Last updated: September 15, 2022

Article

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Colorado National Monument

Jointed goatgrass. USDA-APHIS.

What Are Invasive Exotic Plants?

Invasive exotic plants (IEPs) are non-native species whose introduction to an environment causes (or is likely to cause) economic or environmental harm, or harm to human health. IEPs can alter ecosystems at multiple scales—threatening wildlife, natural landscapes, and recreational opportunities. They can reproduce prolifically, rapidly colonize new areas, and displace native species.

Invasive plants fill different ecological roles than the native plants they replace. As a result, the needs of species that depended on the native vegetation may go unmet, potentially creating a cascade of ecological effects.

The good news is that if discovered before they have a chance to take hold, IEP populations can be eradicated from parks. Small populations are cheaper and easier to control than large populations. Therefore, early detection is critical.

What Can Be Done?

Small IEP populations are cheaper and easier to control than large populations. Therefore, early detection is critical. To help park managers prioritize control efforts, the Northern Colorado Plateau Network (NCPN) monitors invasive exotic plants in eight National Park Service units. First, network and park staff create a list of priority IEPs for each park. Then, on a rotating schedule, a field crew looks for those IEPs along established monitoring routes. Along the routes, they stop and set up plots for additional data collection. The plot data allow network ecologists to estimate trends over time.

Recent Monitoring at Colorado National Monument

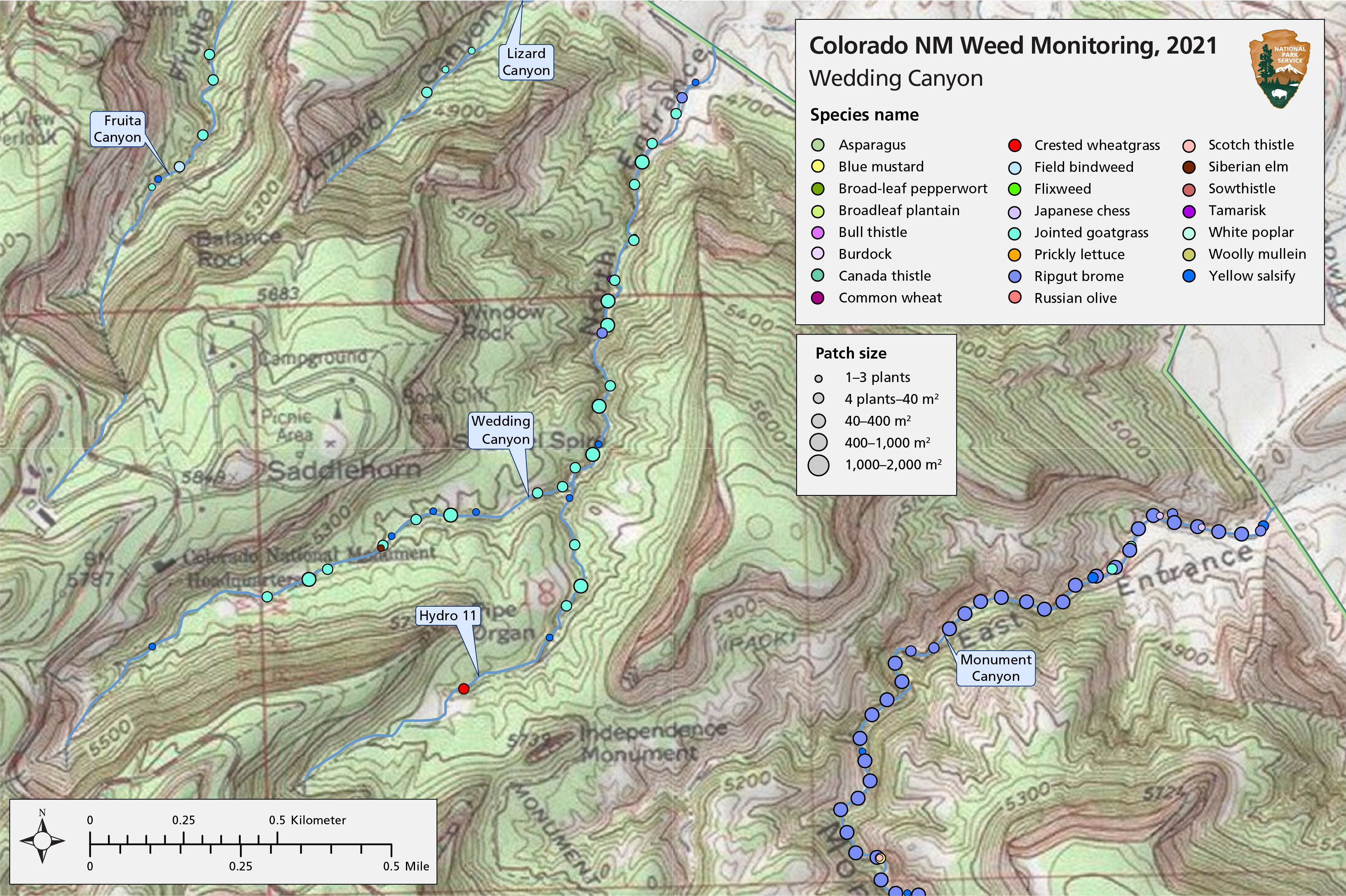

During monitoring on June 9–15, 2021, a total of 15 priority IEP species in 395 patches were detected on 53.6 kilometers (33.3 mi) of monitoring routes at Colorado National Monument (see table). An additional four species were detected in transects. Eight non-priority species were recorded.

