Last updated: September 11, 2024

Article

African Descended Soldiers at Fort Schuyler & in the Mohawk Valley

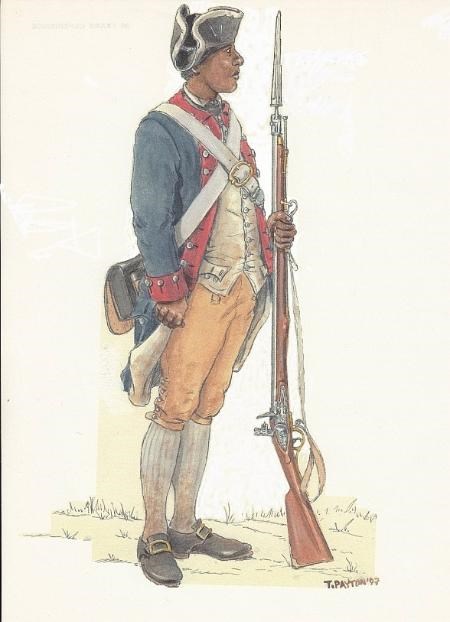

National Park Service/T. Payton, 1997

While it is difficult to say for certain that many soldiers of color or African descent served at American Fort Schuyler (Stanwix), people of color played an integral, if not overlooked roll in early American history. The American Revolution was no different. A few names, like Cato Harris and Garret Van Schaick have been linked to the history of the fort. Others, though likely, remain mysteries.

Not Just Numbers

There were people of color throughout the Colony, later the State, of New York. Slavery began in New York during the Dutch era, and by the time of the Revolution, New York had the highest population of enslaved persons of all the Northern States. At the start of the Revolution, approximately 500,000 African descended people lived in the colonies (out of a total population around 2.1 million), of whom some 450,000 (90%) were enslaved. Prominent upstate New York families, like the Schuylers, Herkimers, Van Schaicks, and Johnsons, all counted enslaved persons as their “property.” Free blacks comprised only 2.4% of the overall population and about 10% of the African descended population. Indeed, there were more enslaved people in New York at the end of the Revolution than at the beginning, and the institution of slavery was not abolished in the state until 1827!

We Don’t Know What We Don’t Know

There are comparatively few official records of enslaved or free persons of color throughout the state at that time, and even fewer of those who decided to join the Continental Army or various New York militias. A tragedy for remembering these peoples came in the late 1800s and early 1900s when an untold number of New York State Revolutionary War archives (including muster, descriptive, and pension rolls) were lost in fires in Albany, NY. However, a few records did survive and were compiled in the 1970s.

Others survived because they were in different states entirely. For example, it is known that in January of 1783, the 1st Rhode Island Regiment (famously known as the “Black Regiment"), were placed under command of Colonel Marinus Willett and his levy troops in order to take Fort Ontario in western New York from the British. They comprised a portion of a larger group of nearly 500 that would have passed the area of Fort Schuyler on their way through the frontier. At least one was left behind due to incapacitation and many others suffered frostbite in the cold weather of the Great Lakes region. However, exact names of the participants are difficult to track down.

A Less Perfect Union?

African descended soldiers served in military units throughout the 13 States and most of them were integrated right into the main army. The US military didn’t segregate its forces based on color until the War of 1812. They remained segregated until 1947. The wives of these Continenal Soldiers would have assisted in the camps and their children would have played with the others, regardless of race. People of color fought in provincial regiments prior to the war, and at least 5,000 African descended soldiers and sailors, free and slave, served the Revolutionary "cause."

It is impossible to say why or under what circumstances these folks joined the “cause.” Some may have joined for similar reasons to their European descended counterparts. Others were certainly enslaved and compelled to join on behalf of their enslavers. Still more surely joined to escape enslavement. On March 20, 1781, New York State passed a law allowing enslavers to deliver men to serve on the frontier in exchange for 500 acres of bounty land; in exchange for three years worth of service (or until a regular discharge), the enslaved man was to be granted their freedom. Many of these men ended up under command of Marinus Willett.

