Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Materials Matters (Keynote of the Mid-Century Modern Structures Symposium)

National Park Service

Introduction

Gunny Harboe: Well, good morning.

I too would like to thank all the organizers of the conference The National Park Service, NCPTT, friends of NCPTT, AIA St. Louis, Washington University and the World Monuments Fund.

In particular Kirk Cordell and Frank Sanchis who asked me to give this keynote this morning.

It's truly an honor.

Well I've given lots of talks about my work before over the last 25 years.

Giving a keynote is a little different kind of an assignment and one that I've found a bit daunting. There are many of you sitting out there in the audience today who I've known for a very long time and there's some of you that will also be presenters.

There are also many of you I've never had the pleasure of meeting but I know that amongst you there are literally a millennia of years of experience and knowledge that I could only dream about having.

Yet, I've learned a few things myself over the past three decades since my days as a graduate student at Columbia, New York.

There's only one thing I do know for certain, there's truth in the adage the more you know, the more you know you need to know.

It's a seemingly endless task which is why gatherings like this are so great.

Perhaps nothing I will say to you today is news but I'd like to take this opportunity to remind us all of a few things that I think we should all be keeping in mind as we get on with the important work at hand which is preserving mid-century modern heritage.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Material Matters

Material matters. The title can obviously be interpreted in a number of ways and that's intentional.

It's all relevant to what we do which is why I picked it.

Material matters, that is matters pertaining to materials or material matters.

Materials are really important. In this case it should be seen as a both and proposition.

As professionals engaged in conservation of our cultural heritage we're all dealing with the actual physical stuff.

The issue of materiality is central to what we do.

Whether we are dealing with an individual iconic building, historic landscapes, urban ensembles, fast food restaurants, industrial heritage sites or monumental civil works, we are all charged with preserving and protecting our collective cultural heritage.

The real stuff of the past that is still with us in the present and that we would like to keep for the future.

National Park Service

Secretary of the Interior’s Standards

To guide us in dealing with these issues we've come to use The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties. These are rules of engagement for any interventions required of a historic site.

The standards were first created by the National Parks Service in the late 1970s and they are tried and true. In over 25 years of experience I've found that they work very well in most cases.

This is not to say that they've not had a few times when we didn't fully agree with the SHPO or the park service on some particular item.

But, for the most part, they work very well when it comes to guidance and the proper treatment of the physical fabric of a historic site or what we think of as our tangible heritage.

In the United States the idea of intangible heritage hasn't really entered directly into the mindset of what we do very much but I think it continues to make itself more present.

There is an acknowledgement of it through the evaluation process of a site and trying to understand the significance of something through all of its associative values.

A values based approach to conservation is definitely the way things are going. We've tried to embrace this more and more at Harboe Architects but I don't see it or hear it articulated all that directly in the practice of preservation professionals as a whole. Certainly not in the way it is discussed in some other countries.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Intangible Heritage

I think it is very interesting that there are over 160 signatories to UNESCO's convention of the safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage and the United States is not one of them. Nor are the Australians which is also surprising.

I am sure there are some technical legal reasons why we are not a part of it but it seems a little bit odd that we aren't.

What about our Mardi Gras in New Orleans?

Or gospel singing?

Or the Delta Blues?

Aren't those things worth celebrating and protecting?

Food is something, sometimes a big part of it too.

What about Texas barbecue or California viticulture?

And don't forget the Big Mac.

I only bring it up because I think this idea of intangible heritage is becoming more and more associated with tangible heritage and that it will affect the way that we deal with modern sites particularly in the future.

I'm not exactly sure how but I'm pretty sure that it will.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Intangible Heritage & Our Present

Intangible heritage is much more connected to our present.

It's about cultural traditions or practices that not only have a rich past but that are still practiced today in the present and that may be threatened.

Buildings are certainly aspects of them or could certainly be looked at that way too. I think in some ways we already do this but it is not always clearly articulated in that way.

It's certainly evident in the case of something like the World Heritage tentative list nomination for civil rights movement sites. It includes three churches in Montgomery and Birmingham, Alabama.

I mean no disrespect but these churches clearly are not universally significant for their architectural merits.

They are important because of the events that occurred and the overall civil rights movement that they are connected to.

That could certainly been demonstrated as having outstanding universal value and yet it is the physical site, the bricks and mortar, and in the case of Bethel Baptist maybe a bit too much mortar, we are as preservation professional having to concern ourselves with.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Authenticity

When we are talking about materiality of a building or a site what are we really concerned with? I know it seems self evident but we need to be very cognizant of what we mean by it and what is important about it.

Does it center on the whole concept of authenticity?

When I mentioned that word to colleagues sometimes they roll their eyes. Yes, it seems like authenticity has been discussed ad nauseam, but it is still central to what we do.

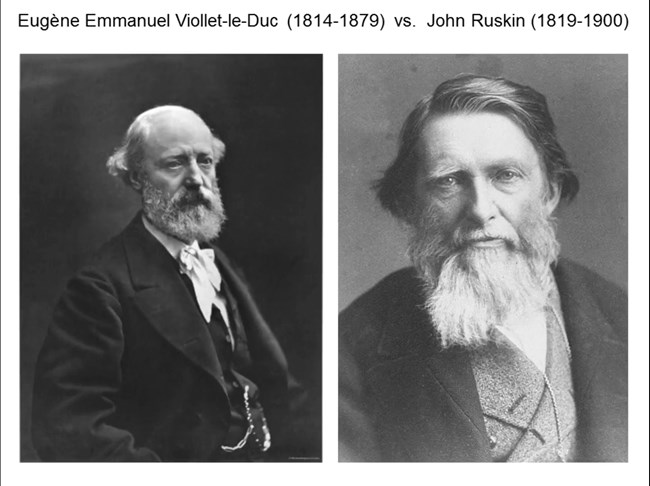

It is unavoidable and has been that way since the discussion about how to treat historic fabric started in earnest in the late 19th century or in the mid to late 19th century with Eugene Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc and John Ruskin.

The so-called scrape versus antiscrape debate.

Other theories and attitudes concerning how to deal with physical fabric of our heritage were further developed by a number of people in the 20th century such as Alois Riegl, Paul Philippot and perhaps most importantly Cesare Brandi.

Their theories and concepts underlie the western attitude about material authenticity that is embedded in the critical documents such as the Venice Charter of 1964 which in turn influenced our own standards.

The publication by the Getty Conservation Institute of many of these texts has been extremely helpful in allowing us to understand how we got to where we are today.

This was of course tempered by the Nara Document on Authenticity of 1994 (PDF, 134kb) which challenged the dominant western notions and laid claim to the importance of understanding what authenticity means in the cultural context within which the object or site was created.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Intangible Values, Tangible Results

It encompassed a broader view of values which include intangible values particularly as they apply to the building arts and what the relationship is between the physical material of the building and the making of it.

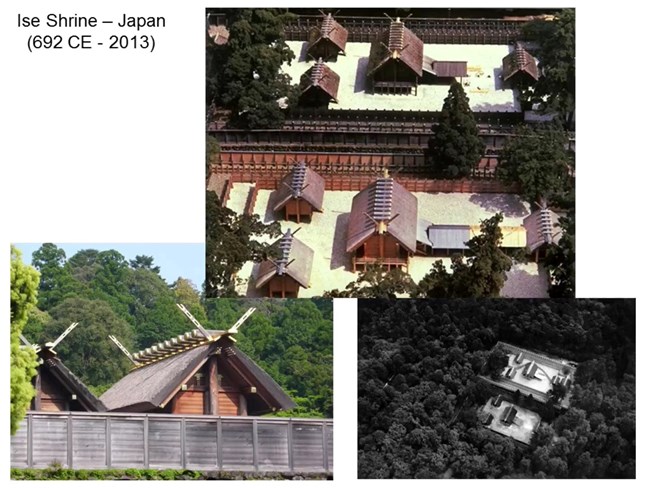

The classic case often referred to is at Ise Shrine in Japan which is literally rebuilt every 20 years.

The physical building is important but not in the way that we typically think of such a thing.

It is really about the process of building or rebuilding the building that is of primary importance.

It is part of the Shinto religious ritual related to death and renewal and is intended to appear forever new. The current building is supposedly the 62nd rendition of the shrine.

The craftsmanship and traditions related to the building act including the craftsmen themselves are part of what is deemed to be authentic. Those things are really intangible heritage but with a tangible result.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Modern Architecture & Traditional Architecture

How does that thinking and attitude affect the way we deal with modern architecture which in some cases means buildings that are less than 50 years old? Should it change how we think about that issue?

In the international arena as well as here in the US there continues to be some discussion about the idea that somehow modern architecture should be thought of as being different than traditional architecture. The rules should somehow change, but I don't really buy that. While there are clearly differences between a really old structure versus one that's only as old as some of us I think that they have much more in common than not. In our practice the process is more or less always the same.

First you have to understand what you're dealing with, what is it about the site that's important, why is it significant, what is it's physical and cultural history? How is it being used now, how will it be used in the future? What are it's deficiencies from a functional standpoint? Are there building code issues that must be addressed and may have a negative impact? Are there acute problems that put the public at risk? What are the patterns of deterioration?

How can it be fixed with the least amount of intervention so that the original artifact can read as truly as possible?

Use the gentlest means necessary, isn't that always the goal?

But, there are of course many other questions that we all ask when we're engaging in a site of historic importance. Not least of which is what the owner wants to know, how much is it going to cost? Figuring all of that out is really one of the most fun aspects of our job, at least for me it is.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Disposable Architecture

Having said that there are some factors that making dealing with modern architecture more problematic than traditional architecture.

For one thing many post war buildings were not necessarily built to last. There was an urgency to get things done, even if you weren't counting on it lasting very long.

There was an attitude of, “Get it up and start using it.” “Use it up, build a new one.” Disposable architecture, just as everything we were consuming in those days seemed to be made to be disposable.

