Last updated: February 11, 2023

Article

NAMA Notebook: Benjamin Banneker

NPS

Recently, Ranger Susan and I went on a Black History Month walking tour with a class of fourth graders from a local elementary school. As we stood near the World War II Memorial and looked at the Washington Monument, one of the parents on the trip asked the students which memorials on the National Mall represented Black history. The students thought of the Martin Luther King, Jr., Memorial. Ranger Susan suggested that Black history can be found at all of the monuments and memorials. You just might have to look a little harder to find it. All memorials tell stories, but sometimes those stories are incomplete. One of the teachers commented to me that she liked the way Ranger Susan said that. As we strolled the Mall, we talked about the Tuskegee Airmen at the World War II Memorial and Marian Anderson at the Lincoln Memorial, stories that connect to these places but are not necessarily in plain sight.

This really hit me as I thought about a goal of this series: help teachers find those stories that are harder to see and engage students with National Mall and Memorial Parks.

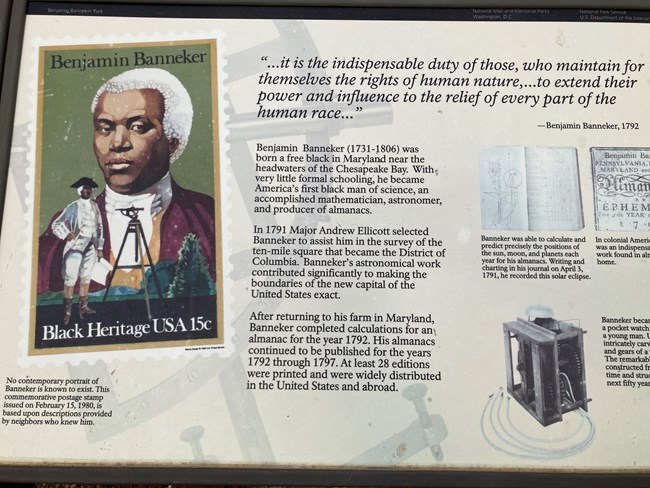

I did a presentation in the summer of 2022 at a teacher professional development session that came as a new story to many who attended. It was the story of Benjamin Banneker, an eighteenth-century free African American scientist who has a number of connections to the National Mall and a number of ties to school curriculum.

Benjamin Banneker

Banneker was a free African American who studied math and science, including astronomy, the science of space. He also built one of the first clocks in the United States in 1753, when he was 22 years old. At the time, Americans mostly told time using sundials and pocket watches. Benjamin Banneker took a pocket watch apart and studied it. Then, he used observations and calculations to design a clock made out of wood. He carved the pieces by hand. The clock was very precise and kept running for more than 40 years. The clock made Banneker famous.

In 1791, surveyor Andrew Ellicott hired Benjamin Banneker to help him figure out the boundaries of what would become the new nation’s capital, Washington, D.C. Banneker spent 3 months at Jones Point in Alexandria, Virginia watching the sky. He kept records of what he saw. Ellicott used his observations to begin placing boundary marker stones around the border of the new city. This trip to Virginia was the farthest Banneker had ever travelled from his home and farm in Baltimore.

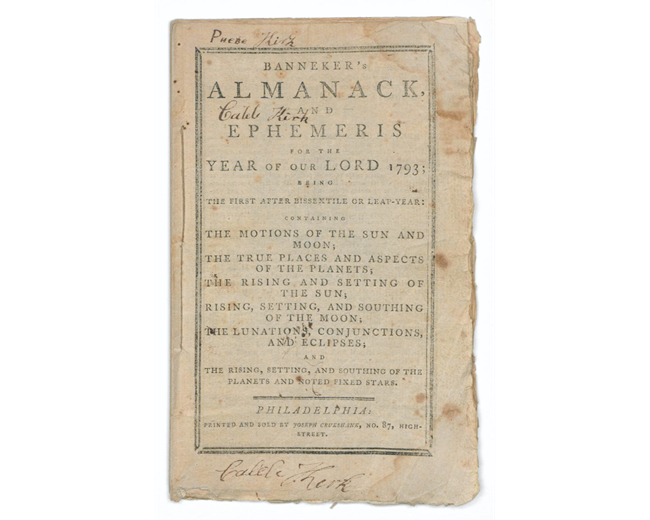

After 3 months, Banneker returned home to take care of his farm and to continue an important project he was working on, an almanac. Almanacs are guides for farmers that predict the weather and give other advice and calculations. Banneker’s almanac also included wise sayings and quotations. Many of the quotes in the almanac countered the ideas many white people had that he couldn’t be a good scientist or mathematician because he was Black.

One of the people who said that Black people were inferior to white people was Thomas Jefferson. In his book, Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson wrote insulting and demeaning things about African Americans. Banneker wanted to prove him wrong. He sent Jefferson a copy of his almanac as evidence, along with a letter asking him to change his mind. He called on Jefferson to be a leader and to end slavery in the United States. Jefferson praised Banneker’s work on the almanac and shared it with a friend, but he never responded to Banneker’s plea to recognize his equality. Banneker published almanacs over the next few years, continuing to share his knowledge with others and demonstrating his math and science abilities.

Banneker lived until 1806. Days after he died, his house burned down. Many of his possessions were lost, including his famous clock. Thankfully, copies of his almanacs survive and stories of his life and work have been passed down through history.

There is a memorial to Benjamin Banneker near the Wharf in Southwest Washington, DC, that is cared for by National Mall and Memorial Parks. If you and your students visit, look up at the sky like Benjamin Banneker. Bring along notebooks and invite students to record what they see.

National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian

Resources

You can view the pages of Benjamin Banneker's 1793 Almanac at the Smithsonian Institution's Digital Volunteers Transcription Center. The Smithsonian invites the public to look at each page and transcribe, or type out, the words. This project is complete, but maybe your class can find another transcription project and participate.

Benjamin Banneker's letter to Thomas Jefferson is available at the National Archives website along with Jefferson's reply.

The Benjamin Banneker Historical Park and Museum in Catonsville, Maryland, is located on the land that Banneker owned. The park includes gardens, trails, and a reconstructed cabin.

NPS Place article about Benjamin Banneker and the Boundary Stones of the District of Columbia

NPS