Last updated: July 28, 2025

Person

Henry Bakeman

National Park Service / Ranger Dan U.

On the cold morning of February 9, 1783, seventeen-year-old Henry Bakeman marched past Fort Stanwix with four to five hundred fellow soldiers. Like Henry Bakeman, as many as one hundred of these soldiers were men of color. Some were free; some were enslaved. Some came from Mohawk Valley farms; others were part of the integrated First Rhode Island Regiment. Their goal? A surprise attack on British-held Fort Oswego.

Bakeman had enlisted in April 1781, after British and Mohawk troops had destroyed his home village of Stone Arabia in October 1780. Involved first in carrying packages from one Patriot fort to another, resulting in “many skirmishes with the Indiana & Tories,” Bakeman found himself now involved in what would be the last engagement of the Revolutionary War. Disaster awaited them.

Crossing the frozen Oneida Lake on sleighs on February 9, they stopped at Oswego Falls (now Fulton) to build ladders to scale the walls of Fort Ontario. A wrong turn through heavy snow and swampland brought them to the Fort far past sunrise on the morning of February 11, too late to surprise its defenders. Turning homeward, they left three people to die in the snow. Bakeman survived, but his frozen feet left him crippled for the rest of his life. Bakeman left the army in 1783, married a woman of Dutch descent, and returned to Oswego Falls, where he operated a ferry across the Oswego River, bought a farm, received a certificate of freedom in 1819 from the Town of Granby, and died on February 6, 1835.

Bakeman’s story was well-documented through his pension record in 1834. But his experience reflected that of many other Black Revolutionary War soldiers. To honor his service, the Daughters of the American Revolution erected a memorial stone in Mt. Adnah Cemetery, Fulton. Bakeman’s march took him along the Mohawk Valley, past Fort Stanwix, to the Oneida Carry into Wood Creek and Oneida Lake. It was the most important route west from the Hudson Valley to the whole Great Lakes region. Oneida County’s importance depended on this geographic location.

Bakeman and other African Americans who enlisted in New York State were certainly aware of a law passed by the legislature in March 1781. It freed all enslaved people who served in the American Army for three years or until their regular discharge, and it gave five hundred acres of land to those who gave permission for enslaved people to enlist.1

British soldiers, Mohawks, and Loyalists under the command of Sir John Johnson destroyed Stone Arabia and the surrounding farms in October 1780. That raid almost certainly included the home of Henry Bakeman, a fifteen-year-old African American boy. Born on January 1, 1765, in Rocky Hill (in New Jersey or New York State), he moved with his father when he was three years old to Simon’s Kill near Schenectady, then in 1770 to a place near Fort Plain, and then in 1776 to the German settlement of Stone Arabia (or “Stone Rabby,” as Bakeman called it in his pension application), all in the Mohawk Valley. We do not know whether Bakeman was free or enslaved.2

Desperately trying to defend American frontiers, Congress also increasingly faced unrest among its troops. Lack of funds and depreciation of currency led many soldiers and officers alike to complain of lack of pay. Marinus Willett was one of three officers who presented a petition to the New York State legislature, asking for proper payment. At the same time, Congress consolidated its forces to bring each regiment up to full strength. On January 1, 1781, for example, Congress cut New York regiments in the Continental Army from five to two. In the process, some lesser-ranking officers lost their positions. Marinus Willett, by then a full colonel in charge of the Fifth New York Regiment, was suddenly out of a job. In these dire circumstances, Governor Clinton convinced Willett to accept command in April 1781 of all state and militia troops in the Mohawk Valley. Supposedly made up of 1,100 men, the large Tryon County militia was severely depleted when Willett took command. “I don’t think I shall give a very wild account if I say, that one third have been killed, or carried captive by the enemy; one third removed to the interior places of the country; and one third deserted to the enemy.”

Colonel Willett desperately needed to recruit men for his militia. Perhaps in response to this need for manpower, the New York State legislature decided in 1781 to free all enslaved men who served as soldiers for at least three years. Among those African Americans who joined Willett’s forces was young Henry Bakeman. Did British and Indian destruction of Stone Arabia and surrounding farms in October 1780 inspire Bakeman to join the Patriot Army?