Much of it related to the way we finance things particularly the large sums of money that had to be borrowed in order to get a building built. Once it had been amortized over 30 years it was expendable.

Now, we have a new mantra of sustainability. Everything should be sustainable.

It is clear that our past attitude of use it up and move on is not going to work. The threat of the havoc climate change will wreak it is critical that we pay attention to not just in our work as preservationists but in everything that we do.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Sustainability

But “What does sustainability really mean?” is an actually very complicated question that must be addressed on a project by project basis.

Is it really sustainable to replace all the windows in a building where they continue to retain service life just because they're not as energy efficient as a new one might be?

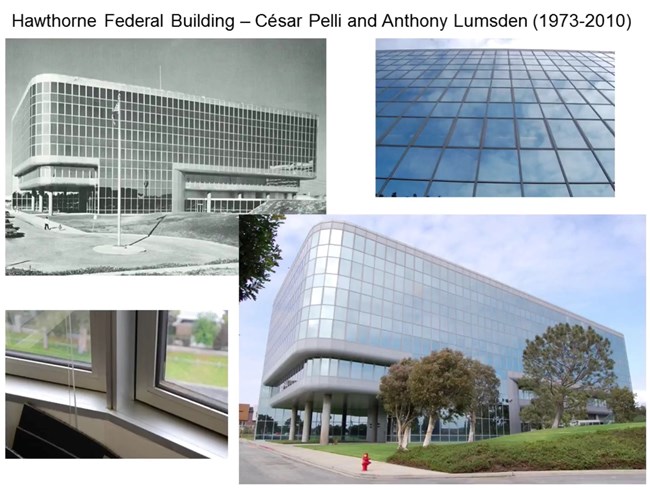

The desire for better energy efficiency is what started the discussion about the 1973 Hawthorne Federal Building in California that you see here, designed by Cesar Pelli and Anthony Lumsden, which was only about 35 years old when this conversation began and GSA decided to do a study.

To their credit GSA and the National Park Service concurred with the determination that this building was of outstanding or exceptional significance under Criterion G. I believe it is now on the National Register. As far as I know the proposed window replacement program has been put aside at least for now.

The battle of whether to replace windows or not especially with large buildings we're speaking about whole curtain wall systems. This will continue to be a major issue. Understanding the value of the embodied energy in existing building fabric is certainly a step forward and has helped to level the playing field to some degree.

But LEED the Leadership and Energy in Environmental Design still really only looks at buildings in a quantitative way. What about the cultural value of the building? Yes, you can replace the curtain wall and you might save some energy, it might even make economic sense but what have you lost?

What is the true value of our cultural heritage and it's material authenticity. If we want to be truly sustainable as a society and a culture we have to include those issues in the discussion in a really meaningful way and I don't think we're there yet.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

With our aging building stock the question of how to treat high rise construction is going to continue to be a huge issue. In many cases it isn't just a question of wanting to improve performance. In some cases the existing system is failing.

Modern architecture was by its very nature experimental, its architects were inventing new ideas about architecture, it's form and function as well as pushing the building industry to develop new technologies and how it could be built as we just heard.

This only intensified over the second half of the 20th century as completely new ways of making buildings became standardized and economic models of planned obsolescence became more common.

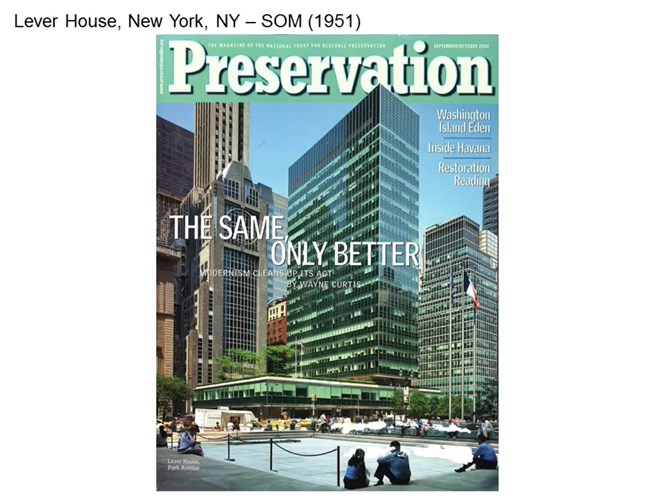

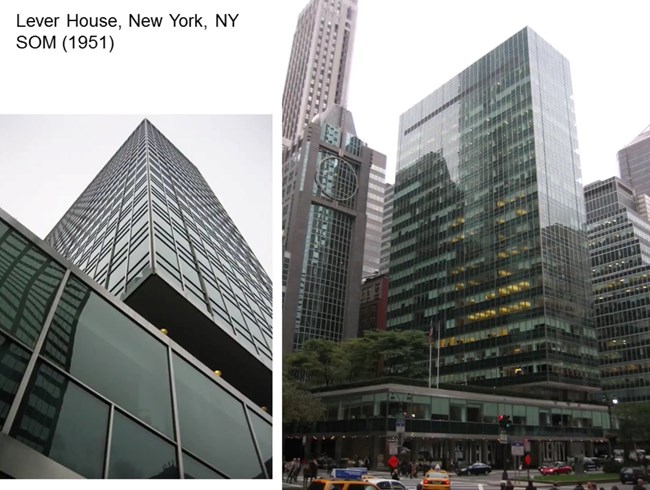

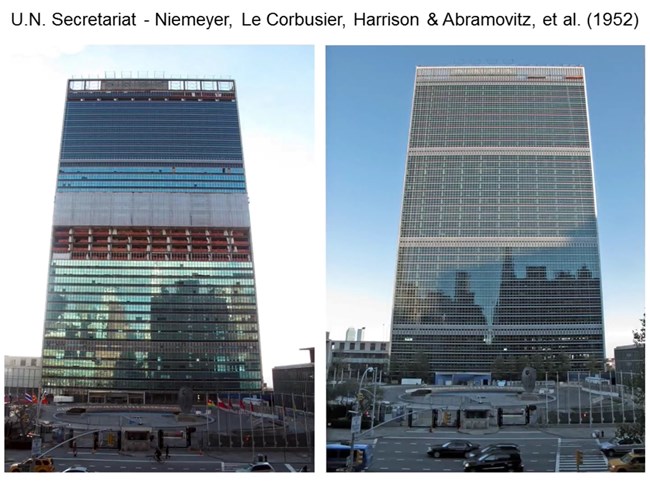

What can you do when the fundamental problem is not really fixable without a complete dis-assembly? This was the case at SOMs Lever House in 1952 and with the United Nations Secretariat building by Oscar Niemeyer, Le Corbusier, Harrison and Abramowitz among others both located in New York City.

Lever House is certainly one of the most important post war skyscrapers anywhere. It's significance is clear, it was made a New York City landmark in 1982 and listed on the National Register in 1983 just over 30 years old not 50.

But the structural support of the curtain wall was deteriorating from the inside. The only option was replacement which they completed in 2001 and from what I understand of the project I think they did a great job. They saved the building and they were able to be true to the original detailing as closely as possible while using a modern system.

The results look great but did we lose something?

It's a very similar story with the UN Secretariat Building. This too had systematic problems with the curtain wall that went way back to when it was originally built and value engineered.

They had an additional challenge here that they had to meet new security requirements for blast resistance. There was little choice but for complete replacement while trying to aesthetically match what was there originally as closely as possible.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Did architects care about longevity of buildings?

These kinds of fundamental or systematic problems begs the question, “Did the great architects of the mid-century care about such things?” Did Mies, or Frank Lloyd Wright, or Le Corbusier or Alvar Alto or Lou Kahn, or Eero Saarinen did any of them really care what their buildings would look like after 50 or 100 years?

It's not really clear at least not in the readings I've done.

I do remember hearing once that Phillip Johnson said he didn't care what happened to his buildings but I couldn't find the quote.

He evidently cared enough about his own home to leave it to the National Trust with an endowment so that we could all enjoy it and I think that we're much richer for that that's for sure.

I would be interested to know if that statement I just made if any of you in all the research that's has been done, in hundreds and hundreds of hours out there.

If you know of such occasion where you have the architect on record of doing this or that because they know that they want it to be something to be around I'd be very curious to know.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Preservation in Perpetuity?

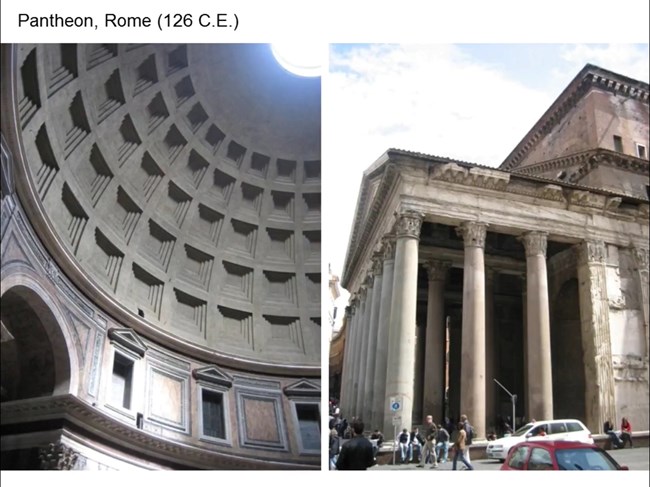

The Romans, they were building for the ages and in some cases their building have lasted an amazingly long time such as the Pantheon in Rome which is probably my favorite building anywhere in the world.

But is this to be our standard?

How could that be possible?

When we landmark something there's actually an implied intention that this thing be protected in perpetuity.

What does that really mean to preserve something in perpetuity?

Forever is a very long time, is that sustainable? Probably not.

What about all those new buildings being designed and built today by the world's architects?

