Last updated: April 17, 2024

Article

Places of WWII History in Evansville, IN

Courtesy of University of Southern Indiana, Rice Library Digital Collections, https://rightsstatements.org/page/InC-NC/1.0/?language=en

World War II transformed Evansville. Located just north of the Ohio River in southwestern Indiana, Evansville’s inland location was perfect for large-scale defense production. Seventy-five percent of the city’s factories received military contracts and converted to wartime production, drawing federal funding and workers into the city. From 1940 to the middle of the war, employment surged from 18,000 to 60,000 jobs. The overall population rose to 150,000. While Evansville saw an influx of 25,000 permanent residents, new job opportunities also opened for women and African Americans. By 1944, Vanderburgh County (including Evansville) had received $580 million in defense contracts, more than any other county in southern Indiana and the fourth highest in the state.

To commemorate Evansville’s wartime history, the Secretary of the Interior designated Evansville an American World War II Heritage City in 2022. This article explores some of the many places and stories associated with Evansville’s contributions to the war effort.

Courtesy of University of Southern Indiana, Rice Library Digital Collections, https://rightsstatements.org/page/InC-NC/1.0/?language=en

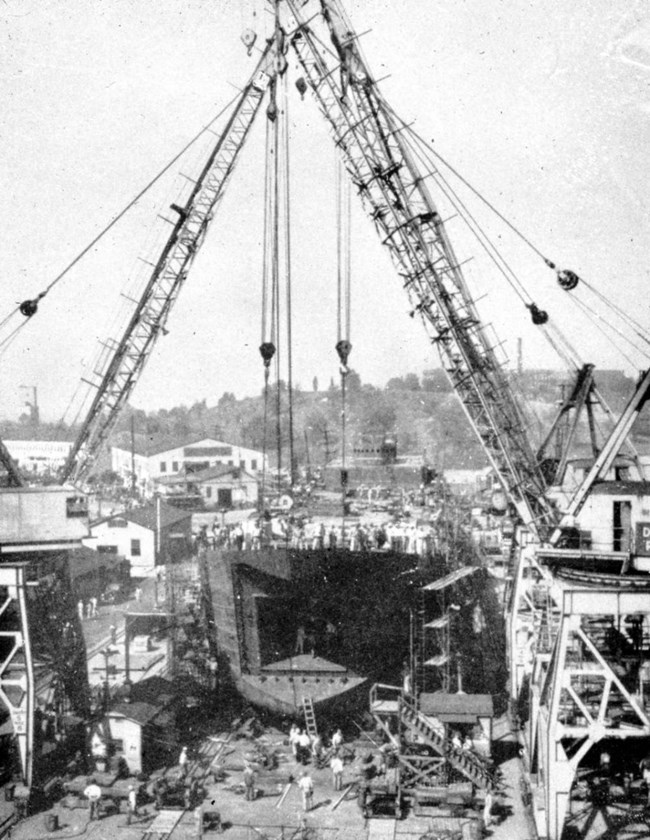

Evansville Shipyard

During World War II, Evansville became home to the “world’s largest inland producer of ocean-going ships.”[1] The Navy built Evansville Shipyard on 40 acres of land on the city’s west side. Within four months after the plant was first announced in February 1942, the Missouri Valley Bridge and Iron Company began production on Evansville Shipyard’s first landing ship tank (LST). LSTs were used to deliver military vehicles, troops, and supplies directly on shore. They made it possible to launch amphibious attacks and deliver cargo without relying on piers or docks at ports. Perhaps most famously, LSTs were used as part of the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944, also known as D-Day.

By February 1945, Evansville Shipyard produced 167 LSTs. By working around the clock in shifts, workers produced one ship every four days in 1944. With each ship measuring 300 feet long by 50 feet wide, this was no small feat. Shipyard workers also built 13 ammunition lighters and 17 oceangoing barges.

In addition to providing jobs and income, Evansville Shipyard brought the community together. When ships were launched, guests could attend if they had an invitation. Even without an invitation, residents still found ways to watch launches by gathering along the levee at Sunset Park, Dress Plaza, and on rooftops. The last ship was launched from Evansville Shipyard on December 12, 1945.