It is impossible to know all of their ages and nearly impossible to discover what happened to them after the war...if they even survived it. During the war, those who were enslaved, often had their earned pay confiscated by their enslavers. After the war, the majority never saw any kind of pension and some were even returned to enslavement. Some were denied because they served while enslaved; and even decades later when many of their European descended counterparts (and their widows) had collected them, they were still denied recognition.

Remember Them

The following are the names of other men who were verified to have served in military units associated with Fort Schuyler and therefore, the most likely to have served at the fort or in the Mohawk Valley at some point during the war. Many names are what more modern people would consider “stereotypical.” Examples seen regularly include “Negro,” "Black," and “Caesar.” But these men (and their forgotten families), stepped out of the fringes to serve a nation that kept them and their descendants in the shadows for nearly another two centuries.

Image Credit: Yale University Art Gallery

Atayataghlonghta – Colonel Louis Joseph Cook

Colonel Louis was born in the area of Saratoga, NY in about 1740, to an Abenaki mother and a Africa father. He was adopted into a Mohawk tribe in Canada. He spent nearly his entire life fighting against British rule. First as part of the French forces that took Fort Oswego in the 1750s. Then as the highest ranking Native and African officer in the American Continental Army. He led raids and battle actions across New York and fought at the Battle of Oriskany. In 1784, he negotiated on behalf of the Oneidas during the sessions held at the remains of Fort Stanwix/Schuyler. In his 70s, he joined the Americans to fight against the British yet again, during the War of 1812, and in October of 1814 died from injuries he sustained in battle.

Cask Africa, Private, 1st NY Regiment

Africa was enlisted from June through December 1776.

Pomp Williams, Private, 1st NY Regiment

Garret Van Schaick (enslaved), 1st NY Regiment

Born in approximately 1764. Garret was enslaved by Colonel Goose Van Schaick and accompanied him to Fort Schuyler (Stanwix) as a servant on several occasions. Garret died at age 65 in Monroe County, NY on May 16, 1829.

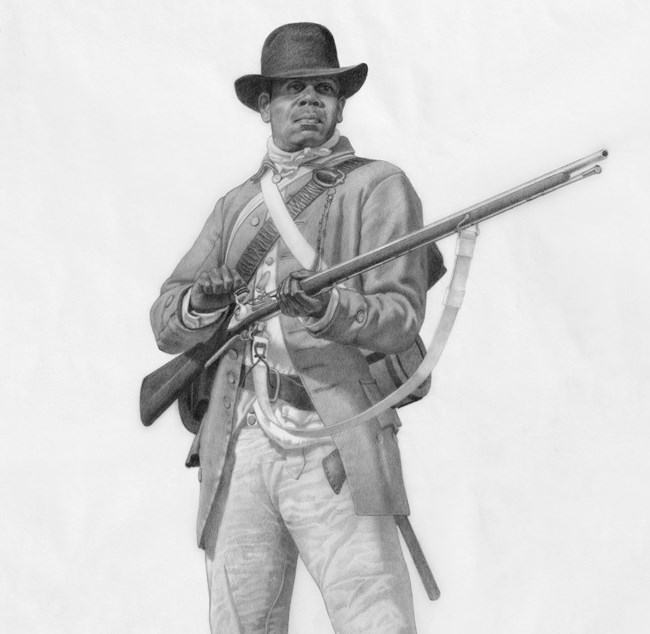

National Park Service

James Weeks/Green, Private, 2nd NY Regiment

Born circa 1757, Weeks was a known free man of color that stood 5'8" with "light" colored eyes and hair. He first enlisted in April of 1778, at age 19, for nine months of service, much of which he spent on the sick rosters. Weeks was discharged at Fort Schuyler (Stanwix) in December of 1780. At the time he served as a "waggoneer," in charge of hauling supplies for the army. He reenlisted in April of 1782 into Captain Israel Smith’s company. Most of that time was spent guarding the Hudson Valley against potential British attack from the New York City area. He was discharged in July of 1783 at Camp Snakehill near New Windsor, NY.