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

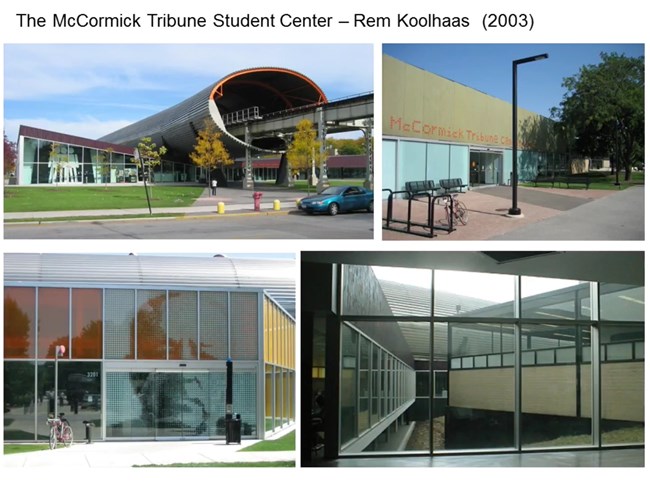

Do you really think that buildings built by Zaha Hadid or Rem Koolhaas are sustainable?

Do you think that some of them will be landmarks someday?

Yes, some of them certainly will be but what happens when the fiberglass egg crate panels at the McCormick Student Center at IIT built in 2003 become so discolored and frayed that they need to be replaced?

I don't how well you can see it but this thing is totally furry because of the UV-degradation. As you can see it's reached that point already. And when the university finally gets around to fixing it, which they're not intending to do any time soon, as I know for a fact, will you still be able to find this material? And if not, how will you have it remade so that it matches?

It's just a problem waiting and the orange plastic as well that's not the photograph that's just the fading of the material as well as the black paint you see at the top here which is …

This isn't actually the worst location, there's many other places where it's completely discolored and getting in the way of what the original design intent was to understand the building and it's only 12 years old.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

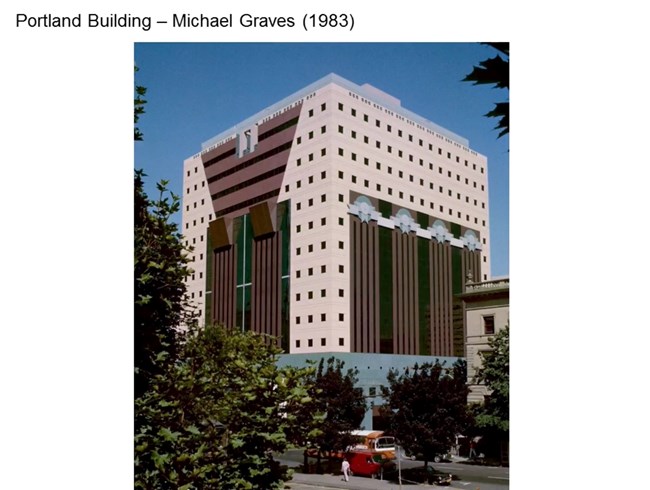

In another example the Portland Building by Michael Graves, who we just recently lost unfortunately, in Portland, Oregon. It's a great post modern pile. It has been made a city landmark and rightly so in my opinion.

But this building has lots of problems, it was value engineered when it was originally constructed and it has not weathered well. What are they going to do with this?

The latest technology that will greatly have … I think will greatly have an impact on what we do or certainly on architecture is 3D printing.

I just read an article a few days ago in Art Record where there's a group of architects in The Netherlands that are building an entire house out of plastic using 3D printing.

There are also experiments going on using 3D printing with concrete materials to make actual buildings. What does that mean for us, how durable will these things be? What will this mean for the next generation of heritage practitioners?

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

What to Save, What to Let Go

How do we decide what to save and what to let go?

I just heard about this book recently published called Buildings Must Die, A Perverse View of Architecture by Stephen Cairns and Jane Jacobs.

Has anybody here read it? Have you ever heard of it? I just heard about it about a week ago and I haven't had the chance to read it but I did about the reviews and so on.

The premise is an interesting one, must buildings die? Are we willing to accept that? Much like a doctor who has a terminally ill patient there are times when it becomes clear that the patient or in this case a building cannot be saved at least not in its current form. It doesn't stop us from trying but we need to know the limits of what is possible. In many cases the deciding factor is money.

Preserving an existing historic structure takes money and if it has been allowed to deteriorate significantly which they usually have been it takes a lot of money. Sometimes more money than can possibly be raised for the occasion.

In any event often there's not enough to at least do what needs to be done in an appropriate fashion.

This is not a new situation, it's what gave rise to the Federal Historic Tax Credit Program administered by the National Park Service.

The 20% HTCs have been hugely successful in saving thousands of buildings and giving them a new life.

According to the NPS website it has leveraged $69 billion in private investment to preserve over 39,000 historic properties since 1976. That is an amazing statistic.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

[Image links to TPS Tax Incentives]

Advocacy

But everyone in this room should know that the HTCs are often under attack from Congress and in fact right now as we are sitting in this room it is currently being considered whether to be re-supported by the Senate Finance Committee that's what this letter is about.

I encourage all of you to make sure that your representatives in Congress know the importance of this financial incentive to communities.

It's not just about our profession although it is important to our profession but it's really important to communities both culturally and economically.

How many of you in the audience are members of Preservation Action or the National Trust? Raise them high, okay, that's not even half.

I'm sorry but you should be embarrassed, you should be, you should all be members of one of those organizations.

I mean if you can't advocate for what your professional involvement, your life blood is about, who's going to do it? You really need to do that. I'm not done with my public service announcements yet.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Timeline of Brevity and Loss

As the timeline we're all on moves forward everything feels sped-up and the durations get shorter and shorter.

I don't know if it is just because I'm getting old or it's because the internet or because the seemingly endless need for instantaneous everything that we seem to have as a society. But everything's going faster and faster.

The earth still only rotates once every 24 hours but the perceptions of the world can change overnight.

Whatever the cause the result and that reality is affecting us and how we think about our cultural heritage more and more.

As I said, post modern buildings are beginning to be recognized as landmark worthy. Does the Park Services' so called 50 year rule does that need to become, the 25 year rule or should there be any limit at all?

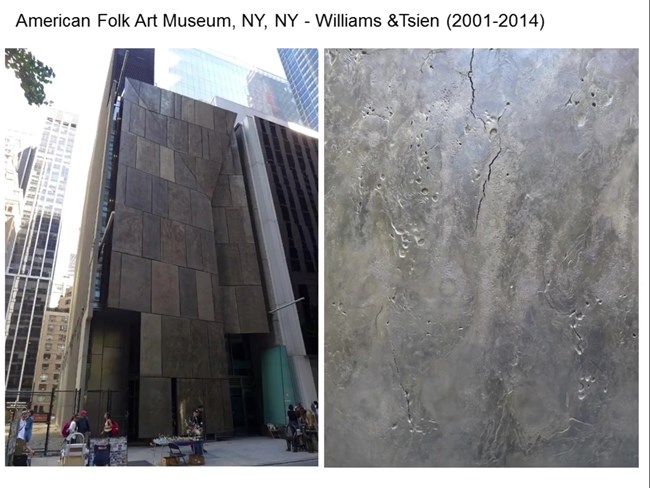

How much time is enough time to make a judgment about a significantly great work of architecture. I'm sure you all heard about the uproar over the demolition of the American Folk Art Museum which was designed by Todd Williams and Billie Tsien and completed just in 2001.

It was a beautiful building and it didn't even last 15 years.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

[Images links to information about the Cyclorama Painting at Gettysburg.]

We also have to deal with the sheer quantities of built stuff.

There's so much building stock from the post World War II boom that it boggles the mind. Obviously all of it is not worthy of protection but making good choices is not always that easy.

We still seem to be applying the same criteria we've been using for the last 50 years and I think that's appropriate, it seems to work generally. There's a good understanding of what the criteria are and whether something meets them or not.

Yet the system doesn't always work. We've had some major losses of mid century modern buildings in the last few years that are baffling at least to me.

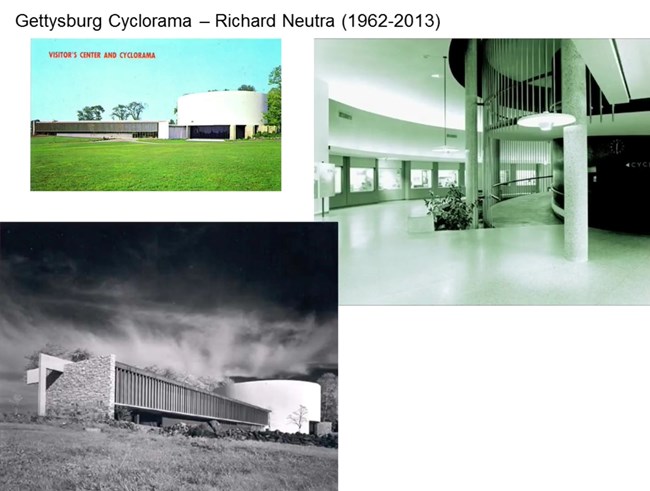

The protracted fight over Richard Neutra's visitors center at Gettysburg National Military Park otherwise known as the Gettysburg Cyclorama of 1962 ended with the demolition of a structure that clearly met a number of criteria.

I am sorry I don't mean to be insulting to my hosts but I think they got that wrong and it was a huge … There were good arguments on both sides and in the end the people that believe that the landscape was more important to show that part of the battlefield won out.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

But we clearly lost something, we lost many important lessons, history lessons, story lessons, even sometimes mistakes need to be embraced and interpreted and explained why things are the way they are once you erase it that's gone and it's much more difficult to tell that story. I'm sorry this is during …

My own home town of Chicago, you don’t get off the hook either.

We had a huge fight over Bertrand Goldberg’s Prentice Women’s Hospital.

It’s a poetic and precedent setting building, built in 1975.

It met four out of the five criteria the city uses for landmarking.

We had to fight just to get them to acknowledge that.

But in the end they did, they agreed, “Yes, it’s landmark worthy.”

They voted to land mark it and then five minutes later in the same meeting they voted to delist it and tore down the building, let Northwestern build a new building.