Was Bakeman enslaved and viewed the army as a way to gain his freedom? Certainly, he must have been aware of New York State’s decision to give freedom to enslaved people who joined the army. Whatever his motivations, Bakeman enlisted a month later in Captain Henry French’s company (other sources suggest that he enlisted under Captain Benjamin Pierce or Putnam) at Stone Arabia on April 17, 1781. Bakeman’s first enlistment was for nine months. In July 1781, he re-enlisted for three years in a company of light infantry led by Captain Peter P. Tiree (or perhaps Captain Cannon Jr.). Both companies served in Colonel Marinus Willett’s regiment.

Bakeman’s fate was tied to that of his commander Colonel Marinus Willett. And he had joined Willett’s regiment just in time to take part in the very last campaign of the American Revolution. Washington hoped to ensure American control of western lands after the Revolution by capturing British-held Fort Oswego, where the Oswego River reached Lake Ontario. The British had reoccupied this fort in 1782. Washington wanted it back. He asked Colonel Marinus Willett to lead this campaign.

In the summer of 1782, according to Bakeman’s pension application, “his duty was to carry packages between Fort Plain & Herkimer and when not engaged in this service, he did his duty in this company.” He was “not engaged in any battle of any note,” he reported, “but many skirmishes with the Indians & Tories.” His first skirmish was with Indians at Fort Plain. His role as a package carrier may have included assignments as a scout, also—a replacement for Oneida Indians whose lives had been disrupted in the 1780 raids.3

Willett’s schedule was determined by the calendar. The plan was to reach Fort Oswego in the early morning of February 11, just as the waning moon had set, so that Americans could climb fort walls under the cover of darkness, catching defenders by surprise. Washington cautioned: no surprise, then no attack. In eighteenth-century language, he had written to Willet, “If you do not succeed by Surprise, the attempt will be unwarrantable.”4

On February 8, 1783, Willett left Fort Herkimer, at German Flats, about twenty-five miles east of Fort Stanwix. He led a force of four to five hundred men, including as many as one hundred people of color. The integrated First Rhode Island regiment marched with him, as did young men of color such as Henry Bakeman from the Mohawk Valley. Joseph Perrigo, fifer for the First Rhode Island, became a lifelong friend of Henry Bakeman.5

Willett and his men, including Henry Bakeman, headed west past Fort Stanwix. After a fire left it severely damaged in 1781, the Americans abandoned Fort Stanwix. But it still stood on the main route to the Oneida Carrying Place. The regiment crossed the frozen Oneida Lake on sleighs on February 9 and then abandoned their sleighs the next day to walk through the snow to Oswego Falls (now Fulton). There they stopped to build ladders for their final assault. On February 10, they followed the river until late evening. By that time, they were only about four miles from the fort. They had four more hours until darkness would allow them to attack. Their Oneida guide, Captain John, convinced Willett to move away from the rapidly flowing river to follow snowshoe tracks that, according to Captain John, led directly to the fort. Not so. Two hours of slogging through heavy snow and swamps, carrying ladders, left the company confused and disoriented. They finally reached the fort only after dawn.6

