Last updated: April 14, 2021

Article

Partner Project Spotlight: Dam Removal on White Clay Creek

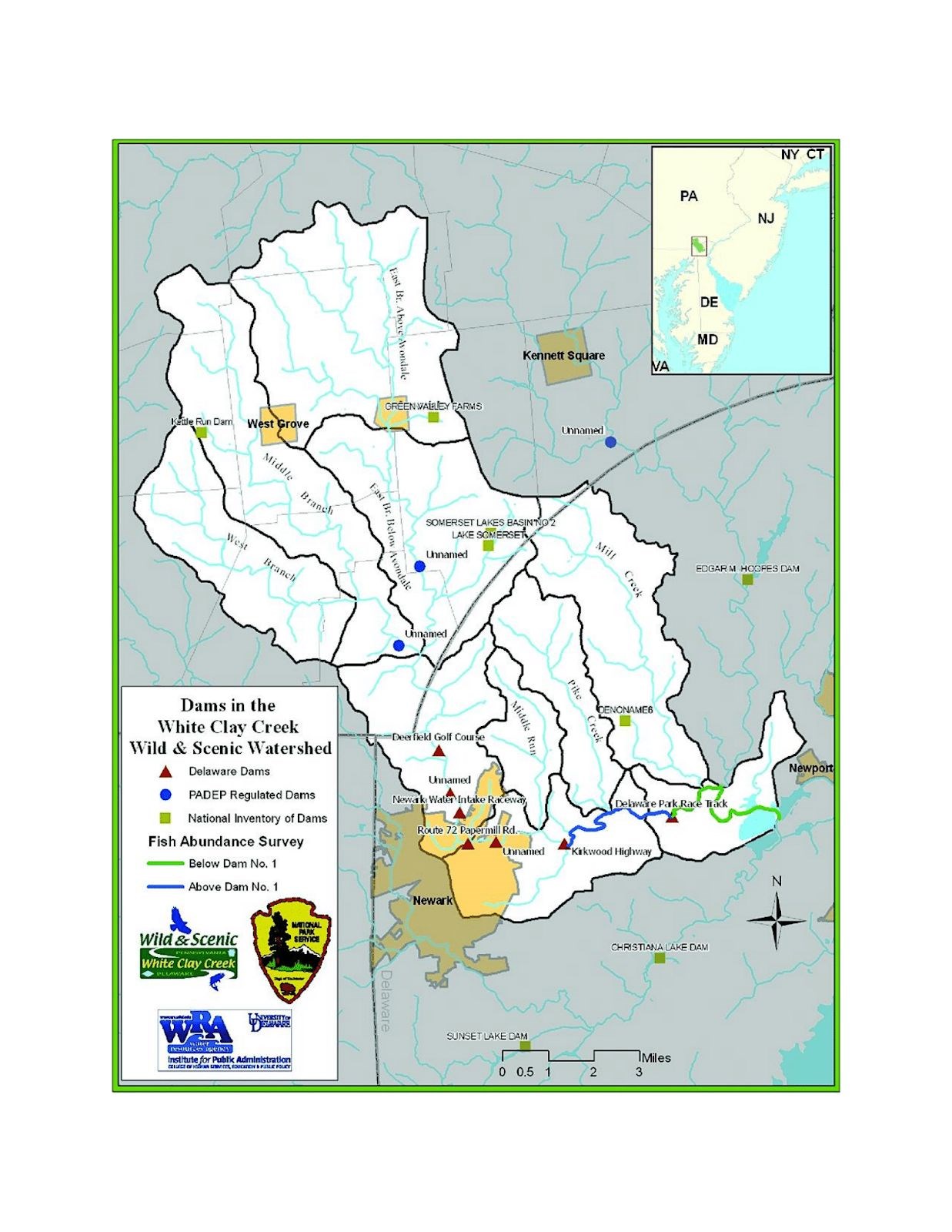

Across the country, efforts have been underway to remove dams that have outlived their intended purpose and have detrimental ecological effects or pose a safety hazard. On White Clay Creek (WCC) Wild and Scenic River, the successful removal of the first of seven dams has opened the way for improved ecosystem health and fish passage.

