Last updated: May 9, 2024

Article

Localized Drought Impacts on Northern Colorado Plateau Landbirds

Landbirds and Climate Change

People have long relied on landbirds to warn us about environmental change (think of the “canary in the coal mine”). But in the arid American West, prolonged drought has coincided with declining numbers for many bird species in the past few decades. In the coming years, national parks of this region are projected to experience faster warming and bigger reductions in precipitation than in any other area of the US.

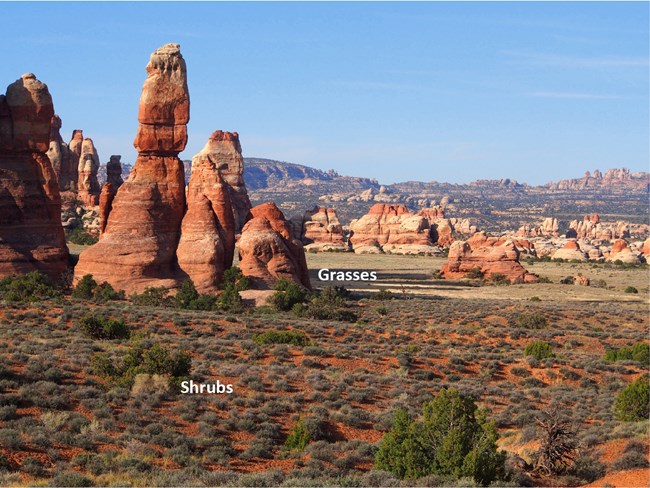

To help park managers plan for those changes, scientists from the Northern Colorado Plateau Network and University of Delaware evaluated the influence of water deficit on landbird communities at 11 national parks in Utah and Colorado. We analyzed data from breeding-bird surveys and local climate records for three habitat types over 12 years. The results will help land managers to focus conservation efforts on places where certain species are most vulnerable to projected climate changes.

At a Glance

- Birds of the desert southwest, a climate-change hotspot, are among the most vulnerable groups in the United States.

- We determined how bird communities in three habitats responded to water deficit in 11 national parks on the Northern Colorado Plateau.

- Responses depended on habitat type and species traits, demonstrating that increased drought stress is not inherently bad or good for all species. Species that breed in multiple habitats may find it easier to adapt.

- Knowing how sensitive different species are to drought stress can help land managers to focus on the habitats where certain landbirds are most vulnerable.

What is Water Deficit?

Water deficit is a measure of drought stress. In the past, drought was often thought of as below-average precipitation. But as temperature increases, so does evaporation. When above-average temperatures accompany below-average precipitation, extreme water stress can result.

As a single variable, water deficit refers to the amount of additional water vegetation would use if it was available. Similar to an overdrawn bank account, it can also be thought of as the gap between the amount of water plants need and the amount of moisture stored in the soil. Water deficit simplifies our understanding of drought stress caused by below-average precipitation, above-average temperature, or any combination of the two.

It’s also a highly localized measure. Water deficit accounts for the influence of site characteristics, such as elevation, slope, aspect, and soil type. Soil properties like texture, depth, and water-holding capacity affect how quickly soils dry. As a result, sites that share the same climate can experience different levels of water deficit.

What Does Water Deficit Have to Do with Birds?

Plants experiencing a lack of water have a harder time with growth and reproduction. This affects the foods (seeds and insects) birds eat and, eventually, the birds themselves, as the impacts move up the food chain.

On the Colorado Plateau, whether a given year is wetter or drier than normal strongly influences vegetation condition. But this area has been in a state of drought for much of the past 20 years. During the study period (2005–2015 and 2017), vegetation responded strongly to water deficit. The size of the effect varied by vegetation type, largely due to differences in soils.

The strong association between vegetation condition and water deficit allows scientists to evaluate relationships between water deficit and ecosystem parameters influenced by vegetation condition—such as bird density. The results described here represent the first attempt to determine how changes in water availability might affect aridland breeding birds in distinct vegetation types.

Some Species are Vulnerable; Others Will Adapt

We examined 30 combinations of species and habitat (riparian, pinyon-juniper, and sagebrush shrubland). Of those, 70% (n = 21) showed significant relationships between landbird density and water deficit (see table). Of those significant relationships, 38% (n = 8) were negatively related, meaning density decreased as deficit increased (less water, fewer birds). Sixty-two percent (n = 13) were positively related (less water, more birds). Some relationships were stronger than others, and some species had different responses in different habitats.

| Species | Relationship | |

|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | |

| Ash-throated flycatcher | -- | R, PJ |

| Bewick’s wren | -- | PJ |

| Dusky flycatcher | SS | -- |

| Gray flycatcher | PJ | -- |

| Gray vireo | -- | PJ |

| Green-tailed towhee | SS | -- |

| House finch | -- | R, PJ |

| Juniper titmouse | -- | PJ |

| Lark sparrow | -- | SS |

| Lazuli bunting | R | -- |

| Mourning dove | -- | R, SS |

| Sage thrasher | SS | -- |

| Spotted towhee | R, PJ | SS |

| Violet-green swallow | -- | R |

| Western meadowlark | -- | SS |

| Yellow warbler | R | -- |

R=riparian; PJ=pinyon-juniper; SS=sagebrush shrubland

Birds that became scarcer when less water was available are potentially vulnerable to climate change in the Southwest. These species may be less able to adapt to likely future scenarios than other birds. For example, the yellow warbler had a negative response to water deficit in riparian habitat, indicating high vulnerability to drought stress. Other species that seemed especially sensitive to water deficit included lazuli bunting (riparian habitat), spotted towhee (pinyon-juniper), and dusky flycatcher and green-tailed towhee (sagebrush shrubland).

Other species responded positively to water deficit, such as lark sparrow (sagebrush shrubland), ash-throated flycatcher (riparian), and house finch and gray vireo (pinyon-juniper). These species are likely less vulnerable to expected drying.

Species that breed in multiple habitats may also find it easier to adapt. Spotted towhee responded negatively to water deficit in riparian and pinyon-juniper habitats, but positively in sagebrush shrubland. These birds could shift from breeding in riparian and pinyon-juniper habitats to sagebrush shrubland as annual water deficit increases.

As climate change continues to alter the environmental conditions under which they evolved, some species will suffer. Others will thrive. The mixed responses of landbirds in the same habitat indicate that increased drought stress is not inherently bad or good for all species. Instead, it is driven by a complex suite of factors, including some not described by this work.

Continued ecological monitoring will help us to better understand the localized impacts of climate change, and identify fine-scale management options to address them. The results summarized here provide managers a clear path to developing a set of options, depending on which species and habitats they decide to focus on.

Information in this article was summarized from SG Roberts, DP Thoma, DW Perkins, EL Tymkiw, ZS Ladin, and WG Shriver. 2021. A habitat-based approach to determining the effects of drought on aridland bird communities. Ornithology 138(3):1–13.

Tags

- arches national park

- black canyon of the gunnison national park

- bryce canyon national park

- canyonlands national park

- capitol reef national park

- colorado national monument

- curecanti national recreation area

- dinosaur national monument

- fossil butte national monument

- natural bridges national monument

- zion national park

- landbirds

- landbird community monitoring

- climate change

- climate change effects

- climate change adaptation

- climate science

- research

- monitoring

- resource management

- inventory and monitoring

- ncpn

- northern colorado plateau

- northern colorado plateau network

- drought

- waterbalancecc