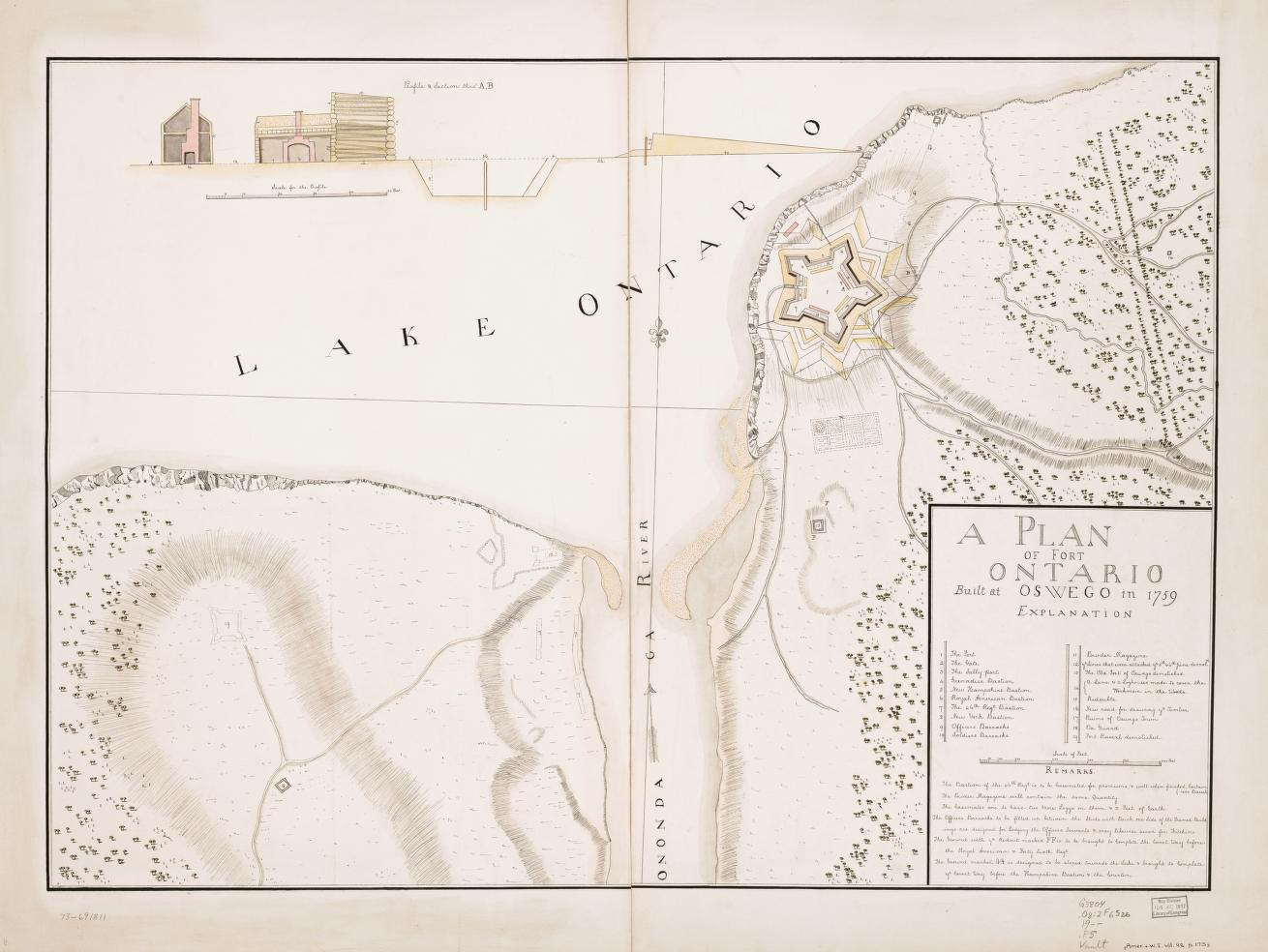

Below: A Plan of Fort Ontario built at Oswego in. [19--?, 1900] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/73691811/.

Unable to attack under cover of darkness, discouraged, cold, and disheartened, they turned around and headed back to Fort Herkimer. The return trip was a nightmare. Willett had brought no food for the trip home, expecting to stock up on supplies at Fort Oswego. Without any prospect of victory, “great fatigue got the better of the spirits of the soldiers,” Willett reported. At least three men—two from Rhode Island and one from New York—were left to die in the snow. Many suffered frostbite and permanent damage to their feet. Henry Bakeman’s feet were frozen by the end of the journey, which left him “a cripple” for the rest of his life. Bakeman noted that one soldier of color froze to death while another, “with his fiddle and song, did much to keep up the spirits of the men, and to induce them to active exercise, by which they were saved the fate of their comrade.”7

Washington recognized that the campaign against Fort Oswego had been risky at best. In the end, it was a total failure. Fort Oswego remained in British hands until the Jay Treaty of 1796.

