Part of a series of articles titled Park Paleontology News—Vol. 17, No. 2, Fall 2025.

Article

Paleontology of Morrison–Golden Fossil Areas National Natural Landmark

Photo courtesy of Dinosaur Ridge/Amy Atwater

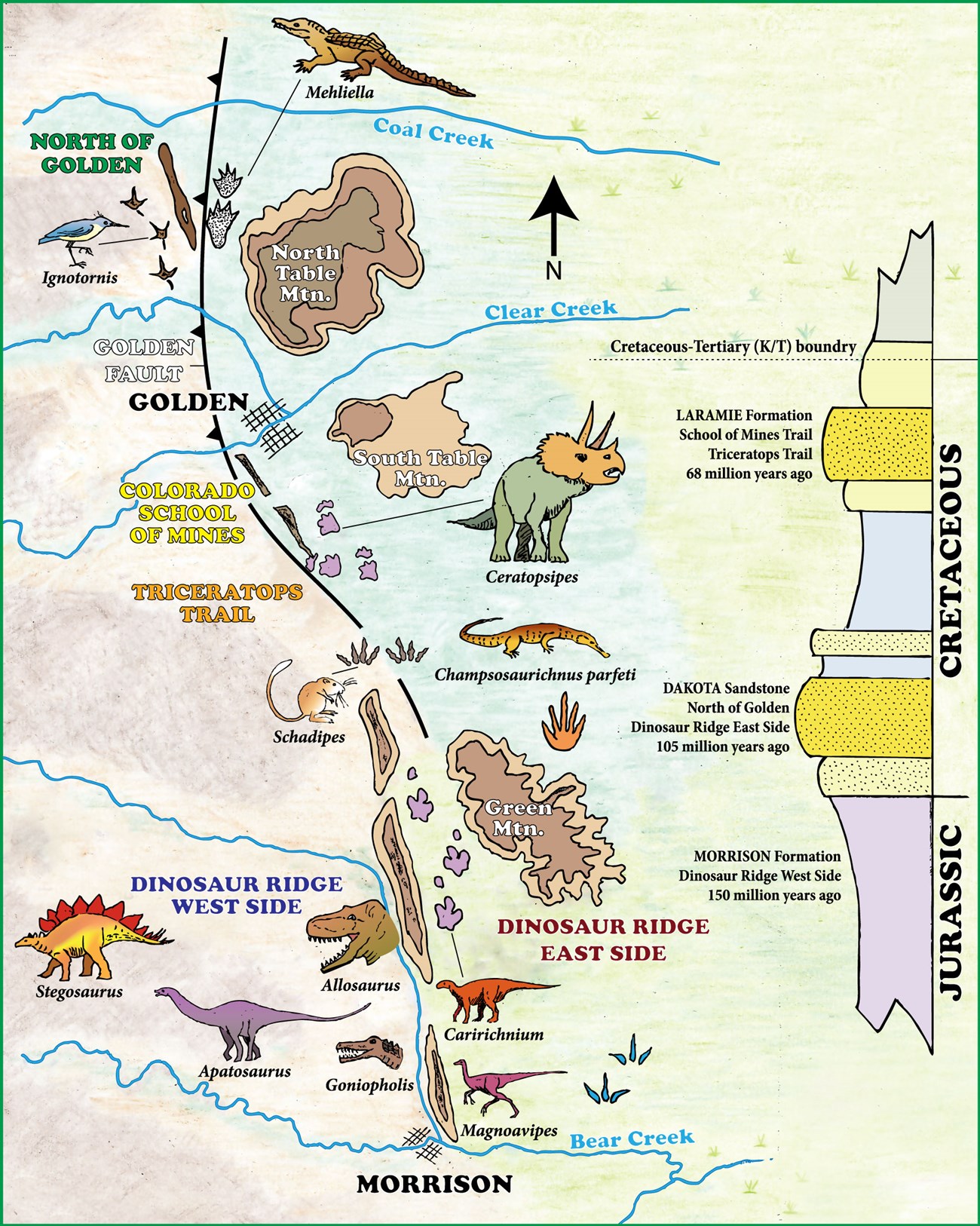

Map by Martin Lockley, courtesy of Dinosaur Ridge/Amy Atwater

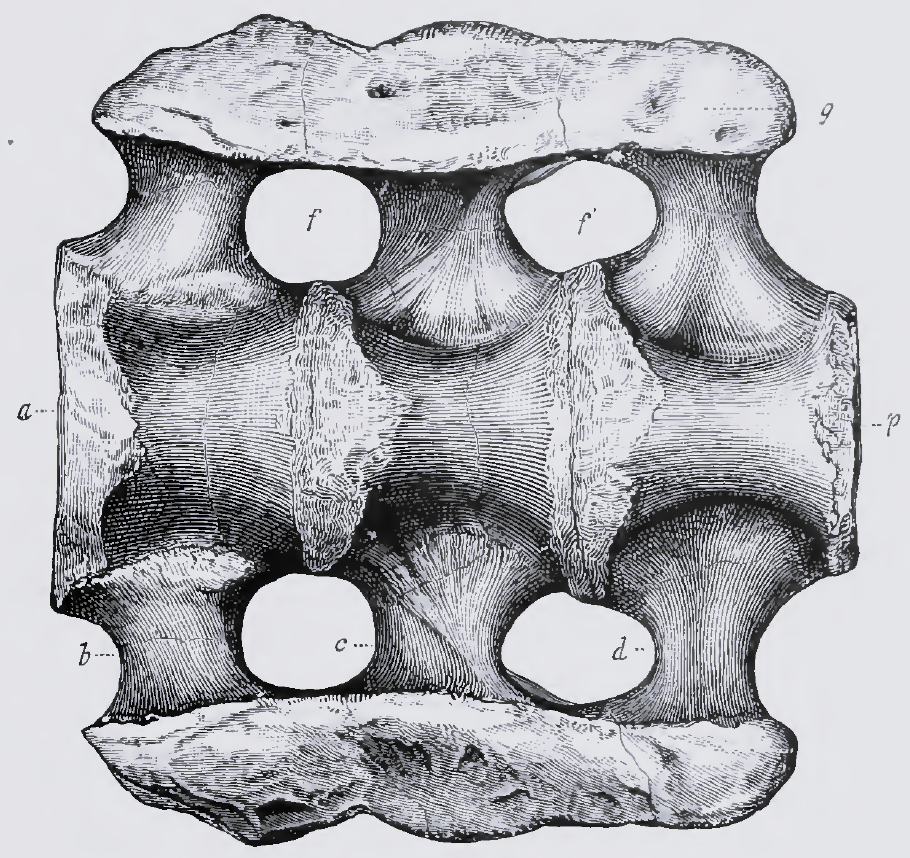

American Journal of Science

Photo courtesy of National Natural Landmarks Program/Deborah DiQuinzio

Photo courtesy of Dinosaur Ridge/Amy Atwater

The geologically youngest parts of Morrison–Golden Fossil Areas NNL are the Colorado School of Mines tract and Triceratops Trail. Both of these tracts are located within Golden in the Laramie Formation, which was deposited on a coastal plain shortly before the end of the Cretaceous. Both have abundant tracks of dinosaurs and other animals, as well as plant fossils. Unlike the typical fossil site, Triceratops Trail is located within a golf course. The fossils here were first discovered when the area was used as a clay quarry. After quarrying operations ended and work began for the golf course, some of the land was used to preserve the fossils.

Photo courtesy of Dinosaur Ridge/Amy Atwater

Photo courtesy of Dinosaur Ridge/Amy Atwater

Administered by the National Park Service, the National Natural Landmarks Program recognizes and supports the voluntary conservation of exemplary biological and geological sites that illustrate the nation’s natural heritage, including those that contain significant paleontological resources. National natural landmarks are designated by the Secretary of the Interior and are owned by a variety of public and private stewards. To date, significant paleontological resources have contributed, in whole or in part, to the designation of 58 National Natural Landmark sites across the country, and paleontological resources are known at many others as well. These landmarks represent the range of geologic history from very early marine life 510 million years ago to more recent (40,000 years ago) fossil mammals.

Photo courtesy of Dinosaur Ridge/Amy Atwater

Morrison Fossil Area

has been designated a

National Natural Landmark

This site possesses exceptional value

as an illustration of the nation's natural

heritage and contributes to a better

understanding of the environment

1975

National Park Service

United States Department of the Interior

Last updated: October 1, 2025