Last updated: June 13, 2022

Article

Mormon Pioneer Trail Junior Ranger

Interested in becoming a junior ranger?

Use the information below to complete your worksheet!

Once you are done, follow the steps on how to Become a Junior Ranger to submit your worksheet.

The Route West

To the sounds of snapping harness and creaking wagon wheels the pioneers in the vanguard of westward expansion moved out across the North American continent. Between 1840 and 1870, more than 500,000 emigrants went west along the Great Platte River Road from departure points along the Missouri River. This corridor had been used for thousands of years by American Indians and in the mid-1800s became the transportation route for successive waves of European trappers, missionaries, soldiers, teamsters, stage coach drivers, Pony Express riders, and overland emigrants bound for opportunity in the Oregon Territory, Great Basin, and California gold fields.

The trunk of the corridor generally followed the Platte and North Platte rivers for more than 600 miles, then paralleled the Sweetwater River before crossing the Continental Divide at South Pass, Wyo. Beyond South Pass the route divided several times, each branch pioneered by emigrants seeking a better way to various destinations. The route’s importance declined with the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 but continued to receive limited use into the early 1900s.

Timeline of the 1846 and 1847 treks from Nauvoo, Illinois to Utah

Quotations from contemporary diaries and letters describe those years.

February 4, 1846

First wagons leave Nauvoo and cross the Mississippi River.

"The great severity of the weather, and . . . the difficulty of crossing the river during many days of running ice, all combined to delay our departure, though for several days the bridge of ice across the Mississippi greatly facilitated the crossing . . . "

—Brigham Young, February 28, 1846

April 24, 1846

Garden Grove, the halfway point across Iowa, is reached. This was one of several semi-permanent camps set up for the use of later emigrants.

June 14, 1846

Brigham Young arrives at the banks of the Missouri River.

September 1846

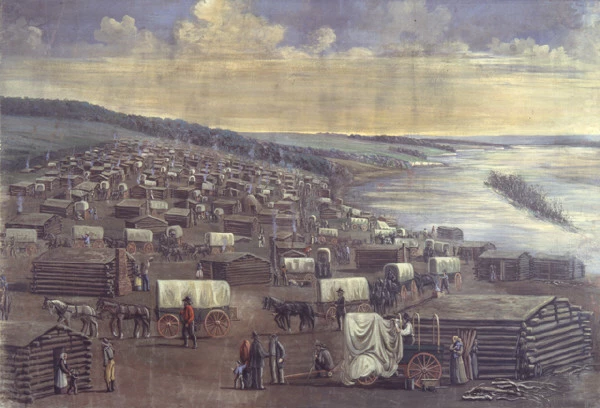

Winter Quarters is set up on the Nebraska shore of the Missouri River. Approximately 4,000 people spent the winter here.

November 1846

Father Pierre de Smet, a Jesuit missionary, visits with the Mormons in Winter Quarters and provides information about the Great Basin area.

April 5, 1847

The first group, led by Brigham Young, leaves Winter Quarters.

"I walked some this afternoon in company with Orson Pratt and suggested to him the idea of fixing a set of wooden cog wheels to the hub of a wagon wheel, in such order as to tell the exact number of miles we travel each day."

—William Clayton, April 19, 1847

May 26, 1847

Emigrants pass Chimney Rock.

"In advance of us, at a great distance can be seen the outlines of mountains, loftier than any we have yet seen . . . their summits . . . covered with snow."

—Horace Whitney Jane, June 23, 1847

June 27, 1847

Mormons cross South Pass, the Continental Divide.

". . . and beholding in a moment such an extensive scenery open before us, we could not refrain from a shout of joy which almost involuntarily escaped from our lips the moment this grand and lovely scenery was within our view."

—Orson Pratt, July 21, 1847

July 24, 1847

Brigham Young arrives in the Valley of the Great Salt Lake.

An Exodus

The Mormon Pioneer Trail

Few years in the Far West were more notable than 1846. That year saw a war start with Mexico, the Donner-Reed party embark on their infamous journey into a frozen world of indescribable horror, and the beginning of the best organized mass migration in American history. The participants of this migration, the Mormons, would establish thriving communities in what was considered by many to be a worthless desert. From 1846 to 1869 more than 70,000 Mormons traveled along an integral part of the road west, the Mormon Pioneer Trail.

The trail started in Nauvoo, Ill., traveled across Iowa, connected with the Great Platte River Road at the Missouri River, and ended near the Great Salt Lake in Utah. Generally following pre-existing routes, the trail carried tens of thousands of Mormon emigrants to a new home and refuge in the Great Basin. From their labors arose the State of Deseret, later to become Utah Territory, and finally the State of Utah.

The Trail Experience

The Mormon pioneers shared similar experiences with others traveling west: the drudgery of walking hundreds of miles, suffocating dust, violent thunderstorms, mud, temperature extremes, bad water, poor forage, sickness, and death. They recorded their experiences in journals, diaries, and letters that have become a part of our national heritage.

The Mormons were a unique part of this migration. Their move to the Valley of the Great Salt Lake was not entirely voluntary; but to maintain a religious and cultural identity it was necessary to find an isolated area where they could permanently settle and practice their religion in peace. This was a movement of an entire people, an entire religion, and an entire culture driven by religious fervor and determination. The Mormon pioneers learned quickly to be well organized. They traveled in semimilitary fashion, grouped into companies of 100s, 50s, and 10s. Discipline, hard work, mutual assistance, and devotional practices were part of their daily routine on the trail. Knowing others would follow, they improved the trail and built support facilities. Businesses, such as ferries, were established to help finance the movement. They did not hire professional guides. Instead, they followed existing trails, used maps and accounts of early explorers, and gathered information from travelers and frontiersmen they met along the way. An early odometer was designed and built to record their mileage while traveling on the trail. In the end, strong group unity and organization made the Mormon movement more orderly and efficient than other emigrants traveling to Oregon and California.

The Ones Who Walked

The Handcarts: 1856 to 1860

A unique feature of the Mormon migration was their use of handcarts. Handcarts, two-wheeled carts that were pulled by emigrants, instead of draft animals, were sometimes used as an alternate means of transportation from 1856 to 1860. They were seen as a faster, easier, and cheaper way to bring European converts to Salt Lake City. Almost 3,000 Mormons, with 653 carts and 50 supply wagons, traveling in 10 different companies, made the trip over the trail to Salt Lake City. While not the first to use handcarts, they were the only group to use them extensively.

The handcarts were modeled after carts used by street sweepers and were made almost entirely of wood. They were generally six to seven feet long, wide enough to span a narrow wagon track, and could be alternately pushed or pulled. The small boxes affixed to the carts were three to four feet long and eight inches high. They could carry about 500 pounds, most of this weight consisting of trail provisions and a few personal possessions.

All but two of the handcart companies completed the journey with few problems. The fourth and fifth companies, known as the Martin and Willie companies, left Winter Quarters in August 1856. This was very late to begin the trip across the plains. They encountered severe winter weather west of present-day Casper, Wyo., and hundreds died from exposure and famine before rescue parties could reach them. While these incidents were a rarity, they illustrate that the departure date from the trailhead was crucial to a successful journey.

Paintings of the Trail

By C. C. A. Christensen - Brigham Young University Museum of Art, Public Domain

C. C. A. Christensen / Public domain