Willett, however, was celebrated as a hero. He was best known for his exploits at Fort Stanwix in 1777. But, as historians Geake and Spears noted, “it is likely that he performed a greater, if less recognized, service in saving the Mohawk Valley.” And saving the Mohawk Valley involved people of color, as well as Oneida Indians and people of English, French, French, Scottish, and German descent.8

After his terrible ordeal in the Oswego expedition, Bakeman began a year’s service in June 1783 as a waiter or personal servant with Elias Van Bunschotten. Bakeman was discharged at Poughkeepsie in June 1784.9

Whether Bakeman was a free person of color or enslaved when he enlisted at Stone Arabia, we do not know. But he represented thousands of African Americans who joined both British and Patriot armies and navies. After the war, Bakeman returned to Montgomery County. In 1792, he married Jane Christianse, a woman of Dutch ancestry, in the Dutch Reformed Church of Fonda. Their first child, Caty, likely died. But eventually, they had at least five living children: Magdalena (Laney), Rachel, Mary, Andrew, and Benjamin.10

Some accounts suggest that Henry and Jane Bakeman lived in Charleston, Montgomery County, for eleven years. But, like thousands of other former soldiers, Henry Bakeman saw an opportunity for owning land in central and western New York, once part of Haudenosaunee territory but opened for by treaty for non-Haudenosaunee settlement. About 1800, he left Montgomery County and went west to Oswego Falls (Fulton), which he had first seen during his war service. There he bought part of Military Lot 4, on the west side of the Oswego River, and set up a ferry service. The lengthy rapids at Oswego Falls meant that most boats portaged around the Falls. Individual travelers took advantage of Bakeman’s ferry. In 1810, Bakeman was listed as a resident of the Town of Lysander, Onondaga (which then included part of Oswego County), as head of a household that included eleven free people of color.11

By 1818, Henry had accumulated enough money to purchase more land. He bought 100 acres for $500, immediately sold half of it for $276, and two months later sold another 34 acres, leaving him with 16 acres. The depression of 1819 brought financial trouble, and Henry lost his land through foreclosure in March 1820. Henry’s son Benjamin Bakeman bought this land, however, so it remained in the Bakeman family.12

In 1822–24, the only years for which we have assessment records, Bakeman paid taxes on this property. In 1822, he was taxed $1.42 for ten acres of land on Lot 4, valued at $64.00 in 1822. The assessed value rose to $120.000 in 1823. In 1824, he owned only two acres on Lot 4, valued at $10.13

Perhaps to support his claim as the legal owner of his land, Henry Bakeman approached the Granby Town Board of Supervisors in April 1819 to ask for an official certificate of freedom. We do not know why he felt that he needed to have official recognition of his free status. And we do not know whether he was born free or whether became free as a result of his service in the Revolutionary War. But two local residents of European descent certified that as long as they had known him (twenty years and fourteen years, respectively), he had been free:

Certificate of the freedom of Henry Bakeman. On this 20th day of April 1819, came before me John P. Walradt who on oath did declare and say that he has been acquainted with Henry Bakeman a mulatto person for nearly twenty years and that he always understood him to be a free person and that it was never disputed by any person. And the undersigned also being acquainted with the said Henry for upwards of fourteen years has always understood him to be a free person and a citizen of the State of New York. I therefore certify that I am fully satisfied that said Henry Bakeman aged 58 years born at Rocky hill in the State of New York born free is a free person and a lawful citizen of the State of New York.

Recorded Feb. 25, 1820 Nehemiah B. Northrup Town Clerk14

According to the 1820 census, Henry Bakeman lived in Granby as head of a household of ten free people of color, three of whom were engaged in commerce. The family began to move to separate households in the 1820s. Two Bakemans, Jacob and John, perhaps grandsons of Henry, began to operate local mills. In 1825, Jacob Bakeman bought two mills in the hamlet of West Granby, where he built a small house. John Bakeman ran a mill near what later became the Oneida Street bridge in Fulton. Henry and Jane’s son, Benjamin, moved to South Onondaga and married Rachel Day, who was born in New Jersey around 1801. They raised a large family of children, including Marinda, Oliver, Artemus, Lovicia, and Charity. By 1830, the census listed Henry Bakeman as head of a household of four people: two people of color and two white.15

In September 1834, Henry Bakeman was granted a pension for his service as a soldier. In his application, he noted that he was a cooper (perhaps working for Jacob Bakeman, making barrels for flour at the mill). He listed his assets:

Real Estate none. Personal exclusive of necessary wearing apparel and bedding as follows:

1 cow,

1 two year old heifer,

7 sheep and calf [?]

