the young.

Although sloths are by far the most abundant animals represented in the cave, a wide variety of other animals are also known. They include tortoises, lizards, snakes, herons, vultures, condors, hawks, eagles, owls, falcons, rodents, rabbits, bats, bobcats, mountain lions, ringtails, weasels, skunks, horses, mountain goats, and bighorn sheep. One of the more unusual specimens is a goat forefoot with preserved muscle, cartilage, and skin. Unlike many of the other caves in the Grand Canyon region, there does not appear to evidence for human occupation or usage. Aside from the sloths, extinct animals known from the cave include a vampire bat, North American horses, and an extinct species of mountain goats.

By FunkMonk (Michael B. H.); Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Grand Canyon National Park

Grand Canyon National Park, a World Heritage Site, encompasses 1,218,375 acres and lies on the Colorado Plateau in northwestern Arizona. The land is semi-arid and consists of raised plateaus and structural basins typical of the southwestern United States. Drainage systems have cut deeply through the rock, forming numerous steep-walled canyons. Forests are found at higher elevations, while the lower elevations are made up of a series of desert basins.

NPS photo, September 1936.

Well known for its geologic significance, the Grand Canyon is one of the most studied geologic landscapes in the world. It offers an excellent record of three of the four eras of geological time, a rich and diverse fossil record, a vast array of geologic features and rock types, and numerous caves containing extensive and significant geological, paleontological, archeological and biological resources. It is considered one of the finest examples of arid-land erosion in the world. The Canyon, incised by the Colorado River, is immense, averaging 4,000 feet deep for its entire 277 miles. It is 6,000 feet deep at its deepest point and 18 miles at its widest.

Related Links

- Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona—[Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home]

- National Fossil Day

- NPS—Fossils and Paleontology

- Cave Paleontology

- Fossils through Geologic Time—Cenozoic Era

- NPS—Caves and Karst