Last updated: June 14, 2023

Article

Plague

(This page is part of a series. For information on other illnesses that can affect NPS employees, volunteers, commercial use providers, and visitors, please see the NPS A–Z Health Topics index.)

CDC

Plague is a non-native, infectious disease caused by the bacterium Yernia pestis, which is generally spread by fleas from infected rodents to other mammals, including humans. Plague is the cause of the “Black Death,” which caused millions of deaths during the Middle Ages. Plague was introduced to the United States in 1900 by rats arriving on steamships.

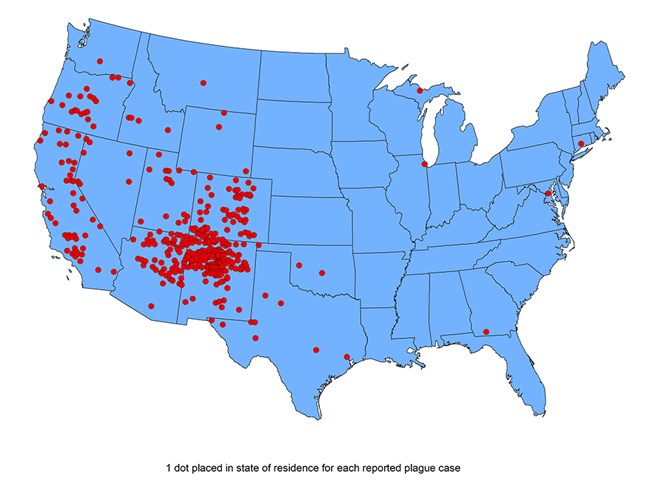

Humans: Most U.S. human cases occur in the western United States, with an average of 7 cases reported each year. Humans can become sick when the plague bacteria are transmitted through the bite of an infected flea, through direct contact with contaminated fluid or tissue, or through breathing infectious droplets. The symptoms vary, depend on how the bacteria entered the body, and can include fever, headache, weakness, abdominal pain, swollen, painful lymph nodes near the site of the flea bite, rapidly developing pneumonia, and shock. Symptoms can develop 2–8 days after exposure. Infections can be fatal without early antibiotic treatment. Post-exposure prophylaxis is also indicated for persons with known exposure to plague. However, there is currently no human plague vaccine available in the United States.

Animals: Plague has had significant impacts on some wildlife populations, causing large die-offs or even local extinction. Many parks in the western U.S. have been impacted by plague. In parks in the west, rodents most often affected include squirrels, chipmunks, woodrats, and prairie dogs. When animals die from plague, their fleas look for new hosts, thereby spreading disease and increasing risk to humans. By protecting wildlife from plague, we can help protect ourselves.

Environment: Yersinia pestis is easily destroyed by sunlight and drying. When released into air, the bacterium can survive for up to one hour.

PREVENTION

- View animals in the wild from a safe distance. Never approach or touch wildlife.

- Keep pets leashed and up-to-date on flea and tick prevention.

- Stay on the trail and avoid contact with rodent burrows.

- Reduce exposure to rodents by eliminating sources of food and nesting places around buildings, removing brush, rock piles, firewood, and food supplies around living areas, and excluding rodents from buildings (see NPS Rodent Exclusion Manual in Resource section below).

- Use insect repellent if you think you could be exposed to fleas during activities such as camping, hiking, or working outdoors. Products containing DEET can be applied to the skin as well as clothing, and products containing permethrin can be applied to clothing. Follow instructions on the label.

- NPS employees,

- During a plague outbreak among wildlife,

- Discuss the situation with IPM. Environmental treatment with insecticides to kill fleas can be effective in the immediate area of an outbreak, but the effects are short-lived.

- Consider wildlife vaccination. Vaccines have been successfully used for some wildlife and can provide long-term protection.

- Consider closure of certain parts of the park based on an assessment of risk.

- Always follow safe work practices (see USGS Safe Work Practices for Working with Wildlife in Resources section below).

- During a plague outbreak among wildlife,

- If you become ill following a potential exposure, contact your healthcare provider and let them know of your concern. Also, please report any confirmed illnesses to the NPs Office of Public Health (publichealthprogram@nps.gov) as directed in the “Disease Reporting” guidance below.

- Report concerns about sick or dead wildlife to the park resource manager and the Wildlife Health Branch at npsdiagnostics@nps.gov.

- NPS IPM Indoor Rodent Management for NPS Properties (restricted access)

- NPS Rodent Exclusion Manual (2014)

- NPS Rodent Exclusion Video (2017) (restricted access)

- NPS Proper Use and Placement of Snap Traps

- NPS Integrated Pest Management: Rodent Management (restricted access)

- Hammond TT, Liebman KA, Payne R, Pigage HK, Padgett KA. Plague Epizootic Dynamics in Chipmunk Fleas, Sierra Nevada Mountains, California, USA, 2013-2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(4):801-804. doi:10.3201/eid2604.190733

- Mize EL, Britten HB. Detections of Yersinia pestis East of the Known Distribution of Active Plague in the United States. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2016;16(2):88-95. doi:10.1089/vbz.2015.1825

- Danforth M, Novak M, Petersen J, et al. Investigation of and Response to 2 Plague Cases, Yosemite National Park, California, USA, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(12):2045-2053. doi:10.3201/eid2212.160560

- Bosch SA, Musgrave K, Wong D. Zoonotic disease risk and prevention practices among biologists and other wildlife workers--results from a national survey, US National Park Service, 2009. J Wildl Dis. 2013;49(3):475-585. doi:10.7589/2012-06-173

- Fleer KA, Foley P, Calder L, Foley JE. Arthropod vectors and vector-borne bacterial pathogens in Yosemite National Park. J Med Entomol. 2011;48(1):101-110. doi:10.1603/me10040

- Wong D, Wild MA, Walburger MA, et al. Primary pneumonic plague contracted from a mountain lion carcass. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(3):e33-38. doi:10.1086/600818

- Gese EM, Schultz RD, Johnson MR, Williams ES, Crabtree RL, Ruff RL. Serological survey for diseases in free-ranging coyotes (Canis latrans) in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. J Wildl Dis. 1997;33(1):47-56. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-33.1.47

- Clover JR, Hofstra TD, Kuluris BG, et al. Serologic evidence of Yersinia pestis infection in small mammals and bears from a temperate rainforest of north coastal California. J Wildl Dis. 1989;25(1):52-60. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-25.1.52