After the war, he married and had children. He applied for a pension in 1818, 1824, and again in 1825 while living in New Jersey. His first two requests were denied; the first for "inefficient forms and requirements," and the second on account of Weeks being unable to pay for the paperwork involved. By that point, his eyesight was poor and he still worked as a laborer to support himself. His family lived in New York City. It seems as if he bounced back and forth between the two areas for several years. He was finally awarded a pension at age 68 in May of 1825 of about $8 a month. It is unknown when he passed or where he was buried.

Caesar Haight, Private, 2nd NY Regiment

Peter Green (Enslaved), Private, 2nd NY Regiment

Green was born in around 1751 in Africa. Green was kidnapped at a young age and enslaved shortly after the end of the French & Indian (Seven Years) War. It is unknown if "Peter Green" was his name by birth or by enslavement. He was enlisted into the Continental Army in 1782. He served with the 2nd NY Regiment in Captain Samuel Pell’s Company until 1783. It is believed that he was given his freedom as a result of his service. After the war, he moved to Colrain, MA and was awarded a military pension. He married Violette (also born in Africa and enlsaved) and had two sons: Peter Jr. (a blacksmith) and Charles (who took in a young girl as his daughter when her employers attempted to sell her into enslavement). He was still recorded living there at age 84 in 1835. He passed in 1836 at the approximate age of 86.

Cato Harris, Private, 2nd NY Regiment

It is unknown when or where Cato Harris was born, but muster records indicate that he possibly came from the Baltimore, MD area. Harris was “appointed” for the duration of the war to Captain Israel Smith’s Company of the 2nd NY on February 18, 1781. He was stationed at Fort Schuyler (Stanwix) until June of 1781, when the fort burnt down. Then at Fort Herkimer with his company until July of 1781. Over the course of the summer, the 2nd NY made their way to Virginia to join the larger Continental Army. Harris fought with his regiment that fall at the Battle of Yorktown and witnessed the British surrender on October 19, 1781. While the regiment was returning to New York, Harris died on November 27, 1781. It is possible he died while they were crossing the Delaware River. It was noted the wind and river were both rough and there was “stormy weather” for several days before and after his death.

Pomp Lamb, Private, 2nd NY Regiment

Lamb enlisted in the Continental Army on July 25, 1780 for a 3 month term. He was discharged in Schenectady, NY.

Cesar Dunmore, Private, 4th NY Regiment

Cesar Dunmore was enlisted for a 9 month term in January of 1778, but ended up serving nearly a year. His regiment guarded the Hudson Valley near Peeskill, NY and marched north ending up at Fort Plank in the Mohawk Valley. He was discharged on February 8, 1779. It is unknown what happened to him after his enlistment expired.

Caesar Flood, Private, 4th NY Regiment

Cato Moulton, Drummer, 4th NY Regiment

Moulton was born circa 1756. He was described as being 5'8" tall with black hair and skin. He enlisted in the Continental Army on January 1, 1777 as a drummer for the duration of the war. He spent his first winter with his regiment at Valley Forge. He spent three months sick in his quarters there. The following year he was stationed at White Plains, NY, Peekskill, NY, Fort Plain in the Mohawk Valley, and became ill at Camp Pompton. In the summer of 1779, the Regiment participated in the violent Sullivan Clinton Campaign against the Haudenosaunee Nations. The regiment then spent the winter encamped at Morristown, NJ. In January 1780, Moulton was placed on furlough by Colonel Weisenfelss. He was supposed to report back to service in April and instead deserted. It is unknown what happened to him.

Primus Wiley, Private, 4th NY Regiment

Benjamin Lattimore, Private 5th NY Regiment

Benjamin Lattimore was born a free man in 1761, in Weathersfield, Connecticut. At the outbreak of the Revolutionary War he was living in Ulster County, near New Marlborough, several miles south of Poughkeepsie. Lattimore enlisted with the 5th NY Regiment, Continental Army in 1776. A few days later his company was sent to New York City, where they took part in the Battle of Manhattan. Later that year he was on duty at Fort Montgomery, on the Hudson, when he was captured along with hundreds of other Continentals by the British; after which he was forced to act as a house slave in a British officer's home in New York City. Lattimore was re-captured by the Americans in Westchester, and re-joined the Continental Army. Marching overland to Schoharie to spend the winter in 1778, the next winter, Lattimore’s regiment participated in the Battle of New Town in the 1779 Sullivan Expedition along the western frontiers, designed to punish the Haudenosaunee for raiding European settlements.