3 hogs

Tools as follows 2 janisters [?],

3 staves,

1 jack plaine,

1 hand saw,

1 old cross cut saw,

old Flat head ax,

1 narrow ax,

1 compass,

1 old post ax,

1 brest bit,

1 crzie [?],

1 old chain 4 feet long,

6 small match [?] pieces [?],

about 1 M. pine staves,

2 salt barrels,

1 4 pail [?] kettle,

4 small do,

2 small pots,

2 Tea kettles,

1 Frammel,

6 plates,

1 platter,

6 knives & forks,

1 chest,

4 Bots [beds?]

Schs?16

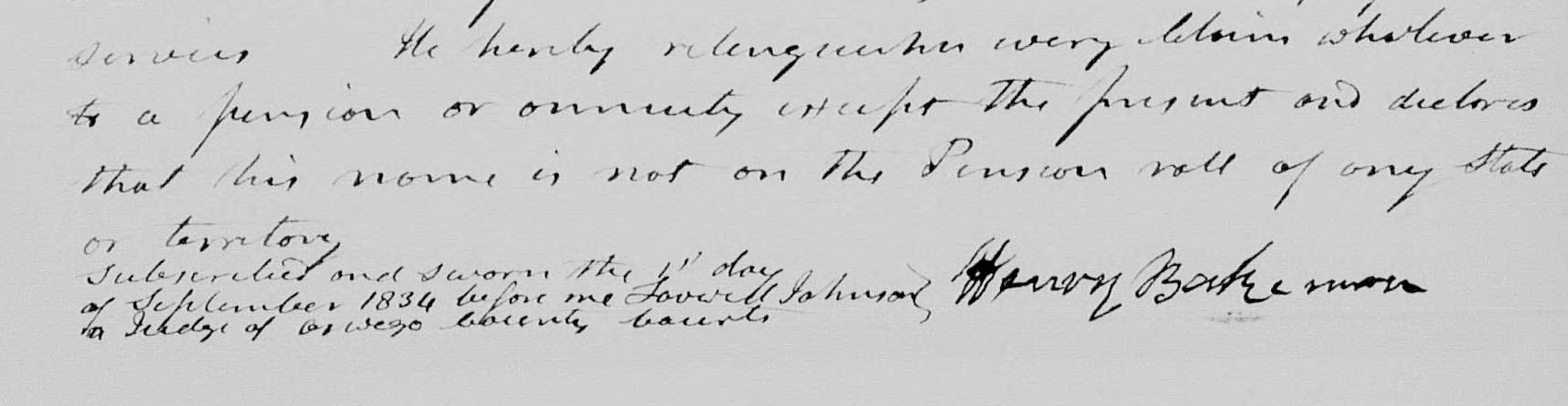

Below: An image of Bakeman's pension application with his signature.

Henry received only one pension payment before his death on February 6, 1835, at the age of seventy. Jane also received only one pension payment before her death in 1856. Both Henry and Jane are buried in South Onondaga Cemetery, near their son Benjamin’s home. A memorial stone erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution in Mt. Adnah Cemetery, Fulton, New York, memorializes Henry Bakeman as a local resident who served in the Revolution.17

One of those who accompanied Bakeman on the ill-fated expedition to Oswego was Joseph H. Perrigo. He became a friend of Henry Bakeman and moved with him to Fulton. Perrigo was a fifer for the First Rhode Island Regiment, but it is not clear whether he was of European or African descent. He moved with Bakeman to Oswego County, and he and Robert Perrigo (perhaps his brother), along with Robert’s wife Ida, are also buried in Mt. Adnah Cemetery in Fulton, New York.18

Henry Bakeman’s legacy has only recently been rediscovered. As an African American soldier from the Mohawk Valley (perhaps free, perhaps enslaved), he represents hundreds of others who fought for either the British or the Americans in the Revolutionary War in this area. He also represents the many people—Native, African, or European—who intermarried with people of a different ethnic background. In Bakeman’s case, he married a woman of Dutch descent. Their descendants still live in central New York today, some identifying with their African background, some with their European heritage, and some recognizing both.19