In January 1946, a fire destroyed Evansville Shipyard. The city continues to commemorate its shipbuilding history aboard the USS LST-325, the only operational LST in WWII configuration afloat in US waters. USS LST-325 was listed in the National Register of Historic Places on June 24, 2009 and serves as the home of the USS LST Ship Memorial.

Courtesy of University of Southern Indiana, Rice Library Digital Collections, https://rightsstatements.org/page/InC-NC/1.0/?language=en

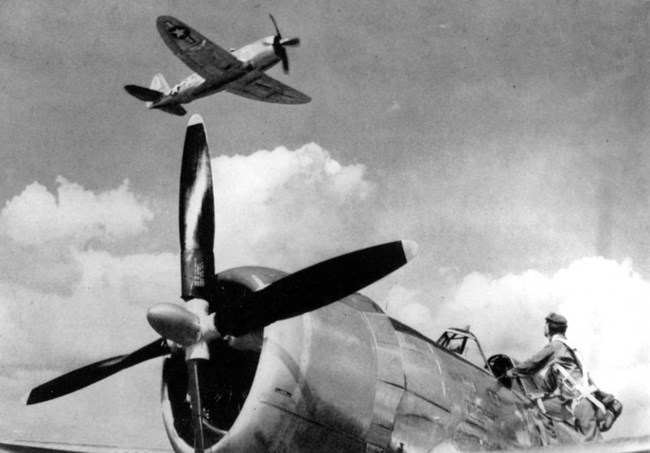

Republic Aviation

The war also brought new companies to Evansville. In March 1942, Republic Aviation Corporation announced plans to build a new aircraft facility on the city’s northside. The undertaking was massive, spanning 972,909 square feet on 71 total acres of land. The project broke ground nine months early in April 1942.

Republic Aviation primarily produced P-47 Thunderbolts, aircraft that were used as fighter planes and bomb escorts. A single plane weighed almost seven tons with wings that spanned almost 41 feet, and a nose to tail length of 36 feet. Over the course of the war, Republic Aviation and two other factories produced 15,683 total P-47 Thunderbolts between May 1941 and December 1945. Republic Aviation’s Evansville plant produced 6,242 of them.

Courtesy of University of Southern Indiana, Rice Library Digital Collections, https://rightsstatements.org/page/InC-NC/1.0/?language=en

When production began, the company hired 5,000 people. About half of them were women. Before the war, women comprised only 15% of all factory workers in Evansville. But as men departed for military service and defense production took off, this number increased to 40%.

After the war, International Harvester bought the former Republic Aviation plant and used it to produce refrigerators. The facility was later purchased by Whirlpool Corporation. The Indiana Historical Bureau, Vanderburgh County Historical Society, and Whirlpool Corporation erected a historical marker for the P-47 Thunderbolt Factory in 1995.

Courtesy of University of Southern Indiana, Rice Library Digital Collections, https://rightsstatements.org/page/InC-NC/1.0/?language=en

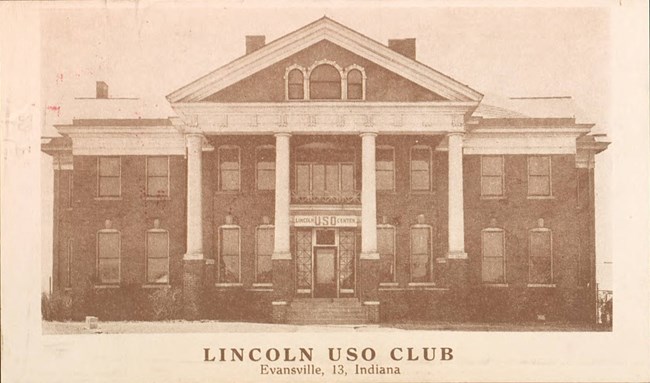

Lincoln USO Club

Despite segregation, Black residents of Evansville created a thriving community, which centered around the Lincoln Gardens development after 1938. Lincoln Gardens was a low-cost modern housing project managed by and for African Americans. To celebrate this New Deal project, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt attended its dedication.

After the US entered World War II, residents established a United Service Organization (USO) club on Main Street for servicemen from nearby Camp Breckenridge. The club welcomed white soldiers but denied access to African Americans. Although official USO policy forbade discrimination based on race or religion, it proved difficult to enforce in many communities.

