Last updated: December 16, 2020

Article

Native Americans and the Underground Railroad

Photo Courtesy of Dr. Tiya Miles

When an enslaved Black teenager named Michael ran from the quarters he shared with his mother in the Cherokee Nation (present-day northwest Georgia), he triggered a frantic search. Michael’s mother, Pleasant, had been purchased by the Moravian Church of Salem, North Carolina. She arrived with Moravian missionaries in 1805 when they took up their new post at the Springplace Mission near the home of wealthy Cherokee slaveholder, James Vann. Pleasant had given birth to her son along the way, but did not have the right to name him. The missionaries chose the name for her child and directed Pleasant in numerous tiring tasks at the fledgling mission. Pleasant served as an unwilling anchor of the missionaries’ church and school, for which she was the cook, cleaner, and woman of all work. As Michael grew into the physical strength of adolescence, he became more valuable to the Moravian Church and its representatives. According to the missionary diarist at Springplace, tensions with his mother led Michael to flee in May of 1819. “We had a difficult day,” missionary Anna Rosina Gambold wrote. “Our Michael got into a bad argument with his mother and it turned into a fight. We tried seriously to guide him back to his duty, but instead of doing this, he jumped up and ran away. We did not go after him because we believed he would come back in the evening, as has already happened twice, but this time he stayed away.”[1]

The missionary diarist refers to this young man in the possessive language of “our Michael” and may have been psychologically invested – consciously or not -- in blaming his mother for his departure. It is possible that frustration with his mother was indeed the spark of Michael’s anger that day, but it is just as likely that he chaffed against his proscribed “duty” and the constraints he faced while maturing into self-consciousness as the property of others. The missionaries hunted for days, but found that Michael had employed various subterfuges. He “spent the night” in the home of a Cherokee woman and told her “he was free and allowed to go wherever her wanted.” Prior to this, the Mission diarist noted, Michael had attempted to “pass as an Indian” by having “his hair cut by an Indian . . . and his face painted.” The missionaries finally enlisted the aid of a Cherokee man in recapturing Michael. The hunter found Michael on the fifth day, working in the fields of an elderly Cherokee man thirty miles away from his owners. Although Michael “grabbed a knife to defend himself,” he was seized and returned to the missionaries, who “thanked the good man and promised to repay him for his troubles.”[2] This story of one boy’s bravery is complex and fleeting like most accounts of fugitivity in the antebellum era. Cherokees helped him as well as hurt him in a place where Native Americans also held Blacks as chattel. Nevertheless, Michael clearly depended on the aid of many Native people during more than one attempted escape from his white Christian owners. Although the documentary record reveals little about Indigenous participation in the networks that enslaved people accessed to free themselves – stories like Michael’s demonstrate that such activity did occur.

Indeed, Michael was not alone. Bits and pieces of evidence point to other African American individuals, families, and even larger parties who sought and received the assistance of Native people while traveling through and from the South in the hopes of reaching freer territories. Thus far, discoveries of written and oral evidence of such activity predominate in the Midwest and Great Lakes region, as recent research by the historian Roy Finkenbine has underscored. This makes geographic sense, as African Americans seeking to cross the Ohio River and then the Canadian border from various (often water-bound) points were moving through territory still occupied, well known, and to a measurable extent controlled by Native people, particularly Shawnees, Anishinaabeg (Ojibwes, Potawatomis, Odawas), and Iroquois Confederacy populations such as the Tuscaroras and Mohawks.[3]