What kind of a precedent does that set?

For us in Chicago that’s a very scary new reality.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

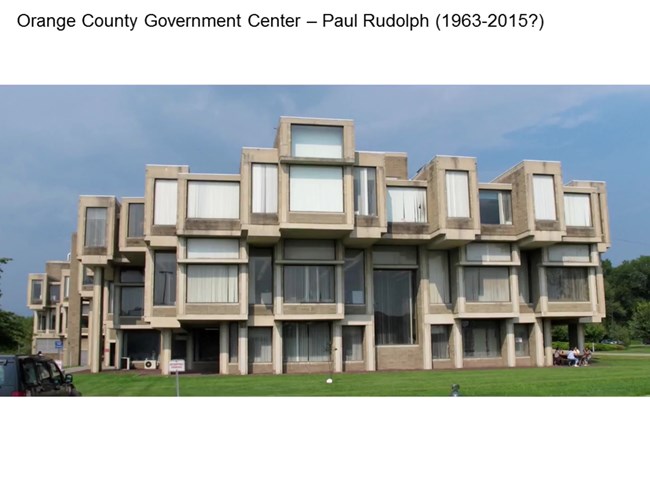

For this example what's going on right now in New York, in Orange County, Paul Rudolph's Orange County Government Center in Goshong built in 1967.

This has been on the World Monument Fund's watch list since 2012. It appears to have been handed a death sentence by the county and is headed for the landfill, that will be useful won't it, despite a seemingly reasonable alternative to buy and reuse it.

Although a few days ago it got a reprieve, a judge issued an injunction or a stay to keep it at least until July and the direction in the letter which I read was pretty clear that he wants someone to figure out a way to save it but there's no guarantee.

There are of course many other examples and whatever your opinion is about the way these buildings look they all demonstrate multiple cultural heritage values at least enough that would make them more than meet the threshold of landmark status by the standards we typically apply.

They are all losses, all in the name of progress. What will take their place?

If we're going to lose something as meaningful and has a purpose that these things had it shouldn't be in vain. We need to be demanding more out of new architecture.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Cultural Values and the Built Environment

What is the problem?

Why are we losing these things?

Who should decide what stays and what goes, what factors play into it?

Is it only about the money? Money that owners think they can make it they maximize the development of the site, money that isn't making itself available to rehabilitation or restoration.

It is just left to sit and fall apart until demolition becomes a matter of public safety?

What do we value as a society, what's important to us?

These questions also change and shift with time although there are many more people now who are interested in modern heritage today as evidenced by this turn out of this group and what we've already heard this morning.

There are still many people who don't get it or don't care or who are downright hostile towards it. These are the kinds of battles that organizations like Docomomo have been fighting for a very long time.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

[Image links to Facebook Page for ICOMOS' 20th Century Heritage.]

Who here has never heard of Docomomo? How many of you are members of Docomomo?

Even less than Preservation Action or the National Trust.

Again, I'm sorry but shame on you.

If you can't support organizations that support you you've got a problem.

This is the 20th anniversary not just of Preserving the Recent Past Conference but that conference is what gave birth to Docomomo US in 1995.

We are celebrating the 20th anniversary and I think in honor of that at the break you should all take out your smart phones, turn them back on and after you check your email go to docomomos.org and join, it's not that much money and this organization could really use your support and you need the organization or at least I think you do.

They are also having another conference, their annual conference will be up in Minnesota in June so you can check that out when you're on the website becoming a member.

Another group that I'm quite involved with that you should know about or maybe you do know about it but it's not as well known as Docomomo is the International Scientific Committee on 20th Century Heritage, they have a lot of acronyms that I could almost … Thank god, our is the ISC20C.

We've been fighting to protect important 20th century cultural heritage all over the world, not just modern heritage although that falls in our purview but all heritage of the 20th century.

If you think things are bad in the US trying to fight for modern heritage it's even more difficult in other places in the world. To that end there are a couple of programs we've created to help the cause on the international level.

Madrid Document: Approaches for the Conservation of 20th Century Architectural Heritage

In 2011 we published something known as the Madrid Document orApproaches for the Conservation of 20th Century Architectural Heritage.

It has been very well received in countries that do not have a well-developed methodology or guidelines of approaching modern heritage like we have with our standards. It has now been translated into 12 different languages including Finnish, Hindi and Mandarin Chinese.

We are also very active with advocacy through our Heritage Alert Program which has been used to effectively save a number of threatened structures in places like Stockholm, Hong Kong and Mexico.

I encourage you all to check out their website as well, this is the Facebook page which is actually a little more current than our website. To join US Icomos which is the branch of Icomos here in the states and if you want to know more specifically about the IC20C I'd be happy to … You're welcome to contact me and I'd be happy to tell you more specifically about that.

Okay enough of the public service announcements.

I am just trying to make a point here that many of you already know that dealing with this modern, mid-century modern heritage is pretty much the same as dealing with traditional architecture but in some ways more difficult.

There are so many factors at play that there's almost never a perfect solution. It always involves making informed choices and developing reasoned compromises.

If very you're careful and include attention to detail you can usually come up with a good solution that not only retains the heritage values of the building but gives it a continued use of value and economic value for at least another generation or two.

Okay, well you're not … Don't be so sure.

Now I am getting to the case studies.

I normally don't read these things out, my apologies on that but when it's supposed to be 15 minutes to an hour it's a long time to remember in your head.

Some of you have heard some of these stories before at other venues but I'm going to share them with you anyway because I think the lessons are still worthy of telling.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

As many of you many know I've had the great honor and pleasure of working on a bunch of Mies buildings at IIT and elsewhere. I think I'm up to a dozen now or more in some capacity or other. Not all of them have been full restorations but they've all informed our work.

Mies was an incredibly gifted architect, certainly one of the best we had in the 20th century but his buildings have problems. This goes back to my point earlier about whether or not the great modern architects thought about this or even cared. Less was not always enough.

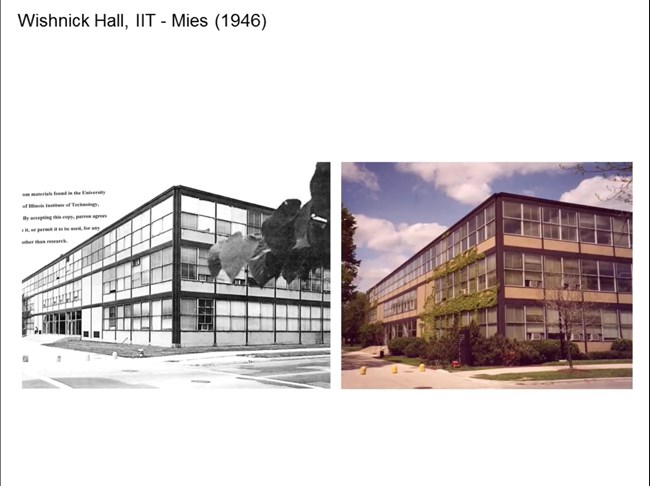

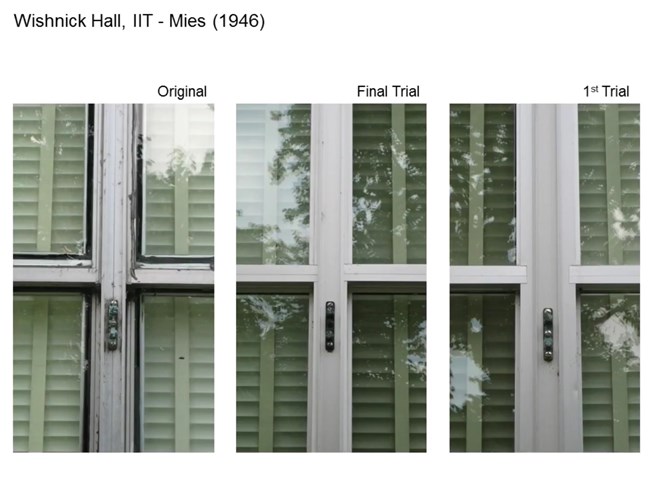

At Wishnick Hall originally completed in 1946.

Holabird & Root in Chicago were asked to renovate the building to accommodate a new state of the art teaching lab. It has always been a teaching lab but it was in need of many upgrades including full MEP, FP systems and of course the question of the windows came up almost immediately.

In this case I was hired by IIT to consult with Holabird & Root about the windows.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

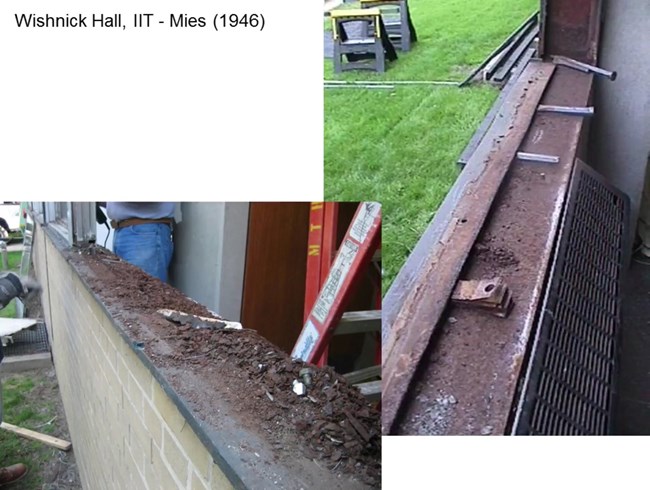

Of course they wanted to find a way to improve their performance but most significantly they had to address the deterioration of the sills which you see here.

The rust-jacking had caused this sill to basically have this roller coast … That's not distortion in the picture that the distortion in the steel.

We had to try to figure out what to do. A window was removed to figure out what was causing all this and that also allowed us to really take a close look at what was going on with the aluminum window.

I think I mentioned, oh it says right there 46, there is a very early building on that campus, one of the first that he built.

