Last updated: September 4, 2022

Article

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Colorado National Monument, 2019

What Are Invasive Exotic Plants?

Invasive exotic plants (IEPs) are non-native species whose introduction to an environment causes (or is likely to cause) economic or environmental harm, or harm to human health. IEPs can alter ecosystems at multiple scales—threatening wildlife, natural landscapes, and recreational opportunities. They can reproduce prolifically, rapidly colonize new areas, and displace native species.

Invasive plants fill different ecological roles than the native plants they replace. As a result, the needs of species that depended on the native vegetation may go unmet, potentially creating a cascade of ecological effects.

The good news is that if discovered before they have a chance to take hold, IEP populations can be eradicated from parks. Small populations are cheaper and easier to control than large populations. Therefore, early detection is critical.

What Can Be Done?

Small IEP populations are cheaper and easier to control than large populations. Therefore, early detection is critical. To help park managers prioritize control efforts, the Northern Colorado Plateau Network (NCPN) monitors invasive exotic plants in eight National Park Service units. First, network and park staff create a list of priority IEPs for each park. Then, on a rotating schedule, a field crew looks for those IEPs along established monitoring routes. Along the routes, they stop and set up plots for additional data collection. The plot data allow network ecologists to estimate trends over time.

During data analysis, a Patch Management Index (PMI) helps identify the scale of the problem presented by each patch of exotic plants. PMI multiplies the size of each patch by the amount of each patch that is covered in weeds to arrive at a composite score. The PMI score is assigned to a class, ranging from very low to very high.

To be useful, PMI must be considered in combination with species and patch numbers. In many cases, targeting patches with very low or low PMI allows managers to keep small patches from growing into bigger problems. On the other hand, a species with many patches of very low or low PMI may be harder to treat than a different species with just a few patches of high or very high PMI.

Recent Monitoring at Colorado National Monument

At Colorado National Monument, the NCPN monitors a combination of standard monitoring routes and transects and “extra areas” of management interest to park staff. During monitoring on June 12–19, 2019, a total of 20 IEP species were detected on monitoring routes and transects. Of these, 12 were priority species that accounted for 791 separate IEP patches (see table). IEPs were most prevalent along riparian areas.

