Last updated: October 19, 2021

Article

Places of Women and Vegetarianism

"Pound for pound, Brussel sprouts equal beef." --Alvenia Fulton

Vegetarianism is ancient. Before European contact, many of the Indigenous tribes of North America ate little meat, instead placing crops like corn, beans, squash, and fruit at the center of their diets. Many people on the Indian subcontinent have abstained from meat for religious reasons since as early as the 6th century BCE.

In the modern United States, people have advocated for vegetarianism for reasons related to religion, health, and animal rights. Women have played a large role in this movement. They have often connected it to other movements like temperance, suffrage, and civil rights.

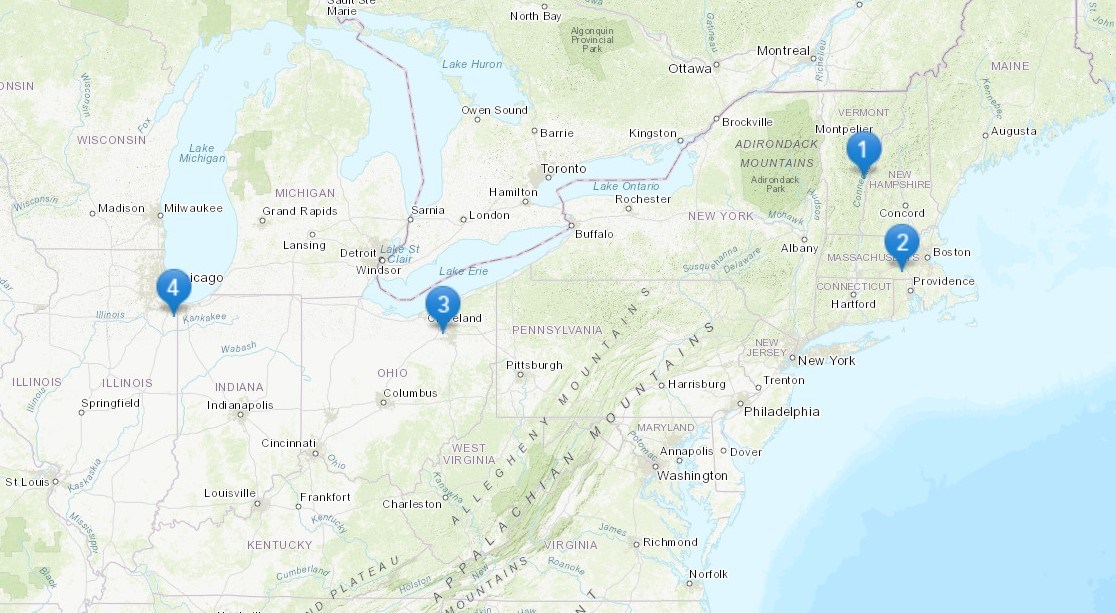

Explore a few of the places of associated with women and vegetarianism.

Photo by dougtone. CC BY-SA 2.0.

1. Congregational Church of Chelsea

Social reformer Asenath Hatch Nicholson (1792-1855) attended this church in her hometown of Chelsea, Vermont in the early 1800s. Nicholson is best known as a chronicler of the Great Famine in Ireland. But she also published what was probably the U.S.’s first vegetarian cookbook, Nature’s Own Book.

Nicholson learned about vegetarianism at a lecture by Sylvester Graham, a temperance and vegetarian advocate whose teachings inspired the graham cracker. Nicholson and her husband opened a vegetarian boarding house in New York City. Nature’s Own Book came out in 1835, and Nicholson followed it up with A Treatise on Vegetable Diet (1848), which left eggs and butter out of the recipes.

The Congregational Church of Chelsea was built between 1811 and 1813. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

Photo by victorgrigas. CC BY-SA 3.0.

2. Fruitlands

Fruitlands was a short-lived utopian Transcendentalist commune in rural Massachusetts. Amos Bronson Alcott, the father of author Louisa May Alcott, and Charles Lane founded the site in 1843. The two men envisioned Fruitlands as a place where people could remove themselves from the economy and the larger society and pursue enlightenment. They connected bodily purity with spiritual growth.