Out of this multicultural mix of Native Americans, Europeans, and people of African descent came a new country, forged in the crucible of the American Revolution. The young Republic was on the brink of revolutions in transportation, industry, and settlement patterns, but it was still plagued by the curse of slavery. In Oneida County and elsewhere, some Americans of all ethnic backgrounds resisted enslavement of themselves and others. They built on the ideal of equality to organize both for the abolition of slavery and, through the Underground Railroad, the immediate freedom of those already enslaved.20

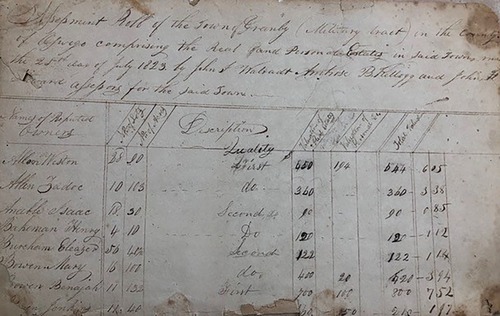

Below: An image of records from the Town of Granby, NY showing Henry Bakeman as a resident on the "Military Tract."

All text as excerpted from: “We Took to Ourselves Liberty”: Historic Sites Relating to the Underground Railroad, Abolitionism, and African American Life in Oneida County and Beyond. Judith Wellman, Principal Investigator, with Jan DeAmicis, Mary Hayes Gordon, Jessica Harney, Deirdre Sinnott, and Milton Sernett. Prepared under a cooperative agreement between The Organization of American Historians and the National Park Service January 2022.

Citations:

- Michael Lee Lanning, African Americans and the Revolutionary War (New York: Kensington, 2000), 73–86, and Appendix H, “The Rhode Island Slave Enlistment Act, February 14, 1778.” Reference to New York State law comes from James Kent and William Lacy, Commentaries on American Law 2 (Blackstone, 1889), Kindle locations 7379–7391; Quarles, Negro in the American Revolution, 56; McManus, Slavery in New York, 157. The sixth section of this Act read: “Any person who shall deliver one or more of his able-bodied servants to any warrant officer … shall, for every male so entered and mustered as aforesaid, be entitled to the location and grant of one right, in manner as in and by this act as directed; and shall be, and hereby is discharged from any further maintenance of such slave. … And any such slave so entering as aforesaid, who shall serve for the term of three years or until regularly discharged, shall, immediately after such service or discharge, be, and is hereby declared to be, a free man of this State.” Noted in Joseph Thomas Wilson, The Black Phalanx: A History of the Negro Soldiers of the United States in the War of 1775–1812, 1861–’65 (American Publishing Company, 1888), Kindle edition, 56–57, Kindle location 766.

- “Historical and Biographical Sketch of Henry Bakeman (also spelled Bateman) a Revolutionary War Soldier,” November 16, 1912, from a Daughters of the American Revolution scrapbook kept by Mrs. Schenck, Fulton Public Library, Fulton, New York. Thanks to Peter Palmer for finding this. Bakeman’s birthplace is listed in several sources as Rocky Hill, Somerset County, either in New Jersey or New York. There is no Somerset County in New York State, but there is a Rocky Hill in Orange County, along the Hudson River. A migration pattern from mid-New Jersey to the Mohawk Valley would have been an unusual pattern. See also Henry Bakeman, Pension Record, National Archives and Records Administration.

- Larry Lowenthal, Marinus Willett: Defender of the Northern Frontier (Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press, 2000), 48–49, 59.

- For more on the destruction of Stone Arabia in October 1780, see “Path through History, Mohawk Valley Region, Stone Arabia Battlefield,” https://www.mohawkvalleyhistory.com/destinations/listing/Battle-of-StoneArabia

- Lowenthal, Marinus Willett, 74.