When we got it out we could see what the problem was, was this corrosion that had been building up between the steel sill and this steel that went down … The structural member that went down into the masonry wall below.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

The only way to deal with this was to take out every window and clean all this up, put in a new sill and put in a window.

But we weren't really able to reuse the old window because it was actually about falling apart on its own, there was no way to make it more energy efficient and it was very expensive even if we could do it.

Just there were so many things going against it that the decision got made to replace them. With that, that was the reason compromise.

Here you see the comparison with its ten year younger twin building the Siegel Hall which is almost identical to Wishnick Hall but it is ten years younger.

There they changed the detail, I don't how well you see it but there's about at least a half an inch difference between here and here and the heavier sized steel, thicker steel that they used to do that sill detail.

They had almost none of the same problems so they had figured out … I think it already was developing problems within the first ten years so they changed it.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Once that decision was made to replace the windows we still had to work diligently to get as close to the original profiles and site lines as possible which is standard practice I'm sure with you, right?

But it still took several attempts by the manufacturer to get something that was an acceptable match.

It isn't perfect but it's pretty close. Here you see the first trial on the right, the lower right there.

Here you see closer how it didn't match close enough, the one on the left is original, the one on the right is the first attempt.

Here you have the … It's hard to see this it's almost an optical illusion but the one in the middle is the one that was deemed to be close enough to the original profiles to be acceptable.

That's the one that has the new black paint around it.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

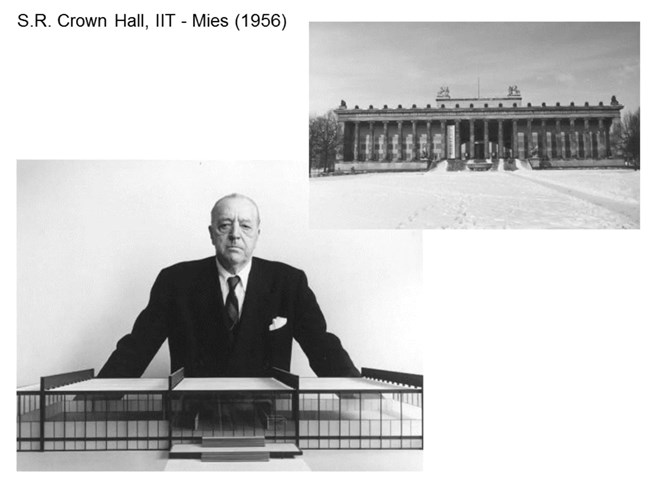

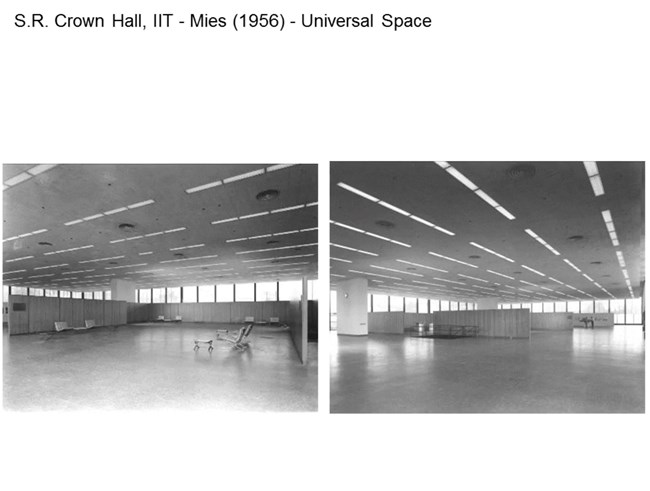

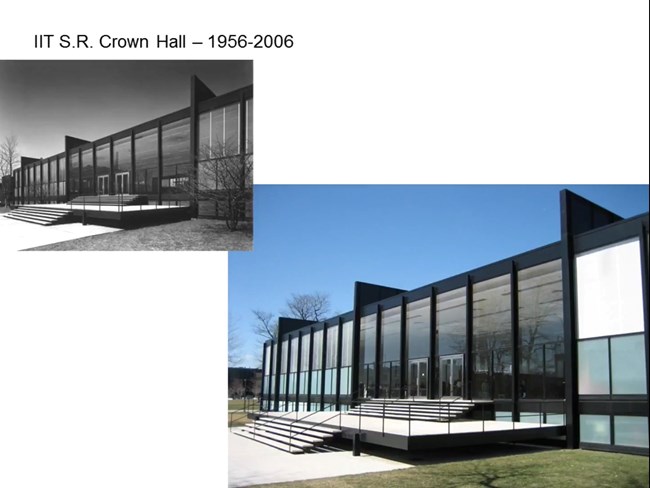

Crown Hall was one of Mies' most important works anywhere.

It was his first physical manifestation of universal space which was a concept he had been working on for a long time.

What he created was a building that was almost an instant icon.

Countless architects make the pilgrimage to see this building every year and it still functions as the home of the School of Architecture.

Crown Hall had a major renovation done by SOM in the late 1970s which included the replacement of virtually all the original glass, not virtually but all the original glass and an installation of a new laminated glass to mimic the original sandblasted glass in the lower lights.

In the intervening years it was not maintained very well, I don't even think it ever got painted.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

The green growies were going wild, the Travertine was falling apart, the one on the lower right that was Donna Robertson's office where the vines were actually growing inside.

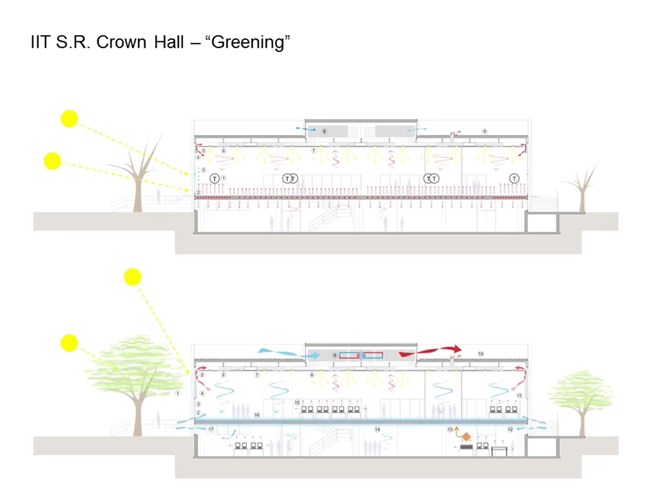

She got tired of it so in 2003 she decided she wanted to restore Crown Hall and to use sustainable practice to do it which was a new thing at the time.

She called it, “The greening of Crown Hall.”

This was a dozen years ago and the sustainability movement was still brand new at least in this country and she hired Krueck & Sexton Architects to be the architects of record.

Both Ron Krueck and Mark Sexton had gone to school there and myself as the restoration architect when I was still with McClier.

And not one but two sustainability consultants Transsolar and Atelier Ten.

They were both European-based firms that were looking for ways to get into the US market and they were great guys to work with and very much the team players.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

They did some greening studies, you see here one of their ideas about how to use the passive qualities of the building that were actually designed in, how to make them work better.

Then there were a lot of studies done about the glazing, how to get better performance out of it.

Of course, the idea of double and maybe even triple glazing came up but we put that off the table rather quickly because of the aesthetic impact it would have on the beautiful simplicity that is Crown Hall.

Once we got them off of that as being too radical an aesthetic change it was determined that going back to the original sandblasted glass would actually have some very positive features about it that would make the building more sustainable, better performance and more sustainable.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

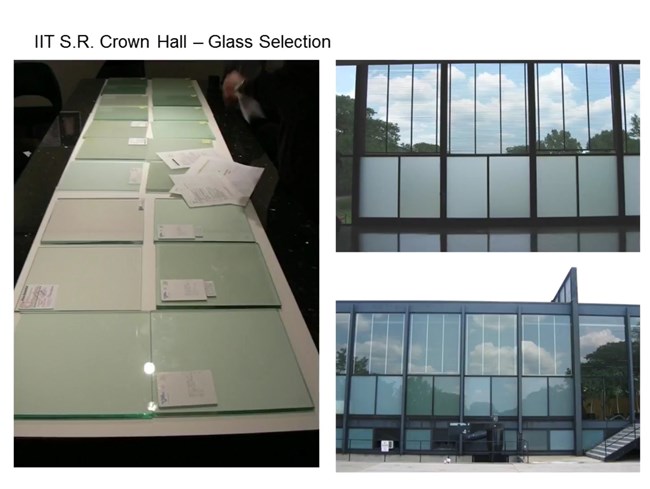

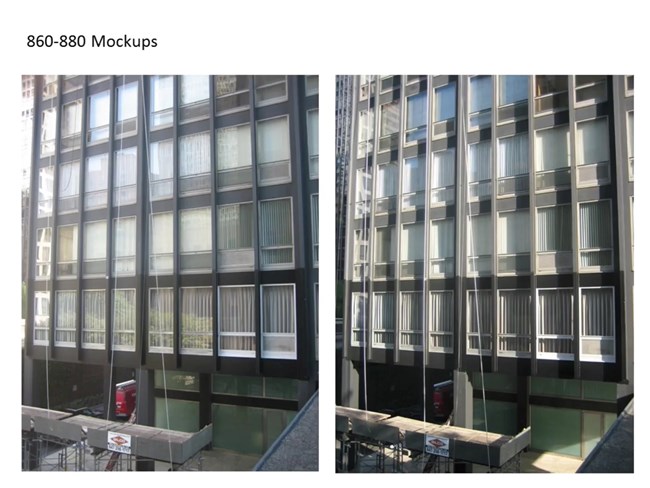

While working with K&S we began to investigate the possible glass options and you can see how many possibilities there are out there and any of you that have tried to match glass today know that there are countless possibilities and this is only a few of them here.

We did at least three times that many sample selection or sample collections.

On the right you see six full sized mock-ups which we felt was really the only way to judge what was or wasn't working.

We included in that some laminated solutions to see if they were really as aesthetically bad as we had anticipated and they were.

