Part of a series of articles titled Park Paleontology News - Vol. 14, No. 1, Spring 2022.

Article

Painting the Stories of the Past at Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument

Lauren Parry

Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument

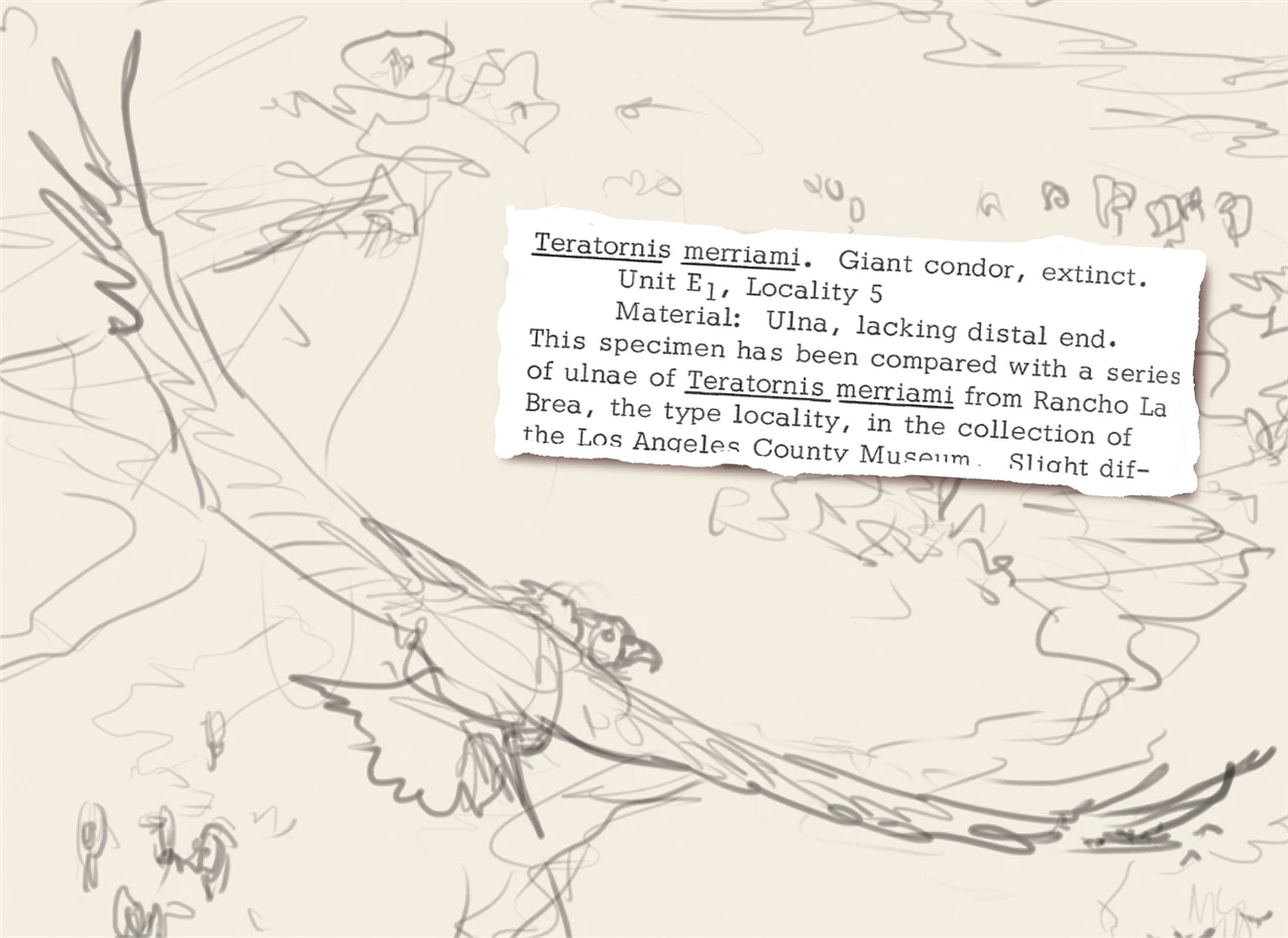

Decades of research and investigation have uncovered a compelling and detailed story about change, struggle, and survival at Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument in Las Vegas, Nevada. Clues from the rock and fossil records are found in a library of publications, but art can be a powerful way to share these stories and inspire people to learn about the past. An interdisciplinary team of researchers and National Park Service staff came together with renowned paleoartist Julius Csotonyi to depict four snapshots of life at Tule Springs Fossil Beds throughout the Pleistocene epoch.

During the Pleistocene, groundwater springs appeared on the landscape of Tule Springs as marshes, pools, streams, and wet meadows that trapped windblown sand and mud. The resulting sedimentary deposits also preserve periods of drying, erosion, and soil formation, indicating that these desert wetlands responded to global glacial and interglacial periods. These wetlands were rich habitats for Ice Age animals between approximately 100,000–12,500 years ago. Since then, several of the species have gone extinct, disappearing from North America entirely; others sought refuge in the highlands or more isolated spring environments; and some adapted to their changing environment and have remained at Tule Springs for more than 14,000 years.

In paleontology, we use the familiar to aid our imaginings of the unknown. Despite obvious differences in the local habitat, Dr. Csotonyi wants viewers to notice details that are part of today’s world: “The aim is to be able to recognize this environment.” While planning the content and layout of these paintings, the collaborative team looked to the behaviors of wild animals and even their own pets. In portraying now-extinct animals, he “[tries] to imagine them overlaying the patterns of behaviors of living animals.” The extinct carnivores of Tule Springs, such as saber-toothed cats and American lions, were fierce predators, but they likely spent most of their day lounging and grooming.

Each of the four “snapshots” began as a compilation of the rock, fossil, and pollen records of distinct geologic units of the Las Vegas Formation at Tule Springs. Bringing these scenes to life was “an interesting challenge” to Dr. Csotonyi, “to try to effectively get in everyone’s head”, from depicting Pleistocene plant communities to determining appealing color palettes. He sees paleoart as a way to effectively engage people with scientific findings: “Not only does it overcome the language barrier, but it also works in a way to inspire young people to gain an interest in the field and that inspiration is extremely important.

Images: (left) NPS Image; Julius Csotonyi; (right) Image courtesy of Eric Scott, Cogstone Resource Management.

NPS Image; Julius Csotonyi; Inset text from Mawby (1967).

NPS Image; Julius Csotonyi.

The paleontological story of Tule Springs Fossil Beds speaks to how much can change in a geologically short period of time, but it also shows the longevity of certain species in this environment. Fossil specimens from coyotes (Canis latrans), kangaroo rats (Dipodomys sp.), jackrabbits (Lepus sp.), and hawks (Buteo sp.) are found in Tule Springs museum collections alongside mammoth teeth and camel leg bones (Camelops hesternus). As an ecologist, Dr. Csotonyi hopes paleoart will inspire people to learn about the paradoxical fragility and longevity of different species over time: “When we’re outside, observing living animals or plants, and seeing them move, we can take it for granted… You need time to have some predictive power.” Inspiring people to care about the past also empowers them to care about the future. What we learn from the fossil record can help protect biodiversity today at National Parks and ecosystems across the world.

These four paintings by Julius Csotonyi will be featured in a traveling museum exhibit developed by Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument. For exhibit inquiries, please contact the park.

Related Links

- Tule Lake National Monument—[Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home] [npshistory.com]

- NPS—Fossils and Paleontology

- NPS—Geology

Last updated: March 31, 2022