To provide a place for Black servicemen to relax and socialize in Evansville, African American residents organized a Volunteer Service Club (VSC) at Lincoln Gardens. The VSC opened in October 1942 and hosted events such as donation drives and dances. Local women organized scrap drives, sold war stamps, and prepared home cooked meals at the VSC, while others interviewed for the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps.

Courtesy of the University of Minnesota Libraries, Kautz Family YMCA Archives

In January 1943, an official USO club for African Americans was established at a former orphanage down the street from Lincoln Gardens. Known as the Lincoln USO Club, the facility provided Black servicemen with somewhere to sleep and shower. It also included rooms for reading, writing letters, and playing games such as cards, table tennis, and billiards.

On the weekends, regular events included dances on Saturday nights and breakfasts on Sunday mornings. The Lincoln USO also served as a job placement center with programs to train African American men and women for defense jobs at local industrial plants. After the war, the Lincoln USO Club continued to serve as a community center. In the early 1970s, it was vacated and razed due to a fire.

By the 1990s, the Lincoln Gardens Housing Project had deteriorated and almost all its buildings were demolished. The last remaining apartment building now serves as the Evansville African American Museum. In 2020, the Indiana Historical Bureau erected a historical marker to recognize the history of Lincoln Gardens.

Courtesy of University of Southern Indiana, Rice Library Digital Collections, https://rightsstatements.org/page/InC-NC/1.0/?language=en

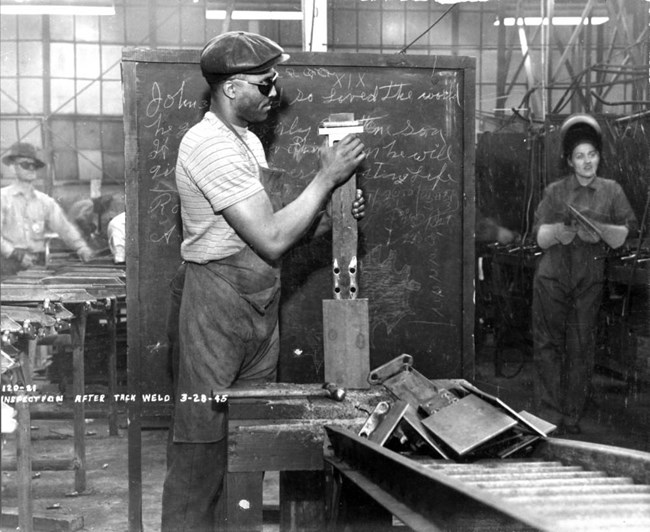

Evansville Ordnance Plant

Chrysler received one of Evansville’s largest defense contracts and became the Evansville Ordnance Plant. Over the course of the war, the plant produced over 3 billion rounds of .45 caliber ammunition. This was equivalent to 96% of the total quantity used by the military and other defense contracts. At the plant, women workers assembled wire harnesses and packed ammunition, while men repaired parts of tanks and operated heavy machinery. Although the plant’s success relied on contributions from both Black and white men and women, some white workers resisted an integrated workplace.

In September 1943, white workers went on strike after management assigned African Americans to work with them. Over four days, the strike ground the department to a halt until union and management representatives negotiated an agreement.In addition to the racial prejudice among white workers, hostility between Chrysler and the union contributed to the strike. When the plant began to transition to war production in January 1942, Chrysler brought on 5,000 new workers to manufacture ammunition and plane parts. According to the union, the company had a policy to refuse African Americans for jobs. Believing that Chrysler should hire regardless of race, union leadership asked the War Manpower Commission for help.[2]

Courtesy of University of Southern Indiana, Rice Library Digital Collections, https://rightsstatements.org/page/InC-NC/1.0/?language=en

After a series of meetings, Chrysler reluctantly agreed not to discriminate based on race, color, or creed in hiring or in pay. The company hired Black workers in three different departments, but the trouble was far from over. According to Pat Ross, the Local 705 president, both Black and white workers expressed that “due to Evansville’s proximity to the South, segregation would be the best policy.”[3] When the strike finally broke out over the attempted integration, the union blamed Chrysler for intentionally trying to aggravate racial tensions and delegitimize the union. Meanwhile, Chrysler accused the union of trying to maintain segregation and keep white and Black workers separate.