By the late 1790s Lattimore and his family moved to Albany. He was licensed by the city as a “cartman” (authorized to haul cargo through the city streets). In 1804, he married Dina, who was the servant maid a local doctor. They had at least three children; Benjamin Jr., William, and Mary Lattimore Jackson. By about 1810, Lattimore also owned a grocery store and began to accumulate real estate. Throughout the rest of his life Lattimore was active in advancing the conditions of African-Americans in Albany (also known as the "Afro-Albanian" Community).

Despite being born a free man, Benjamin in 1820 was summonsed to court to defend himself against allegations that he was an escaped slave. The testimony given by himself and many of members of the Albany community provides incredible details on his life. In 1834, he applied for his Revolutionary War pension and received an annual allowance of $80 and back pay of $240. He was part of a group that established the first “Albany School for Educating People of Color” in the early 1800s, was founding member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and was chairman of the Albany Committee to Celebrate the Abolition of Slavery in New York State in 1827. He died in 1838 at the age of 78 and was buried in the AME Cemetery. Records indicate that his remains were moved to Albany Rural Cemetery, but his headstone has since gone missing.

American soldiers at the siege of Yorktown, by Jean-Baptiste-Antoine DeVerger, watercolor, 1781

Elisha Baker, Private, Rhode Island Regiment

Prince Bent (enslaved), Private, Rhode Island Regiment

Bent was born in Africa along the Guinea Coast. He did not know how old he was, but enlistment records indicate he was estimated to be 20 when he was enlisted into Colonel Green's Regiment in 1778. He stood at 5'4" tall and worked as a laborer in Westerly, Rhode Island before his service He served at Saratoga, in the Sullivan-Clinton Campaign, at the Battle of Yorktown, and in the Oswego Expedition. At some point he was captured and spent eight months as an enemy prisoner before escaping. He applied for a pension in April of 1818. It is unknown if his application was granted.

William Frank (free), Private, Rhode Island Regiment

Cato Green (enslaved), Private, Rhode Island Regiment

Cato Green was born circa 1760, somewhere in the modern nation of Guinea in Africa. In his youth, he was captured and sold as a slave in the British Colony of Rhode Island. When the American Revolution broke out, Cato enlisted in the Continental Army in July of 1778 to "obtain his freedom." Under Colonel Green and Colonel Olney, his regiment served in various locations across the northeast. He also worked as a "servant" for Col. Olney. In fall of 1781, he participated in the Battle of Yorktown with the rest of the Rhode Island Regiment. The following winter, his company was sent to the Mohawk Valley to raid and capture British Fort Oswego, along the eastern end of Lake Ontario. During the disastrous January 1782 campaign, freezing weather conditions led to at least 10 members of his company dying within a one-week period. Countless others were maimed for life by frostbite and other injuries. Cato did not record any personal injuries in the campaign. He was honorably discharged on June 15, 1783.

After the war, Cato settled in Cranston, RI outside of Providence and worked as a laborer. He had at least two wives over the course of his life. One, Jane Tyler, he married on October 30, 1803. Sadly, Cato outlived both of them. On April 2, 1818 he initially applied for and was granted a pension under the new "act to provide certain persons engaged in the land and naval service of the of the United States, in the revolutionary war." However, only two years later, it appeared his pension was in danger. On June 20, 1820, Cato applied a second time for a pension stating that at age 80 he was too old to work, and if denied he'd have to rely on charity to survive. At the time of his application, he had no family to speak of and lived in an old house on one acre of land in Cranston, RI with only a bed, a few pieces of silverware, a table, and four chairs to furnish it. It is unknown if this second pension request was approved or when he died.