- Robert A. Geake and Loren M. Spears, From Slaves to Soldiers; Michael Lee Lanning, African American in the Revolutionary War (Kensington, 2000), 73–86, estimates that the First Rhode Island never had more than 140 men of color. Van Buskirk, “A Bold Experiment in Rhode Island,” Standing in Their Own Light, 95–141. This narrative of the 1783 expedition is based primarily on Lowenthal, Marinus Willett, 72–75, and on Henry Bakeman’s account, given in his pension record (NARA). Geake and Spears dealt with this 1783 expedition briefly (From Slaves to Soldiers, 85). Lanning mentioned it only in passing. Berleth mentioned neither the First Rhode Island Regiment nor the Oswego expedition.

- Lowenthal, Marinus Willett, 72–75; Henry Bakeman, pension record (NARA).

- Henry Bakeman, Revolutionary War Pension, National Archives and Records Administration, also available in Fold 3; “Henry Bakeman,” November 16, 1912, clipping from in Mrs. Schenck’s Daughters of the American Revolution scrapbook, 1902-ff, Fulton Public Library. Many thanks to Peter Palmer for finding this.

https://catalog.archives.gov/id/53866280

- Geake and Spears, From Slaves to Soldiers, 71.

- Henry Bakeman, Pension.

- We have considerable evidence about Bakeman, including a biography in a 1912 Daughters of the American Revolution publication, pension records, marriage records, deeds, a statement affirming his free status in 1819, and a reference in Landmarks of Oswego County (1895). Thanks to Barbara Bakeman Fero and Joanne Bakeman, descendants, for sharing their amazing stories, and to Peter Palmer and John Snow for sharing sources they found. “Dutch Reformed Church Records in Selected States, 1639–1989 for Henry Beckman,” Ancestry.com.

- It is possible that Bakeman also owned land in Somerset County, New Jersey. Tax records in Bridgewater Township, Somerset County, New Jersey, for June 1792 and September 1808 listed a “Henry Beckman” as the owner of land. New Jersey Tax Lists Index 1772–1822, Ancestry.com.

- Deeds, Oswego County Clerk’s Office; “Land in Lysander Sold,” Oswego Palladium Times, March 30, 1820.

- “Henry Bakeman,” DAR scrapbook, 1912, in Fulton Public Library; Landmarks of Oswego County, 518–19, noted, “About 1800 a mulatto, Henry Bakeman, from New Jersey, purchased the improvements of Lay and Penoyer on Lot 4 and became a permanent resident there.” Town of Granby, “Assessment Roll, 1822, 1823, 1824,” Granby Town Supervisor’s Office. Many thanks to John Snow, Granby Town Supervisor, for locating these records.

- “Minutes,” Board of Supervisors, Town of Granby, June 1820. Many thanks to John Snow, Granby Town Supervisor, for locating these records.

- US Census, 1820, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/interactive/7613/4433229_00058?pid=306451& backurl=https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?dbid%3D7613%26h%3D306451%26indiv%3Dtry%26o_ vc%3DRecord:OtherRecord%26rhSource%3D8058&treeid=&personid=&hintid=&usePUB=true&usePUBJs=true; Judith Wellman, “Benjamin and Rachel Bakeman House,” The Underground Railroad, Abolitionism, and African American Life in Syracuse and Onondaga County, https://pacny.net/freedom_trail/Bakeman.htm.

- Henry Bakeman, pension application, from the National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Pension Records for Henry and Jane Bakeman,” National Archives; “Petition of Juliett Bakeman to Surrogate’s Court, Onondaga County, April 12, 1856”; “Henry Bakeman,” DAR scrapbook, 1912; https://www. findagrave.com/memorial/97969937/henry-bakeman.

- https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/196817623. There is a Joseph Perrigo, fifer, First Rhode Island Regiment, listed in pension records in 1831, living in Washington County, northeast of Albany, New York. He seems to have a son also named Joseph Perrigo. “US Pension Roll of 1835,” Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry. com/interactive/60514/pensionroll1835ii-003311?pid=40307&backurl=https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse. dll?indiv%3D1%26dbid%3D60514%26h%3D40307%26tid%3D%26pid%3D%26usePUB%3Dtrue%26_phsrc%3DxdO694%26_phstart%3DsuccessSource&treeid=&personid=&hintid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=xdO694&_phstart=successSource&usePUBJs=true.

- Many thanks to Jo Anne Bakeman and Barbara Bakeman Fero, descendants of Henry Bakeman, for sharing their stories.