Although World War II created new opportunities for African Americans in military and civilian service, the US was still a long way off from racial equality. Experiences like the Evansville Ordnance Plant strike and the segregation in the US military frustrated African Americans. Some spoke out and channeled their discontent into the Double V campaign and political activism, strengthening the coming groundswell of the modern civil rights movement.

The Evansville Chrysler plant closed in 1959. Some of the buildings are still standing.

This article was researched and written by Jade Ryerson, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education, and funded by the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the NPS.

[1] Lisa Wiesjahn, Bill Fluty, and Patrick W. Wathen, “City did bit for war effort,” Evansville Courier and Press, August 18, 1995, https://www.newspapers.com/article/evansville-courier-and-press-city-did-bi/127540301/.

[2] Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Executive Order 9139: Establishing the War Manpower Commission,” The American Presidency Project, UC Santa Barbara, April 18, 1942, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/executive-order-9139-establishing-the-war-manpower-commission. During the war, the War Manpower Commission was a federal agency tasked with “the most effective mobilization and maximum utilization” of the labor force among the military, agricultural sector, and civilian industries.

[3] “Colored Gets Transfers; 2000 Whites Go on Strike in Protest,” Evansville Argus, October 1, 1943, The Evansville Argus Newspaper (1943-10-01) - Local Newspapers and Newspaper Photographers Collection - Rice Library Digital Collections (usi.edu).

Brauer, Emma and Robin Johnson. “Lincoln Gardens.” Digital Civil Rights Museum. Ball State University. Accessed July 3, 2023. https://www.digitalresearch.bsu.edu/digitalcivilrightsmuseum/items/show/56.

Evansville Argus. “Colored Gets Transfers; 2000 Whites Go on Strike in Protest.” October 1, 1943. https://digitalarchives.usi.edu/digital/collection/Argus/id/1788/rec/1.

Evansville Argus. “Local Plants Get War Orders; To Hire 15,000: NAACP to Seek Openings for Race Workers.” January 24, 1942. https://digitalarchives.usi.edu/digital/collection/Argus/id/1365/rec/9.

Evansville Argus. “Public Is Asked to Donate Games, Money, and Service to Help Operate Center.” November 14, 1942. https://digitalarchives.usi.edu/digital/collection/Argus/id/1451/rec/1.

Evansville Argus. “U.S.O. Center to be Located in Guardian Building on Lincoln.” September 5, 1942. https://digitalarchives.usi.edu/digital/collection/Argus/id/1595/rec/3.

Indiana Historical Bureau. “P-47 Thunderbolt Factory.” The Indiana Historian (June 1998): 11. https://www.in.gov/history/files/aviationinindiana.pdf.

Indiana Historical Bureau. “P-47 Thunderbolt Factory Marker Text Review Report.” 82.1995. July 8, 2013. https://www.in.gov/history/files/P-47-Review-FINAL.pdf.

Indiana Historical Bureau. “We Don’t Intend to Fall in Anymore at the End of the Parade.” The Indiana Historian. February 1995. https://secure.in.gov/history/files/7030.pdf.

Johnson, Sydney. “How the USO Served a Racially Segregated Military Throughout World War II.” USO. February 7, 2022. https://www.uso.org/stories/3001-how-the-uso-served-a-racially-segregated-military-throughout-world-war-ii.

Madison, James H. and Lee Ann Sandweiss. “The Great Depression and World War II.” Chap. 9 in Hoosiers and the American Story, 229-259. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press, 2014. https://indianahistory.org/wp-content/uploads/Hoosiers-and-the-American-Story-ch-09.pdf.

Wathen, Patrick. “The Evansville Shipyard.” Evansville Courier and Press. December 5, 1981. https://www.newspapers.com/article/evansville-courier-and-press-the-evansvi/127540668/.

Wiesjahn, Lisa, Bill Fluty, and Patrick W. Wathen. “City did bit for war effort.” Evansville Courier and Press. August 18, 1995. https://www.newspapers.com/article/evansville-courier-and-press-city-did-bi/127540301/.

Tags

- world war ii

- wwii

- ww2

- awwiihc

- evansville

- indiana

- military and wartime history

- african american history

- african american history and culture

- black history

- wwii aah

- defense production

- uso

- women's history

- labor history

- civil rights

- places of article

- american world war ii heritage city program

- world war ii home front