| Scientific name | Common name | Patches |

|---|---|---|

| Melilotus officinale | yellow sweetclover | 356 |

| Tragopogon dubius | yellow salsify | 218 |

| Descurainia sophia | flixweed | 75 |

| Verbascum thapsus | woolly mullein | 35 |

| Chorispora tenella | blue mustard | 29 |

| Convolvulus arvensis | field bindweed | 26 |

| Tamarix sp. | tamarisk | 20 |

| Ulmus pumila | Siberian elm | 12 |

| Cylindropyrum cylindricum | jointed goatgrass | 8 |

| Anisantha diandra | ripgut brome | 6 |

| Elaeagnus angustifolia | Russian olive | 5 |

| Cardaria sp. | whitetop | 1 |

| All priority species | 791 |

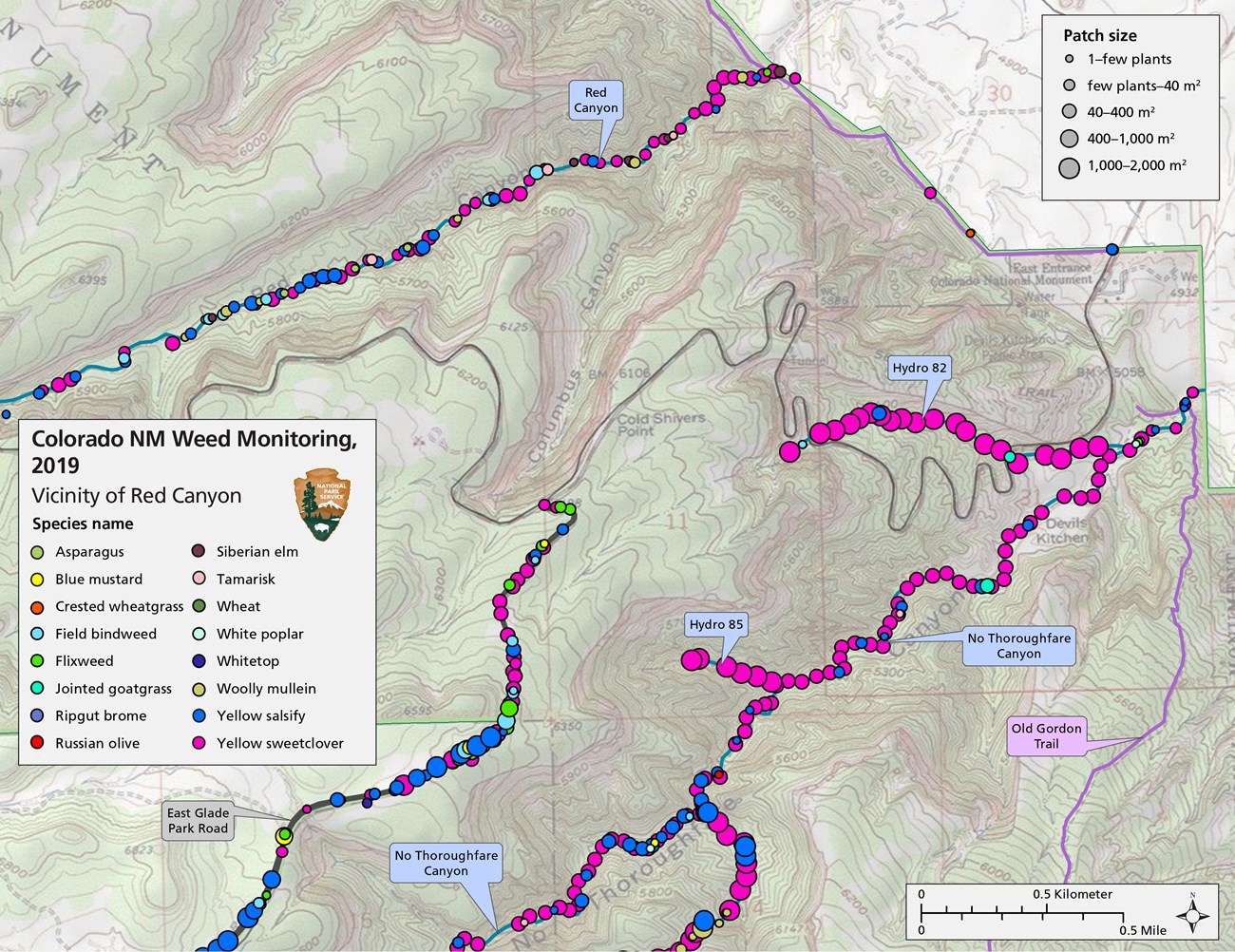

Yellow sweetclover (Melilotis officinale) and yellow salsify (Tragopogon dubius) were the most commonly detected priority IEPs along monitoring routes, representing 73% of all priority patches (see map). In general, the number of IEP patches per 100 meters on monitoring routes has increased or remained constant over the last 10 years. There were notable increases in the number of IEP patches per 100 meters on several routes in 2019.

Cheatgrass (Anisantha tectorum) was the most common IEP recorded in plots, found on 30–77% of transects across the different routes.

When treated and untreated extra areas near the West Entrance were compared, the treated area had comparable or higher levels of IEPs than the untreated area. This may be because new invasives are filling in behind the controlled species faster than native species are.

Management Recommendations

In 2019, a large majority of priority IEP patches were assigned a PMI score of low or very low, indicating small and/or sparse patches where control is generally still feasible. Cheatgrass and yellow sweetclover are widespread across the park but sparsely dispersed within patches, making future control efforts difficult.

However, six of the twelve priority IEP species observed across the park were found to have 25 patches or fewer. These species should be targeted for control efforts for potential eradication along monitoring routes.

The number, size, and maturity of tree patches indicate that control efforts of woody patches along monitored routes to date have been effective and should continue. Declines observed in these populations are likely the result of efforts by park staff and volunteers to control these species. Tree patches consisted largely of seedlings and saplings, which are easier to control than mature trees. Continued control efforts should be made before more seedlings and saplings grow into mature trees.

More than half of woolly mullein patches are currently smaller than 40 m2. Because this species can be treated with hand-pulling, future control efforts by park staff and volunteers may be particularly effective. Keeping mullein at low numbers will require constant effort.

It will be much easier for park staff to contain invasive species if eradication efforts continue. In just a few years, small patches could become large, and seedlings and saplings will become mature trees, requiring removal by chainsaw instead of loppers or pruning shears. Preventing additional exotic-species invasions should give native species a better chance to persist.

For more information, see D.W. Perkins, Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring in Colorado National Monument: 2019 Field Season.