The final solution we came up with was going back to the original sandblasted glass but with a clear sealer, a proprietary sealer than no one knows what the magic formula is.

But nonetheless it works to keep the soiling and the abuse that the architecture students are known to do.

They love sticking stuff on this because it's this beautiful soft light that they can trace over. They do still do tracings in architecture school believe it or not or at least to put stuff up on the wall.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

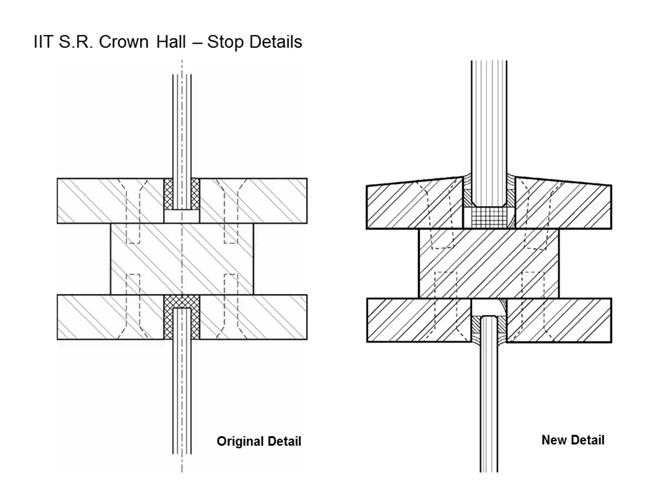

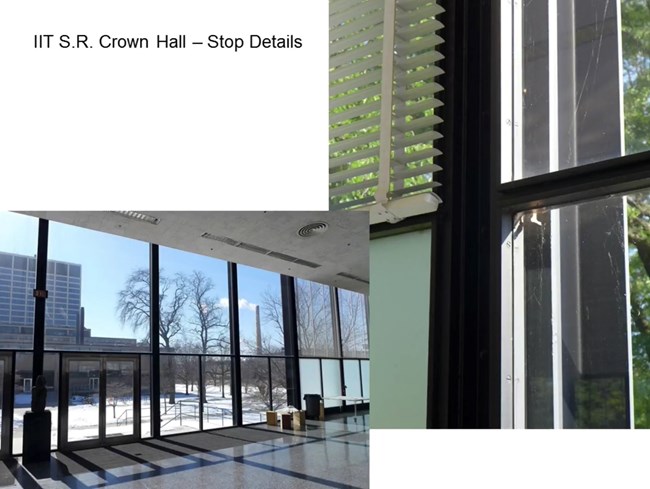

Then the big issue became how to address the need to increase the size of the stock of the large upper lights that were so big that the requirement, the code requirement, was to increase the bite on the glass.

As we all know about Mies, God is in the details.

When you change the details you're messing with God.

This was a big, big deal, we had lots of people working on it and the Mies police as we call them they were out in full force.

We came up with a number of options and tried them all in mock-ups and again at the end of the day the sloped option proved to be true even though there was very vocal opposition to this as being completely unacceptable in a 90 degree Mies world to introduce any kind of a slope of any kind.

I don't know how well you see, it doesn't really matter because you can't see it.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Anyway on the upper right it is the upper stops that have the angle and yes in certain sunlight options you can see that there's a little bit different of sheen or a different way that it reflects the light.

Basically, it's imperceptible especially when the shades are drawn on almost all the upper lights all the time.

But what was important here as well was the daily construction administration observations that either myself or Tim Tracy did from Krueck & Sexton because we only had 15 weeks to complete the construction, this is the time when the school closed to when they opened again.

That was an intense summer and one of the driest summers on record in Chicago which was hugely helpful.

This is Dirk Lohan in the right lower, on the right side with his son, so that's Mies' grandson who is also a very prominent architect in the states in Chicago in particular and his son.

So Mies' grandson and great grandson having the pleasure of breaking the non-original glass, no original glass was harmed in this video.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

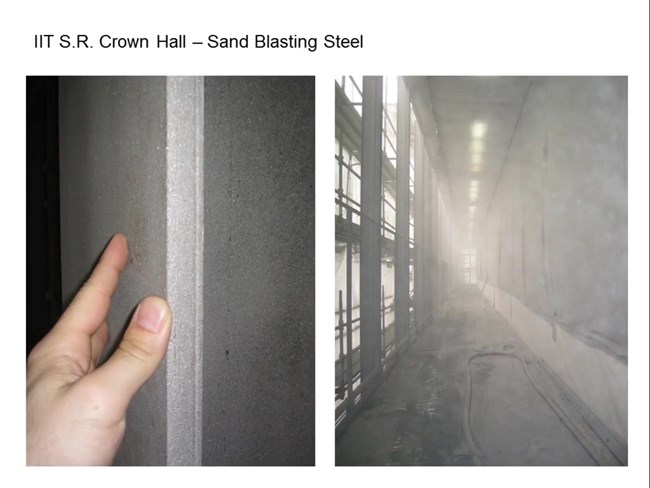

You can see the conditions that we found were horrible, was really way overdue.

We had to wear these suits because of the sandblasting that was required to get down to the steel, of course it was lead based paint.

You had to have a blood test before we started the project and one afterwards to make sure we weren't poisoned.

And this kept all the Mies Police at bay because they didn't go through that testing so they couldn't actually go in and inspect what was going on but we did.

We did on a daily basis, lots of testing in the course of the work. We did institute water tests, etc.

The big day came to put in the glass which needed ten glazes to do it.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

I think … I mean the machine was doing most of the work but the union requires there be ten guys there at all times which is one of the reasons this was expensive.

There was very tolerance between to slide that thing down between the steel to get it into place.

I think the results are beautiful and I think Mies would be pleased not spinning in his grave as some people had thought.

That led to work on 860-880 Lake Shore Drive another Mies iconic structure 1951.

Again it was the same time, Krueck & Sexton were the lead architects, I was the preservation architect and Wiss Janney also joined us providing structural engineering and conservation and forensic consultation.

The buildings did not need re glazing unlike the examples I showed earlier at Lever House and the UN Headquarters.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

The aluminum windows were actually in very good shape.

The real question was whether or not the paint would take another coat of paint because it had already been painted a number of times.

Can you see the original aluminum storefront system which I'll get to in a second which had been reclad with stainless steel in the early 1980s.

Of course the initial thing was onsite investigation, we're up on the scaffolding checking things, looking at things and, of course, the paint is failing basically everywhere.

We knew that full removal would be very very difficult and expensive so Wiss Janney did a bunch of tests to see how the paint was holding up.

And its adhesion. And it was determined that we could get away with painting it at least one more time.

These are all mock-ups and so on.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

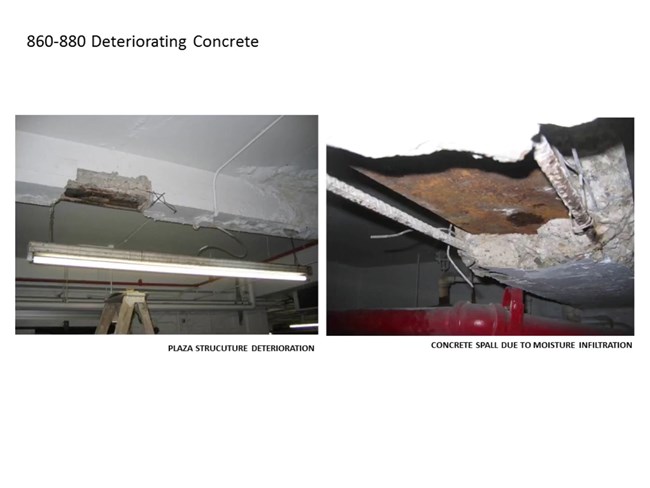

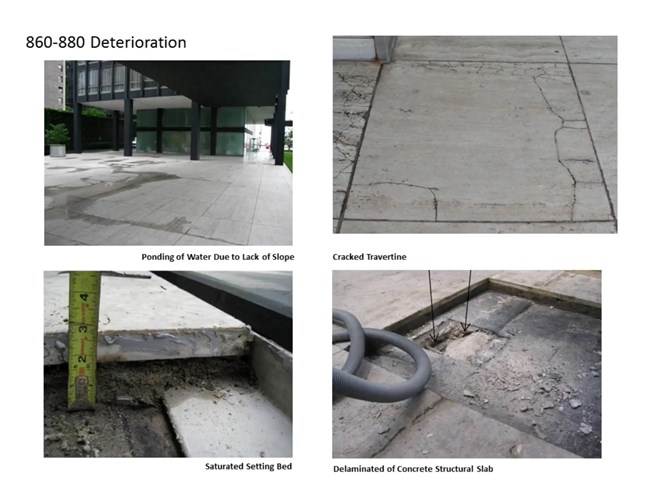

The travertine plaza was another story however, it was failing systemically and had been doing so for many, many years.

The Mies were all again at 90 degree angles, a dead flat plaza with only one solitary drain was not enough.

There have been several campaigns with major renovations, a major renovation in the 80s.

You can see here all the different kinds of repairs that had been made over the years, it was quite patchy and obviously on the right slide you see it wasn't doing it's job.

The biggest problem was really the fact that it was dead flat and it was holding water, you see the puddling water here. Obviously it is not flat there.

But where it's supposed to be there was penetration through the slab and the parking garage that sits underneath the towers was spalling concrete on peoples' Mercedes and things like that.

That's not a good scenario.

They got tired of that and they decided to bite the bullet and invest a number of millions of dollars in repairing this thing.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

The problem with the plaza was really that the original construction tolerance was not enough.

You can see on the lower left there that the setting bed was not deep enough as you would normally want between the top of the slab and even the thinner stone that they've got there.