Residents at Fruitlands followed a vegan diet. While vegetarians avoid eating meat, vegans cut out all animal products, including dairy and eggs. Coffee, tea, and alcohol were banned. Vegetables that grew underground, like potatoes and carrots, were not allowed because Alcott and Lane thought they showed a “low nature.” Fruitlands members did not wear cotton because it was produced by enslaved people. They believed that wearing wool or using animals for farm labor was exploitation.

Unfortunately, the male residents of Fruitlands preferred philosophy to farm labor. Alcott’s wife Abigail May Alcott complained in her journal that her husband and Lane “spare the cattle, but they forget the women and children.” Her daughter Louisa May Alcott’s 1873 story Transcendental Wild Oats satirized the commune and portrayed Abigail May as performing all the real labor and childcare:

“About the time the grain was ready to house, some call of the Oversoul wafted all the men away. An easterly storm was coming up and the yellow stacks were sure to be ruined. ... The indomitable woman got in the grain and saved food for her young, with the instinct and energy of a mother-bird with a brood of hungry nestlings to feed.”

The community could not produce enough food to sustain itself through the winter. It disbanded in December 1843, after only seven months.

The original farmhouse at Fruitlands was designated a National Historic Landmark on May 30, 1974.

Photo by Ohio Office of Redevelopment, CC BY 2.0.

3. Cleveland Athletic Club

Minta Asha Philips Beach (also known as Mrs. David Beach) was a suffragist and vegetarian. She filled the headlines of 1912 when she walked 1071 miles from New York to Chicago. She wasn’t the first to complete this feat, but she was the first woman to do so on an entirely vegetarian, raw food diet. It took her 42.5 days. Beach was determined to show that a vegetarian diet was healthy and that women were capable of strenuous physical exercise.

The “vegetarian pedestrian” received considerable press coverage. One Chicago newspaper described her typical travel lunch of “one orange; two grated apples; some ground wheat and a glass of milk.” Dinner was “lettuce salad; glass of milk into which had been beaten two eggs…with the juice of a lemon and a little salt; two ripe bananas mashed with a fork…and mixed with lemon juice and cream.”

Beach wasn’t the only suffragist-vegetarian. Some British activists linked the oppression of women to the exploitation of animals. The Women’s Freedom League, a British suffragist organization, had a vegetarian restaurant called the Minerva Café in its headquarters building.

Minta Beach stayed at the Cleveland Athletic Club while passing through the city. She gave a speech to the club’s members on the benefits of eating vegetarian. The club’s building is a contributing property to the Euclid Avenue Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2002.

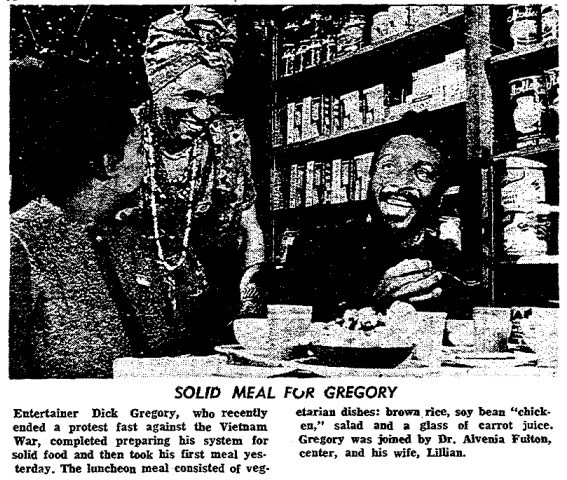

Chicago Defender, January 10, 1968.

4. Site of Fultonia Health Food Center

Dr. Alvenia Fulton was a nutritionist, businesswoman, and vegetarian. She opened one of the country’s first Black-owned health food stores. Born in Tennessee, she moved to Chicago in the 1950s. Fulton had previously suffered from ulcers. She credited her recovery to drinking juices made from raw fruits and vegetables. At her store, Fultonia Health Food Center, she sold juices and vegetarian meals and touted the benefits of fasting and avoiding meat.