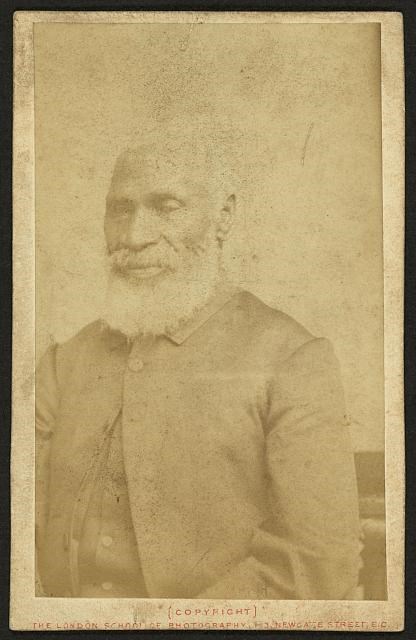

Image Courtesy of the Library of Congress

One of the most dramatic and detailed stories of collaboration in the Great Lakes comes to us from Josiah Henson, whose narrative of enslavement in Kentucky and escape to Upper Canada was a model for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s blockbuster novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Henson recounts the harrowing escape undertaken with his wife and son. The small family was lost, famished, and clinging to an old military road from the War of 1812 as they tried to reach Lake Erie in 1830. Their anxiety escalated when they realized they were being tracked by a group of Native men. Henson reports that instead of attempting to turn back, he and his family asked for help, were taken to a nearby village, fed, welcomed, and given shelter, and then accompanied to the water’s edge the next morning.[4] While Henson does not name the community who likely saved his family and certainly helped to secure their freedom, given their location in northern Ohio, these abettors were likely Shawnee or Cayuga.[5]

Roy Finkenbine has documented other Great Lakes examples based on the records of traders and missionaries living near the Stockbridge reservation of Wisconsin, who, in one instance, describe Stockbridge Indians assisting four Black Missourians on the run.[6] An oral history passed down among community members in the Odawa village of Hungry Hollow in western Michigan describes a community effort to help a group of runaways on the Grand River.[7] The historian Tiffany McKinney has noted the abolitionist politics of free Afro-Native New Englanders such as the Wampanoag sailor, Paul Cuffee, pointing to another region for further exploration of Native American underground railroad activism.[8]

While Michael did not escape long-term from his captors that spring of 1819, a fate he shared with most enslaved people who attempted flight in the Deep South, he did steal time for himself and demonstrate to his owners that he was not pliant “property.” Exactly what Michael did and who he consorted with during the days that he called himself free remains a secret.[9] In Michael’s case, and perhaps in many other cases where Black people entered Indigenous spaces, absence in the archival record might just indicate that a freedom-seeker’s journey was aided by Native agents on the underground railroad.

Footnotes

[1] Rowena McClinton, ed., The Moravian Springplace Mission to the Cherokees, Vol. II, 1814-1821 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), May 1819, 285.

[2] McClinton, Moravian Springplace Mission, May 1819, 285-286.

[3] For a discussion of Blacks, Native Americans, and the underground railroad in Detroit as well as possible Tuscarora activity in the Canadian underground railway, see Tiya Miles, The Dawn of Detroit: A Chronicle of Slavery and Freedom in the City of the Straits (New York: The New Press, 2017), 251-253, 260, 326 footnote 26.

[4] Josiah Henson, The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, As Narrated by Himself (Boston: Arthur D. Phelps, 1849).

[5] Tiya Miles, Michigan Quarterly Review, Special Issue: The Great Lakes: Love Song and Lament (Summer 2011): 434-440, 438.

[6] Roy E. Finkenbine, “The Native Americans Who Assisted the Underground Railroad,” History News Network, September 9, 2019. http://historynewsnetwork.org/article/173041.

[7] Finkenbine, “The Native Americans,” 4. See also Bill Dunlop and Marcia Fountain-Blacklidge, The Indians of Hungry Hollow (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004).

[8] Tiffany M. McKinney, “Race and Federal Recognition in Native New England,” in Tiya Miles and Sharon Holland, eds. Crossing Waters, Crossing Worlds: The African Diaspora in Indian Country (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), 59.

[9] For further discussion of Michael’s life, see Tiya Miles, The House on Diamond Hill: A Cherokee Plantation Story (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 85-86, 159, 161-164, 192, 195, 174-175.