Last updated: January 15, 2025

Article

The Complicated Legacy of Peter Faneuil

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

In March 1743, Boston's newly constructed town meeting hall and marketplace hosted the funeral of the building’s benefactor, Peter Faneuil. A Boston News-Letter correspondent described Faneuil as, "a gentleman possessed of a very ample fortune, and a most generous spirit…whose hospitality to all, and a secret unbounded charity to the poor, made…his death a general loss… to the inhabitants."[1]

At the time of his death, Peter Faneuil's "very ample fortune" made him one of the wealthiest people in Boston. Similar to the majority of Boston’s colonial elite, Faneuil made his money through trade in the Atlantic world. This network of Transatlantic Trade proved extremely lucrative in part because of the institution of slavery. Merchants such as Faneuil built their financial empires by trafficking enslaved individuals and trading goods consumed and produced by enslaved labor. Though Faneuil cannot be characterized as a major slave trader, his complicity in this system offers a window into the Transatlantic economy of 1700s Boston.

Born in New York in 1700, Peter Faneuil became one of the first in his family to grow up in America. His French Huguenot family fled their native France following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. Following his father’s death in 1719, Faneuil and his younger brother Benjamin moved to Boston to apprentice with their uncle, Andrew Faneuil.[2] By the time of their arrival, Andrew Faneuil had established himself as a successful merchant, amassing his fortune through a vast network of trade.

New England's colonial economy relied upon these Atlantic world trade networks. Its poor climate and rocky soil ruled out the possibility of profitable cash crops. However, Boston's deep natural harbor, proximity to rich fishing grounds, and access to shipbuilding supplies gave rise to a thriving shipping industry. Through his uncle, Peter Faneuil learned to navigate this commercial enterprise, eventually managing the operation when Andrew became ill. In 1738, Andrew Faneuil died and left his entire fortune to Peter.

As the heir to his uncle's vast fortune, Peter Faneuil focused on growing his family’s financial empire. He expanded an extensive network of trade through contacts in the West Indies, Canso, London, Louisbourg, France, Spain, and Africa. Within this network, Faneuil traded a wide variety of goods including, but not limited to, fish, rum, molasses, sugar, manufactured goods, and timber. Determined to amass as much wealth as possible, Faneuil traded anything that could net him a profit.

Faneuil's drive for financial success came at a significant human cost. During the late 1730s, when Peter Faneuil inherited his uncle's fortune, the institution of slavery permeated every aspect of the Transatlantic economy. Many New England merchants imported vast quantities of molasses, sugar, and rum, all produced by enslaved labor. In Peter Faneuil's invoice book, entries such as "3 Hogsheads [approximately 189 gallons] of rum" and "77 tierces molasses, 9 hogshead molasses [totaling approximately 3,800 gallons], 8 tierces sugar [approximately 336 gallons]" offer a window into the quantities of goods purchased from plantations.[3] Faneuil’s willingness to profit from the trade of goods produced by enslaved labor demonstrated his acceptance of and complicity with the institution of slavery.

New England merchants also fueled the institution of slavery in other ways. By the early 1700s, codfish had become one of the region's most important exports. Merchants sent quality cod to Southern Europe, meeting a high demand from the largely Catholic population. Unable to market their lower grade fish in Europe, New England merchants turned to the West Indies. There, enslavers readily purchased the cheap, low quality fish, often referred to as "refuse grade," to feed the enslaved people on their plantations.

Courtesey of Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School

As one historian argues, "New England commodities provided the energy that was consumed and then burned calorie by calorie in slave labor, converted ultimately into a commodity perfect for the world market."[4] Faneuil’s financial records concur. A July 15, 1737, entry stated, "fish (15,000 quintals [over 1.6 million pounds]); some to ship to Portugal; refuse grade to West Indies for molasses and rum, now in short supply in Boston; especially rum from Cape Francois."[5] This entry illustrates Faneuil’s decision to send a large quantity of fish to Spain, while sending refuse grade fish to the West Indies. The profit from the refuse grade fish then allowed Faneuil's contact to purchase molasses and rum for the Boston market. Both the molasses and rum were produced by enslaved labor, fed with refuse grade fish that originated in Boston.

While slavery thrived in the Southern Colonies and the West Indies, it existed on a smaller scale in the New England region. In 1740s Boston, enslaved individuals made up roughly ten percent of the town’s population.[6] Though Faneuil's main source of income did not directly involve the Transatlantic Slave Trade, he participated in the trade and owned enslaved people.