Reuben Roberts, Private, Rhode Island Regiment

Ruben Roberts was born circa 1762. He enlisted in the Rhode Island "Black" Regiment in 1777 and served for the duration of the war. In 1781, he and his comrades served at the Battle of Yorktown. Although it was known as the "final battle" of the war, it was by far the final military action of the war. In 1782, nearly 500 Rhode Island Continentals found themselves transferred to the command of Colonel Marinus Willett. Under his leadership, they marched up through the Mohawk Valley, through the remains of Fort Schuyler, past the border to Oneida Lake, and finally heading north on the Oswego River to capture the fort occupied by the British on the north bank of the river's mouth on Lake Ontario. After this long trek, in the dead of winter January 1783, the soldiers had been led astray by their native scouts. At one point, fearing their capture because of the noise, all the dogs following the regiment were killed. Later, the frozen animals were eaten due to lack of food. The men had built ladders to scale the walls of the British fort, but instead of attacking, at least two surrendered hoping to find warmer conditions with the enemy. In these freezing cold nights Roberts suffered frostbite so intense he lost the use of his feet and became "lame." They took cover in the remains of Fort Schuyler on their retreat. Shortly after his return to the Hudson Valley he broke a leg. He was discharged shortly afterwards.

After the war, Roberts married and had several children in the area of Warwick, RI, where he worked as a laborer. In 1818, Roberts applied for a pension. He was indigent, owing over $40 to various debtors and owning less than $10 in property and he was suffering too much from his war injuries to work. Several friends and fellow soldiers testified on his behalf. He was granted his pension request at the rate of $80 per year; a life changing amount. He passed on September 5, 1838 near the age of 76.

Prince Vaughan, Private, Rhode Island Regiment

Prince Vaughan was born circa 1763 in Rhode Island. He stood 5'4.5" tall and worked as a laborer. Vaughan enlisted in the Rhode Island "Black" Regiment in 1777, at the age of 19, for the duration of the war. He fought at the Battle of White Plains, at Yorktown, and participated in the Oswego expedition in winter 1782/83. During the ill-fated campaign, his right foot and toes were completely frozen as well as several toes on his left side. He was left with a disability for the rest of his life. He was granted a pension in 1785 on account of his injuries. To help support himself he worked as a shoe shiner and ran an oyster stand in New York City. In 1818, after four years of suffering from illness and rheumatism, the entirety of his earthly goods totaled $1.82. That same year he applied for another pension, which was awarded at the rate of $8 per month. According to his pension testimony, he had no family. He passed on November 23, 1820.

National Park Service

Henry Bakeman, Private, Willett's Levies

Henry Bakeman had enlisted at about age 16 in April 1781, after British and Mohawk troops had destroyed his home village of Stone Arabia in October 1780. Involved first in carrying packages from one Patriot fort to another, resulting in “many skirmishes with the Indiana & Tories,” Bakeman found himself involved in what would be the last engagement of the Revolutionary War: the planned attack on British Fort Oswego. Disaster awaited them. Crossing the frozen Oneida Lake on sleighs on February 9, they stopped at Oswego Falls (now Fulton) to build ladders to scale the walls of Fort Ontario. A wrong turn through heavy snow and swampland brought them to the Fort far past sunrise on the morning of February 11, too late to surprise its defenders. Turning homeward, they left three people to die in the snow.

Bakeman survived, but his frozen feet left him crippled for the rest of his life. Bakeman left the army in 1783, married a woman of Dutch descent, and returned to Oswego Falls, where he operated a ferry across the Oswego River, bought a farm, received a certificate of freedom in 1819 from the Town of Granby, and died on February 6, 1835.

Bakeman’s story was well-documented through his pension record in 1834. But his experience reflected that of many other Black Revolutionary War soldiers. To honor his service, the Daughters of the American Revolution erected a memorial stone in Mt. Adnah Cemetery, Fulton. Bakeman’s march took him along the Mohawk Valley, past Fort Stanwix, to the Oneida Carry into Wood Creek and Oneida Lake.