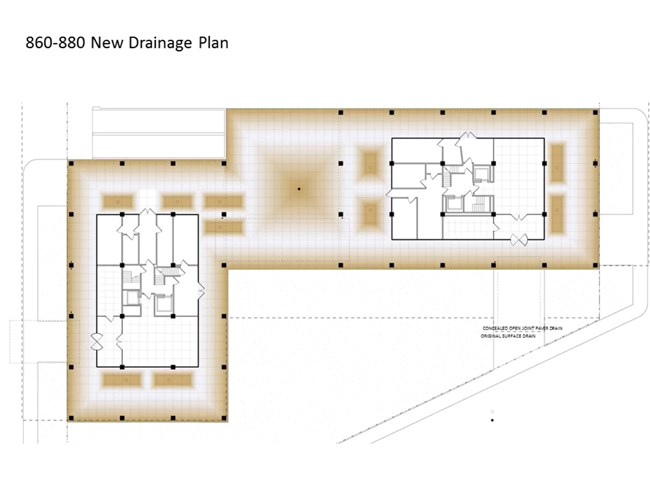

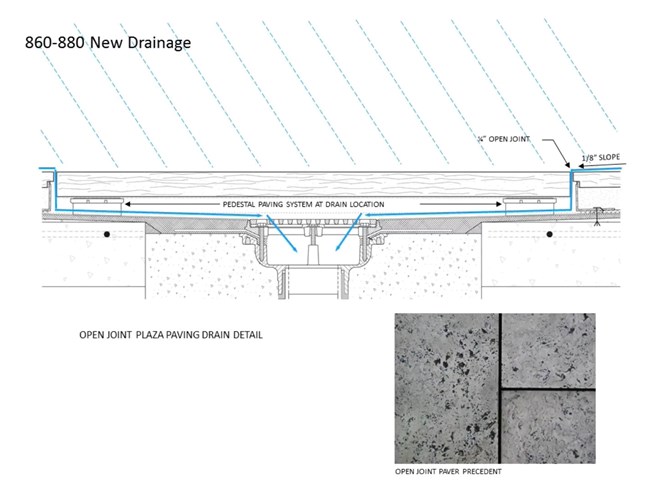

Working together was really actually a very fun project, the whole team got together I think there were like six or seven of us several times having workshops and trying to figure out what to do and the system that was devised was to add a bunch of internal drains, subsurface drains you see them in the darker shaded areas here and then add a little bit of slope and have that one single exposed drain which were still going to use.

Here you see the system, the rains comes down and it goes down the drain.

It is basically like the pedestal system but it is laid into a setting bed system.

It was kind of a hybrid thing and it has been working very well.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

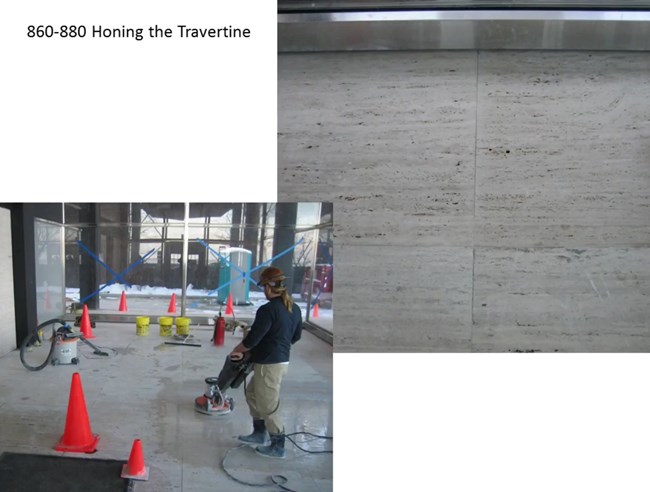

We also had to match the stone which is also a big deal as any of you know that have worked on buildings where you have to do this.

The only way to make sure that you are getting a good match is to go to the source.

Fortunately for us it was in Rome.

And Rico, Cedro, K&S and I made a couple of trips there both to pick the stone and also to observe the shaping of the stone.

Because this required a number of the stones to be honed in a way that allowed a valley or a ridge in order to get the draining to work in that one area that we were looking to have the actual surface drain function.

This is the original storefront as I mentioned, it was aluminum, it was replaced in 81 with a stainless steel system.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

They knew there were problems with galvanic action, they were having problems with the steel, underlying steel, they thought putting this …

I guess they thought putting the stainless on was going to cure the problem but really what the problem was was the fact that the original design didn't taken into account the negative air pressure that a tall building has.

Now of course we have positive pressure pushing air out of the building, then it was just sucking air all the time.

While they were able to address that with sealant on the windows they weren't able to deal with the storefront very well.

And every time it rained it would suck water in to the system and didn't let it bleed out very well.

You see on the lower right the result of the underlying steel.

This gave us an opportunity to cheat a little bit again with the risk of having Mies roll in his grave.

We raised the … Originally those were level, the inside mountsides were dead level.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

But because you can't see it anywhere around the base that base element actually blocks your view for direct view between the two.

We raised it about an inch and a half and then actually shaved the top of the concrete slab about a half inch to three quarters in some places to gain additional setting bed depth so that the new stone would have a chance of lasting longer than the previous stone.

Then of course state of the art waterproof membrane and all that on it.

There were places that had been so bad that we had through slab repairs, this is actually in the lobby space, that's how the bad that this had deteriorated which meant of course we had to replace stone along there as well.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

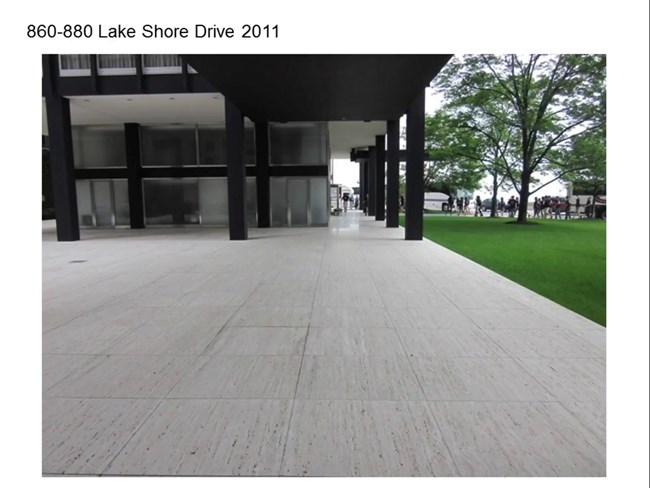

Once we had everything, all the ducks in a row so to speak, the installation went quite well.

These are those valley pieces I talked about that had to be laid in first. These guys were great, they really knew their stuff, they were incredibly efficient and good and cared about what they were doing.

This guy not so much but we got through that.

Again it required being there a lot, here they are putting in the big pieces of glass.

Again they had replaced all the original sandblasted glass with laminated glass, we went back to the sandblasted glass and used low light … What do you call it … I'm having a … Low iron glass sorry.

I'm going off script.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Here you see in the right the new and the old.

There is a difference, we tried very hard to get it as close as we could but there was still a telltale difference but I think the effect is very minor.

When you are there it looks beautiful and just as it did when Mies finished it.

Here you don't see the difference in the elevation on the left between the inside and the outside even though it is up an inch and a half.

Some finished images.

Here if you really look hard you can see that there's some slight slope in some places but it is basically imperceptible and it functions.

There are a couple of places that as I mentioned there's this interface on the left, that's an inside space with new and old.

Then you can sort of see it.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

On the outside it's a little more pronounced and we took some of the … The best we could find of the original travertine of which there wasn't a heck of a lot but we took that and installed it along back at one building near the loading dock.

The difference in the weathering was significant and we did not rehone the old stone.

That's what you see in the top of the right picture there.

Here's a whole patch of it so you can see the old and the new together.

We think Mies would be pleased.

I just want to finish up with a couple of things.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

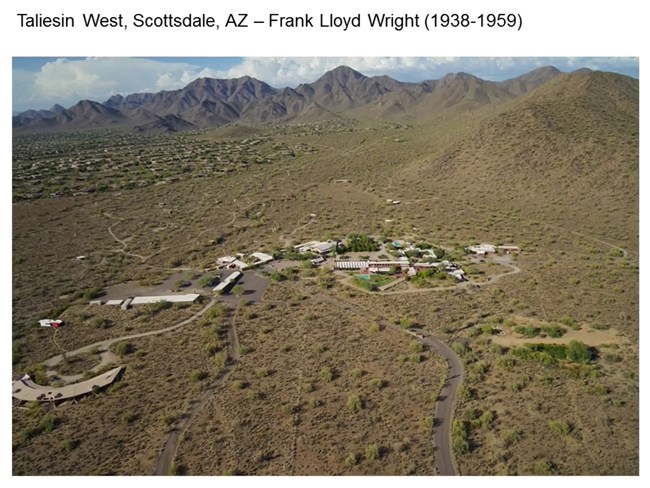

Frank Lloyd Wright: Taliesin West

What we are on to now and so from Mies to Mr. Wright.

I'll tell you what we are up to right now. We are working out at Taliesin West.

We are very excited and honored to be working there as many of you have heard the Key Works of Modern Architecture by Frank Lloyd Wright has been submitted to the World Heritage Committee which includes ten sites Unity Temple, Robie House, Taliesin, Hollyhock, Fallingwater, Jacobs House, Taliesin West, Guggenheim, Bartlesville Tower and Marin County Civic Center.

Sort of a [Frank Lloyd] Wright's greatest hits.

We are very honored that we are currently working on three of these, Unity, Robie and Taliesin West.

The first two I won't talk about, those are not mid century but they are a lot of fun.

In fact Unity is under construction in about two weeks, full restoration.

We are just finishing up a major preservation master plan for Taliesin West, it's a tome of about close to 600 pages.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

This project has very difficult questions and they all need to be addressed properly for the care and sustaining of Taliesin West.

All that it was, all that it currently is, and all that it wants to be.

