Last updated: January 12, 2023

Article

How Connected is the Landscape at Valles Caldera?

The connectivity of a landscape is important because the more connected and intact a landscape is, the greater the opportunity for movement of species, populations, and genes among habitat patches. This is vital, for example, to allow individual organisms and populations to move among areas of suitable habitat for seasonal migrations, for dispersal (such as an animal’s movement away from where it was born), and for moving into new habitat. Landscape connectivity is and will be critical for ecosystems and species to adapt to climate change, such as by enabling a species to shift its range to areas with more suitable temperatures.

A loss of connectivity can effectively reduce the size and quality of available habitats and disrupt movements, potentially leading to negative effects on populations and species, including population declines and loss of genetic variation.

Threats to landscape connectivity

Worldwide, connectivity of the landscape is threatened due to fragmentation of habitat (breaking it up into smaller or more isolated pieces), degradation of habitat, and habitat loss (the destruction of habitat). Connectivity and, therefore, wildlife movements across the landscape are disrupted by human land uses and activities, such as developed areas, roads, croplands, energy development, and more. Within Valles Caldera, roads and structures like fences disrupt connectivity.

Connectivity can also be improved by removing or retrofitting human infrastructure to reduce barriers. For example, staff at Valles Caldera have been removing unneeded fences in the preserve for years, as well as converting those that are needed to more wildlife-friendly fences.

Focusing on landscape connectivity at Valles Caldera

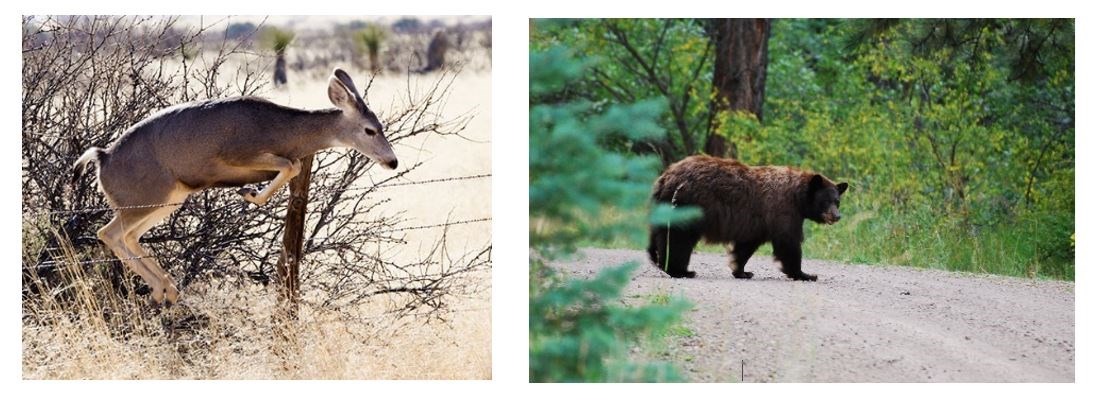

Valles Caldera National Preserve is an 88,900-acre (35,977 hectares) national park unit in the Jemez Mountains of New Mexico. Ecosystem types within the preserve include upper montane, lower montane, shrubland, grassland, and valley bottom/riparian. These ecosystem types provide habitat to a wide variety of plants and animals, including elk, deer, bear, mountain lions, birds, and endangered species (such as the New Mexico meadow jumping mouse and the Jemez Mountains salamander).

As part of a recent Natural Resource Condition Assessment (NRCA) at Valles Caldera, we assessed landscape connectivity to better understand connectedness among the patches of major ecosystem types and within the overall landscape. NRCAs, through the NPS NRCA Program, evaluate natural resource conditions so that parks can use the best available science to manage their resources.

To assess landscape connectivity, scientists used models to assess the conditions of two measures—ecosystem connectivity (or permeability) and landscape connectivity. The study area was about 31 miles wide and encompassed about 3,860 square miles in northern New Mexico, centered on Valles Caldera National Preserve.

- Ecosystem connectivity measures the connectivity of the study area as the probability of reaching a specific ecosystem within different dispersal distances—6.2 miles (10 kilometers [km]), 18.6 miles (30 km), and 31.1 miles (50 km) in this assessment.

- Landscape connectivity measures the connectivity of the study area as the probability of reaching all ecosystems within the three different dispersal distances.

What did we learn?

Note that condition ratings, reported below, can range from good to poor. From our analysis, we concluded that:

- Ecosystem connectivity is good for upper montane habitats.

- Ecosystem connectivity is good/fair for lower montane and riparian/valley bottom habitats.

- Ecosystem connectivity is fair/poor for shrubland and grassland habitats.

- Landscape connectivity is fair/poor. The preserve is centered within a highly connected landscape, but connectivity gradually decreases away from the preserve’s boundary, with larger declines in the eastern portion of the entire study area.

Recommended steps to further refine the analysis include determining locations of small but important human structures and activities (e.g., wildlife-proof fencing), and, in some cases, the vegetation composition and structure within the ecosystems.

How can we use this information?

Photo: NPS/Mark Peyton.

Information from the assessment will help with planning and management for maintaining and improving habitat connectivity in the preserve and the larger landscape. This increased connectivity will facilitate the critical movements of species and help ensure resilience in the face of worldwide threats (including climate change). Results of the assessment have led to important findings, including:

- Management actions that maintain upper montane habitat, with its high elevation, will contribute to potential climate adaptation of both upper and lower montane-associated species.

- There is a patch of upper montane habitat to the northwest of the preserve that is surrounded by a highly connected landscape (including within the preserve, especially Redondo Peak). This is an important area to protect to maintain montane species’ movements, especially those for which the connectivity of shrublands and grasslands is important to reach higher elevations (such as mule deer and elk).

- Connectivity is high in the north-central area of the preserve, particularly for species associated with shrubland and riparian and valley bottoms. This level of connectivity contributes to this area’s importance within the preserve.

- Connectivity results can be combined with other park spatial datasets to inform several management actions.

- Overlay them with locations of wildlife-proof fencing and under- and/or over-passes to further refine the locations of high connectivity, and/or to identify areas to restore connectivity and remove or retrofit human modifications.

- Identify areas within the riparian/valley bottom ecosystem with high permeability that need riparian restoration and are potential New Mexico meadow jumping mouse habitat.

Information in this article was summarized from Albright J and Others. 2022. Natural resource conditions at Valles Caldera National Preserve: Findings & management considerations for selected resources. Natural Resource Report. NPS/VALL/NRR—2022/2409. National Park Service. Fort Collins, Colorado. https://doi.org/10.36967/nrr-2293731