-

Brave Boy (enslaved?), Private, Weisenfelss’ Levies

-

Jack, Private, Willett’s Levies

Jack was eventually awarded pension land.

-

Robin (enslaved), Private, Weisenfelss’ Levies

-

Prince (enslaved), Private, Willett’s Levies

-

Ransom Brazillia/Barsillay (enslaved), Private, Weisenfelss’ Levies

Ransom's pay was collected by his presumable enslaver, Jacob Tremper.

-

Cesar Bassett (enslaved?), Private, Weisenfelss’ Levies

-

Negro Boston (enslaved?), Private, Willett’s Levies

Boston was enlisted in Willett's Levies at Fort Herkimer on July 24, 1781. He served a five month term.

-

Tunis Brown (enslaved), Private, Willett’s Levies

-

Prince Cato (enslaved), Private, Willett’s and Weisenfelss’ Levies

Cato was enlisted on August 11, 1782 on behalf of his enslaver, John DeWitt.

-

Negro Prince (enslaved), Private, Willett’s Levies

-

Jube Robins (enslaved), Private, Willett’s Levies

Robins was enlisted on behalf of his enslaver, William B. Whiting, who was paid at least £9.50 for Robins' service.

-

Prime Thompson (enslaved?), Private, Willett’s Levies

Thompson was enlisted on behalf of a man named "Rogens."

-

Black Walter (enslaved), Private, Weisenfelss’ Levies

Walter was eventually awarded pension land.

-

Prince Hubbard, Private, Weisenfelss’ Levies

-

Black Minck (enslaved), Private, Weisenfelss’ Levies

Minck was enlisted on behalf of his enslaver, Peter Prelso.

-

Prince Sackett (enslaved), Private, Weisenfelss’ Levies

Prince was enlisted on behalf of his enslaver, Richard Sackett.

-

Jack Thompson/Swartwout (enslaved), Private, Weisenfelss’ and Willett's Levies

Thompson was enlisted on behalf of his enslaver, John Ball.

-

Tunes Terwilliger (enslaved), Private Weisenfelss' Levies

Justus Banks and Aldert Rosa were deputized to collect his pay on behalf of Tunes' unknown enslaver.

-

Solomon White (enslaved?), Private Weisenfelss' Levies

-

War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, Record Group 93. U.S. National Archives.

-

The Orderly Books of the 2nd and 4th NY Regiment

-

The Journal of Samuel Tallmadge

-

Forgotten Patriots: African American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War. Grundset, Eric G. et al. National Society of the Daughters of the Revolution, 2008.

-

"Early African Americans in Colrain," Colrain Historical Society. Accessed December 6, 2022.

- The Biography of Benjamin Lattimore, New York State Museum. Accessed September 29, 2023.

- The Negro in the American Revolution. Quarles, Benjamin. Unversity of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, Reprint 1996.

- Historical Notes on the Employment of Negroes in the American Army of the Revolution. Moore, George H. New York, 1862.

- RPW, James Weeks/Green, S.33269. US National Archives.

- RPW, Benjamin Latimore. US National Archives.

- RPW, Cato Green, S-38753. US National Archives.

RPW, Prince Vaughan, S.42603. US National Archives.

- RPW, Ruben Roberts, S.39,834. US National Archives.

- RPW, Prince Bent, S.38,541. US National Archives.

- “We Took to Ourselves Liberty”: Historic Sites Relating to the Underground Railroad, Abolitionism, and African American Life in Oneida County and Beyond. Judith Wellman, Principal Investigator, with Jan DeAmicis, Mary Hayes Gordon, Jessica Harney, Deirdre Sinnott, and Milton Sernett.Prepared under a cooperative agreement between The Organization of American Historians and the National Park Service January 2022.

Tags

- fort stanwix national monument

- fostppl

- african american history

- american revolution

- us army

- military history

- continental army

- american revolution 250

- people of color

- untold stories

- patriots of color

- african american heritage

- african american military

- black history

- african american soldiers

- military

- african american

- african american soldier

- morristown national historical park

- war

- african americans

- american revolutionary war

- revolutionary war