The Wild and Scenic Rivers Acts provides provisions for rivers with existing low dams, as long as no further construction of these structures occur, and with guidance to ‘protect and enhance river values’, including free flow. The White Clay Creek (WCC) Wild and Scenic River had one of the country’s first dams, installed in 1777. Nearly 250 years later, a collective effort was underway to successfully remove the first of seven dams on WCC to improve ecosystem health and fish passage.

Jerry Kauffman, Assistant Professor and Director of the Water Resources Center at the University of Delaware, was integral to this process. Dam #1 on WCC, one of the country’s first (built in 1777), was the site of the first dam removal project in Delaware, opening up 4.8 miles for fish passage and allowing shad allowing shad (an important anadromous fish species) to travel up the White Clay Creek for the first time since 1777. Shad returned to the Creek within 1-2 years after dam removal!

Jerry states, “My office is in the Water Resources Center at the University of Delaware and the White Clay Creek flows right through the middle of campus. We were called in by the National Park Service to help assemble the document that became the basis for designating the White Clay Creek as a National Wild and Scenic River…and in 2000, [it] was designated.”

“In the Management Plan there was a section that recommended taking action to make the White Clay Creek truly free-flowing; [flow was impeded in WCC by] the seven dams in Delaware and several in Pennsylvania. In 2008, there was a feasibility study to see if these dams could be removed…In 2011, we started to take the actions and get the permits for the removal of Dam #1,” Jerry explained.

There’s a lot at play in the White Clay. Fish, water quality, and history are all major aspects of this river’s character. Gaining clean enough water quality for fish to return and thrive is a long process. Some dams, such as Dam #2 are associated with the National Register of Historic Places. Sec 106 of the Cultural Resources Act requires approval from the Secretary of the Interior if they are to be altered. Jerry explained that some of the history on the White Clay has been traditionally overlooked.

“We’re learning that we’re not covering enough of [the living history of] Indigenous people of America. We’re assuming history started with the Europeans. The Dam at Red Mill was installedin the late 18th Century, but there’s a history that goes back millennia.”

The removal of Dam #1 and the ecological and historical restoration efforts of that removal would not have been completed without Jerry’s diligence and commitment to the project, as well as strong partner organizations such as: the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the Brandywine Conservancy, the City of Newark and the Christina Basin Clean Water Partnership.

Since Jerry has shifted his efforts to dam removal on the Brandywine, Jason Fischel and Matthew Fischel have been pivotal in creating more sections of White Clay Creek free-flowing. These brothers are both Postdoctoral Research Fellows at the University of Delaware with PhDs in soil chemistry.

“We love to bike and hike at White Clay. And when we were growing up, around high school, there was all this information about restoring shad, and the dam removal movement was really growing, which always kept dams in our realm of thought,” said Jason. Both he and Matt are working on efforts to remove Dams #2 and #4 (the Dams are numbered from the Delaware River upstream).

Jason was encouraged to apply for funding to remove Dam #2 on White Clay Creek after working as a science liaison with State Senator Chris Coons. This funding built momentum and formed relationships between partner organizations that led to a plan for the removal of the Dam #2.

The team was just officially informed that they have received funding to take out the fourth of six dams left on the White Clay Creek in Delaware. “The city of Newark is building a pedestrian bridge across the White Clay adjacent to Dam #4. This will be a part of a series of rail trails that weave their way through the City… So now we have an agreement and contribution from the City of Newark to help remove this dam, and hopefully next summer the Dam #2, Red Mill Dam, and Dam #4, the Paper Mill Dam, will both come out,” Jason explained.

Matt went on to say how this project has been a sort of childhood dream come to fruition. “We grew up going to a lot of these streams like the Red Clay, the White Clay, the Brandywine, and when we were younger we would talk about, ‘ Oh it would be so awesome if there were less dams, you could go tubing and kayaking and canoeing .’ And then when Jason had the opportunity to apply for this grant, we were able to help that dream come true a little bit for at least one river in Delaware.”

Matt went on to say that the dam removal process has been met with support and excitement. “Overall most people, I think especially anyone who knows about water quality and anything environmental, understand the importance of dam removal, from both the recreation and ecosystem perspective.”

Some of the greatest excitement has come from anglers of all ages, especially families who enjoy going to the river together. Matt and Jason’s family would take fly-fishing trips and would often see hundreds of shad and various other species on their trips. “It made you realize, ‘ Oh wait these could be in all the rivers around us too, but dams are preventing them .’ So it would be really cool to see them come back,” Matt reminisced.