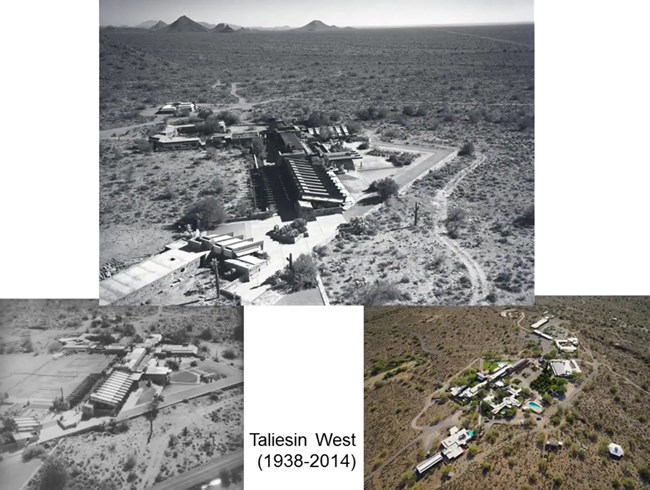

It was the winter camp for the Taliesin Fellowship that Wright had started in 1932 in Wisconsin.

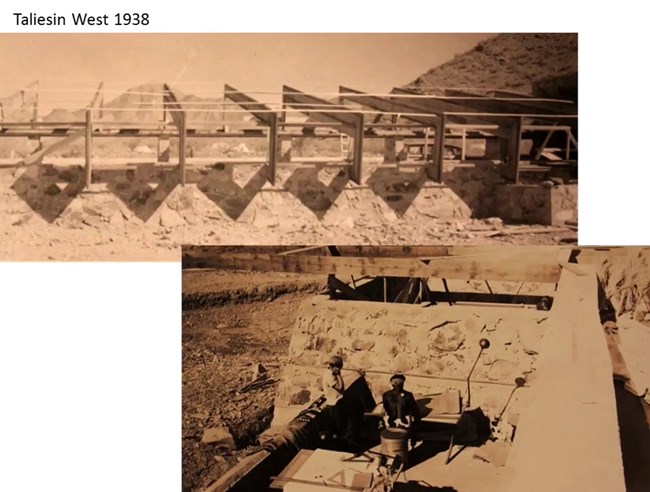

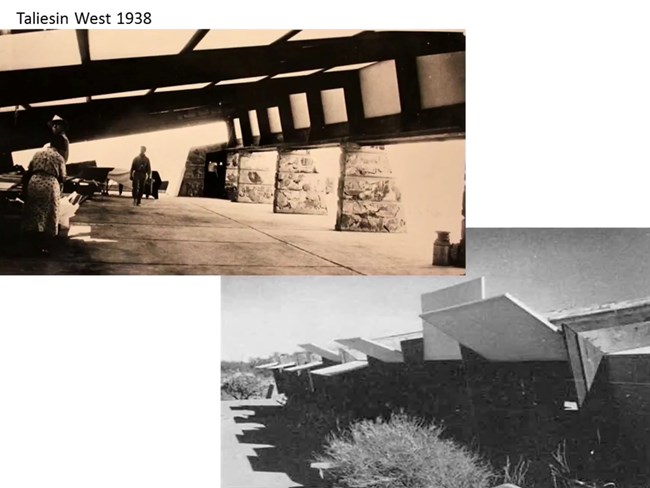

After a long search he found some land in Scottsdale and started to build in 1938.

Nearly every winter for the rest of his life he would take the fellowship to Taliesin West between November and April and he would build the building at the site and he would work on whatever projects he had in the office at the time.

In the beginning he had no work so that's all they did was work on Taliesin West.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Each time they arrived Wright would make changes or additions to buildings.

He didn't stop until his death in 59.

It is very poorly documented.

We have some great … There's still some of the fellows alive that were there in the late 40s and they tell stories of Mr. Wright, he would come and say, “You all go and put a window over there.” Or whatever and so Joe would go put the window over there and no-one knows how or why or what but he figured it out.

If he didn't like it he tore it out and did it again. That went on all the time.

Figuring that out when it happened, how it happened and the things that we want to know in such a report is a little bit challenging but it has been a lot of fun.

In fact, this is the most fun and the most challenge that I think I've ever had in my career so I'm very excited about it.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Of course the big challenge is to find out how to make this rustic camp and that's right in the lower picture that's him drawing at the drafting board.

They were outside a lot here and when they were inside they were outside.

This is the original concept of this place.

It lasted for about ten years this way, more or less this way.

Of course there's a rich social history there, interesting and complicated.

Then on the right see what it looks like today.

The question or some of the questions are how to find a way to allow this rustic camp that was Taliesin West for its first decade to read through all the change that has occurred since the second decade and beyond.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

Because after his death in 59 his wife, Olgivanna Wright and son-in-law Wes Peters continued to make change to try to make it more habitable all year round which changed a lot of things about how that place looked and how it functioned.

How do we do that in a way that doesn't create a false sense of history?

Or doesn't create too great a compromise on how the buildings get used?

Because the school is still there and still used.

It is visited by 120,000 visitors every year.

How do we do that and still be able to tell this important story

That's a complicated issue so stay tuned on that.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

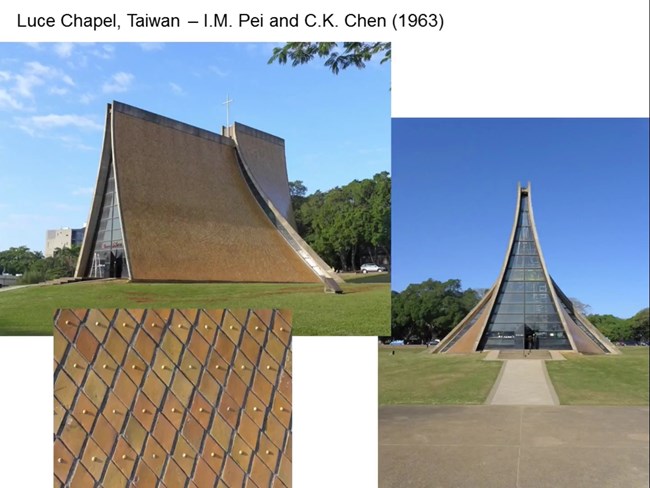

the Luce Chapel at Tunghai University in Taichung, Taiwan, China

One last thing I'll mention that I'm currently working on.

I'm consulting on a little project which is a lot of fun, this is the Luce Chapel in Tunghai University in Taichung in Taiwan, China where I'm serving as a consultant.

And this was originally designed by I.M. Pei and C.K. Chen in the mid 1950s but not built until 1963.

I don't know if any of you have seen this before, I wasn't really familiar with it myself but it's a gorgeous little chapel.

I think it does sort of qualify as a brutalist building but it's really too pretty to have that name given to it because it is all concrete.

But wonderfully formed and beautifully articulated and the photographs of it being constructed with all these bamboo scaffolds and form work is really amazing.

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, Harboe Architects

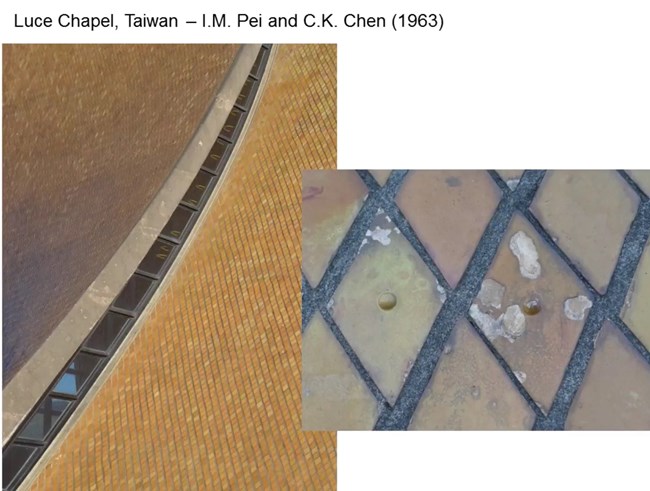

But it has some problems, the usual … The concrete is actually in pretty good shape.

There's some steel problems with the curtain wall but it's really big problem is the tile.

This beautiful glistening scaly surface tile is failing on many of them which is probably something just inherent to the way it was made.

So I'm asking the question to this great group out here that if any of you have this issue or had to deal with a similar issue of how to help to mitigate this I don't think it can really be fixed but it can perhaps be made to last longer.

I'm open to suggestions because it would be really hard to cut these out and put new ones in even if you could make them to look just like it.

This is the big dilemma.

With that I am going to wrap it up, I will say again for those of you that have your smart phones, you can turn them on again soon and go out and join Docomomo. Thank you.

Learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.

Chicago Magazine

[Image links to Chicago Magazine Article: How Gunny Harboe is Restoring Frank Lloyd Wright's Most Notable Works.]

Biography

Gunny Harboe, FAIA, is a registered architect with over 25 years of experience and currently runs his own small firm, Harboe Architects, PC.

He received his M. Arch. from M.I.T., (including study in Copenhagen, Denmark); a M.Sc. in Historic Preservation from Columbia University; and an A.B. in History from Brown University.

Harboe gained a national reputation for his award winning restorations of the Rookery Building and Reliance Buildings and has been the preservation architect for many iconic modern masterpieces including Mies van der Rohe’s S.R. Crown Hall and 860-880 Lake Shore Drive Apartments; Frank Lloyd Wright’s Robie House, Unity Temple, and Taliesin West, and Louis Sullivan’s Carson Pirie Scott & Co. Store.

Harboe was named a “2001 Young Architect” by the National AIA, and “Chicagoan of the Year” by Chicago Magazine in 2010.

A founding member of DOCOMOMO_US, he was also a Regional Director of AIA National, and President of AIA Chicago, and a founding member and current Vice President of the ICOMOS ISC on 20th Century Heritage. He is also an Adjunct Professor at IIT.

This presentation is part of the Mid-Century Modern Structures: Materials and Preservation Symposium, April 14-16, 2015, St. Louis, Missouri. Visit the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training to learn more about topics in preservation technology.