In the 1960s, Fulton befriended the comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory. Gregory was a vegetarian who saw the exploitation of animals as another type of injustice to be opposed. He also became well known for going on hunger strikes to protest racism and the Vietnam War. Fulton consulted and often joined him during these fasts. In January 1968, the Chicago Defender reported that Gregory had ended a 54-day hunger strike at with a meal of soy “chicken,” carrot juice, brown rice, and salad at Fultonia’s. The store “smelled of healthful foods, dominated by herbs and the omnipresent soy bean—the vegetarian’s staple. Colorful cans of coconut meal, Graham crackers, brown sugar, yeast and wheat germ sparkled on neat shelves.” Fulton explained that “pound for pound, Brussel sprouts equal beef.”

Fulton wrote a column in the Defender, hosted a radio show about healthy eating, and penned books about fasting and vegetarianism. Her store became a destination for celebrities interested in her diet advice, including Mahalia Jackson and Muhammad Ali. She died in 1999.

Fultonia Health Food Center was located at 521 E. 63rd St., in the Woodlawn neighborhood of Chicago. Chicago is a Certified Local Government.

Bibliography

Alcott, Louisa May. "Transcendental Wild Oats," 1873. https://public.wsu.edu/~campbelld/engl368/transoats.pdf

Ewbank, Anne. "How Vegetarian Food Fueled the British Suffragette Movement," Atlas Obscura, July 3, 2018. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/what-did-british-suffragettes-eat

Francis, Richard. Fruitlands: The Alcott Family and Their Search for Utopia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011.

Hankins, Barry. The Second Great Awakening and the Transcendentalists. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004.

“I’m Walking 1000 Miles on Raw Food,” Day Book, Chicago, IL, April 15, 1912, pg 25-28.

Kiter, Tammy. "Life on the Veg: Early Vegetarianism in America." From the Stacks, New-York Historical Society, June 22, 2017. https://blog.nyhistory.org/life-on-the-veg-early-vegetarianism-in-america/

Landry, Alysa. "Was the Pre-Colonial Choctaw Native American Diet Vegetarian?" Indian Country Today, September 13, 2018. https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/pre-colonial-choctaw-native-american-diet-vegetarian

Mercer, Amirah. "A Homecoming," Eater.com, January 14, 2021. https://www.eater.com/22229322/black-veganism-history-black-panthers-dick-gregory-nation-of-islam-alvenia-fulton

Miller, Laura J. Building Nature’s Market: The Business and Politics of Natural Foods. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Muhammad, A.J. "Alvenia Fulton: A Pioneer in the Health and Wellness Industry." New York Public Library Blog, May 18, 2018. https://www.nypl.org/blog/2018/05/18/alvenia-fulton-pioneer-health-wellness-industry

Murphy, Maureen O'Rourke. Compassionate Stranger: Asenath Nicholson and the Great Irish Famine. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2016.

Potter, Dave. “Gregory Starts Eating Again After 54 Days." Chicago Defender, Jan. 10, 1968.

Opie, Frederick Douglass. "Dr. Fulton's Influence." FredOpie.com, July 27, 2021. http://www.fredopie.com/food/2021/7/27/dr-fultons-influence

Reber, Patricia Bixler. "Asenath Nicholson - from Graham crackers to the Irish famine." Researching Food History, September 11, 2017. http://researchingfoodhistory.blogspot.com/2017/09/asenath-nicholson-from-graham-crackers.html

Struzzi, Diane. "Natural Healer Alvenia Fulton." Chicago Tribune, March 20, 1999. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1999-03-20-9903200076-story.html

Article by Ella Wagner, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

Tags

- women's history

- suffrage

- social reform

- temperance movement

- women and the environment

- engaging with the environment

- african american history

- african american women

- food history

- vegetarianism

- new york

- illinois

- chicago

- vermont

- massachusetts

- transcendentalism

- agricultural history

- farming

- places of article

- places of...