| Scientific name | Common name | Patches |

|---|---|---|

| Tragopogon dubius | yellow salsify | 137 |

| Anisantha diandra | ripgut brome | 84 |

| Cylindropyrum cylindricum | jointed goatgrass | 42 |

| Tamarix sp. | tamarisk | 30 |

| Verbascum thapsus | woolly mullein | 28 |

| Ulmus pumila | Siberian elm | 26 |

| Convolvulus arvensis | field bindweed | 15 |

| Elaeagnus angustifolia | Russian olive | 11 |

| Cardaria latifolia | broad-leaf pepperwort | 9 |

| Breea arvensis | Canada thistle | 4 |

| Chorispora tenella | blue mustard | 2 |

| Cirsium vulgare | bull thistle | 2 |

| Descurainia sophia | flixweed | 2 |

| Onopordum acanthium | Scotch thistle | 2 |

| Arctium minus | burdock | 1 |

| All priority species | – | 395 |

Yellow salsify. Photo by Bruce Bosley, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org.

Yellow salsify. Photo by Bruce Bosley, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org.Yellow salsify (Tragopogon dubius), ripgut brome (Anisantha diandra), jointed goatgrass (Cylindropyrum cylindricum), and tamarisk (Tamarix sp.) were the most commonly detected priority IEPs along monitoring routes, representing 74% of all priority patches. Except for ripgut brome and broad-leaf pepperwort (Cardaria latifolia), most patches of priority IEPs were less than 40 m2. Three priority invasive tree species were detected: Russian olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia), tamarisk, and Siberian elm (Ulmus pumila).

Cheatgrass (Anisantha tectorum) was the most common IEP in transects, found in >63% of transects along every route surveyed.

Priority IEPs were found in highest numbers along the Red Canyon (1.29 patches/100 m), Monument Canyon (1.25 patches/100 m), Hydro 82 (1.06 patches/100 m) and Wedding Canyon (1.02 patches/100 m) routes. There were no IEP patches recorded on the Hydro 88, Limekin Gulch, or Kodels Canyon routes.

During the entire monitoring period (2005–2021), Red Canyon, Wedding Canyon, and Fruita Canyon all had the highest number of IEPs per 100 meters. Increases were driven by jointed goatgrass on all three routes, by yellow salsify in Wedding Canyon, and tamarisk in Red Canyon.

Jointed goatgrass and ripgut brome were the species found most frequently along the Wedding Canyon monitoring route.

Management Recommendations

Key findings

- Jointed goatgrass has increased rapidly since the last monitoring visit and should be targeted for control.

- Four IEPs were found for the first time in 2021. Controlling them soon could prevent widespread establishment.

- Japanese chess (Bromus japonicus) could be considered as a transect species for future visits.

- It will be much easier for park staff to contain invasive species if eradication efforts continue.

Jointed goatgrass appears to be rapidly expanding, increasing from 8 patches in 2019 to 42 patches in 2021 (though the routes surveyed were not all the same). Even many of the routes that remained relatively stable had 0–2 patches of goatgrass in 2021. This species has increased rapidly since the last monitoring visit and should be targeted for control.

In 2021, Scotch thistle (Onopordum acanthium) was found for the first time in our monitoring, in two patches in Monument Canyon. Broad-leaf pepperwort, Canada thistle, and bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare) were recorded for the first time since 2012, 2015, and 2015, respectively. All of these species are currently isolated and occurring in 10 patches or fewer. Controlling them soon could prevent widespread establishment.

Ninety-five percent of tree patches were classified as seedlings or saplings, which require less effort to control than mature trees.

Ripgut brome, added to the priority list in 2019, already represents one of the most common IEPs detected during monitoring. This species may be too widespread to be controlled.

Japanese chess (Bromus japonicus) was noted to be widespread by the field crew and could be considered as a transect species for future visits.

It will be much easier for park staff to contain invasive species if eradication efforts continue. In just a few years, small patches could become large, and seedlings and saplings will become mature trees, requiring removal by chainsaw instead of loppers or pruning shears. Preventing additional exotic-species invasions should give native species a better chance to persist.

For more information, see DW Perkins, Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring in Colorado National Monument: 2021 Field Season.