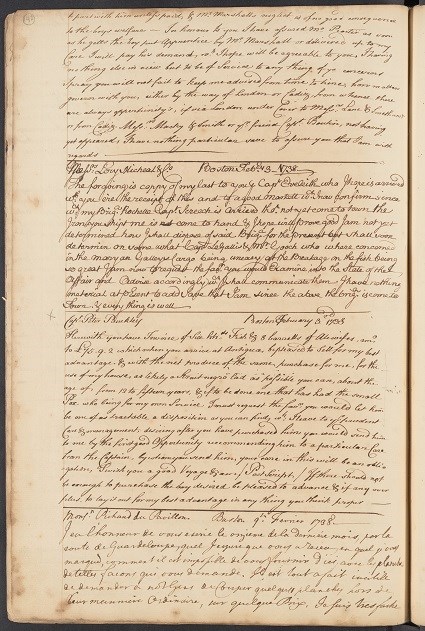

The most damning example of Faneuil's direct involvement with the Transatlantic Slave Trade comes from the voyage of the Jolly Batchelor. Initially sent to Guinea from Boston, the ship returned to Rhode Island after Faneuil’s 1742 death, with "20 Negroes" amongst its cargo.[7] While records do not indicate who made the decision to purchase those "20 Negroes," on at least one occasion, Faneuil directed one of his captains to purchase an enslaved person. In a 1738 letter to his ship captain Peter Buckley, Faneuil requested that, "With the net proceeds of the same purchase for me, for the use of my house, as likely a strait negro lad as possibly you can, about the age from twelve to fifteen years."[8]

At the time of his death, Faneuil's will recorded his ownership of five enslaved individuals.[9] Although the sources that directly tie Faneuil to owning enslaved individuals and the slave trade are limited, they speak to a merchant willing to ignore human costs in order to make a profit.

In the years following Faneuil's death, Bostonians crafted a simple legacy of a complicated man. During the Revolutionary War Era, Faneuil Hall forged a new identity for itself as the "Cradle of Liberty." As revolutionaries, abolitionists, suffragists, and modern-day activists adopted Faneuil Hall as the site of their speeches, protests, and celebrations, the memory of a generous man slowly replaced the reality of a successful merchant with strong connections to slavery.

Learn more by exploring this story map on The Atlantic Empire of Peter Faneuil.

Invoices and Day Books

Piecing together Faneuil's EmpireSugar, Salt Cod, & Enslaved Africans

The Atlantic Empire of Peter FaneuilFootnotes

[1] According to town meeting records, Bostonians voted to name the building after Faneuil on September 13, 1742, six months before his death. See "A report of the record commissioners of the city of Boston containing the Boston records from 1729 to 1742," Boston Record Commissioners (Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, 1885), 306-307. For quote, see Abraham English Brown, Faneuil Hall and Faneuil Hall Market or, Peter Faneuil and His Gift (Boston, Lee and Shepard, Wellesley College Library), 103 archive.org.

[2] Jonathan M. Beagle "Remembering Peter Faneuil: Yankees, Huguenots, and Ethnicity in Boston, 1743-1900," The New England Quarterly 75, no. 3 (2002), 390.

[3] For Peter Faneuil’s invoice book see: Invoice book, 1725-1729. Peter Faneuil Papers, 1716-1739. Volume F-3, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School. (link here)

[4] Wendy Warren, New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America, 58.

[5] Hancock family, Hancock family papers, 1664-1854 (inclusive), Peter Faneuil papers, 1716-1739. Letterbook (business), 1737-1739. Volume F-4, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School. Seq. 14 (link here).

[6] Robert E. Desrochers Jr, “Slave-for-Sale Advertisements and Slavery in Massachusetts, 1704-1781,”

The William and Mary Quarterly 55, no. 3 (2002), 644.

[7] Slave Voyages Database, Voyages: The Transatlantic Slave-Trade Database, Voyage ID 25185, https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database.

[8] Robert E. Desrochers Jr, “Slave-for-Sale Advertisements and Slavery in Massachusetts, 1704-1781”

The William and Mary Quarterly, 649.

[9] Abraham English Brown, Faneuil Hall and Faneuil Hall Market or, Peter Faneuil and His Gift (Boston, Lee and Shepard. Wellesley College Library), 111.