Last updated: November 3, 2022

Article

Mammoth Cave Core Visitor Services Area Cultural Landscape

NPS / Mammoth Cave National Park

Introduction

Established in 1941, Mammoth Cave National Park encompasses 52,830 acres in southcentral Kentucky including the longest known cave system in the world as well as the surrounding river valleys, karst topography, and rolling, wooded hillsides. Embedded therein is the visible record of a 12,000-year conversation between people and land spanning the first explorations by prehistoric people, early mineral mining, pioneer homesteading, preparations for the War of 1812, and 200 years of tourist-driven boosterism leading to the establishment of a national park.

The Core Visitor Services Area today functions as the literal and figurative heart of Mammoth Cave National Park – the hub at which lodging, transportation infrastructure, and other amenities key to administering the visitor experience are located.

Landscape Description

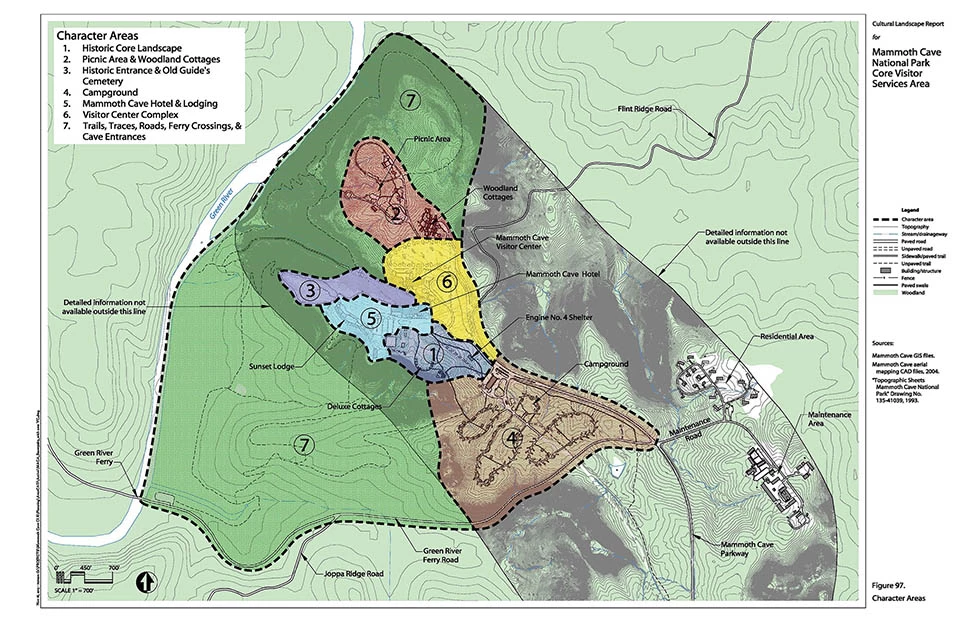

Character-defining features of the Core Visitor Services Area include New Deal and Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) era architecture and landscaping, tourist amenities dating to the early 19th century, and the original natural entrance to Mammoth Cave. The Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) for the Core Visitor Services Area, completed in 2016, identifies seven discrete landscape character areas, defined by their unity of features or land use.

Core Visitor Services Area

Left image

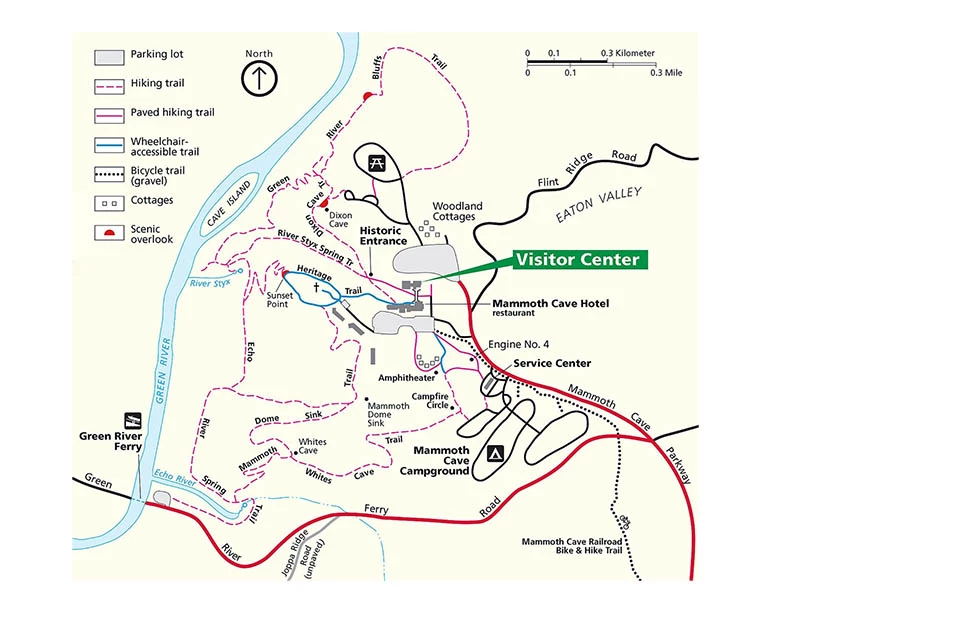

Park map of the Core Visitor Services Area.

Credit: NPS / Mammoth Cave National Park

Right image

Seven character areas of the Core Visitor Services Area.

Credit: NPS / CLR for Mammoth Cave Core Visitor Services Area

NPS Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) for Mammoth Cave Core Visitor Services Area

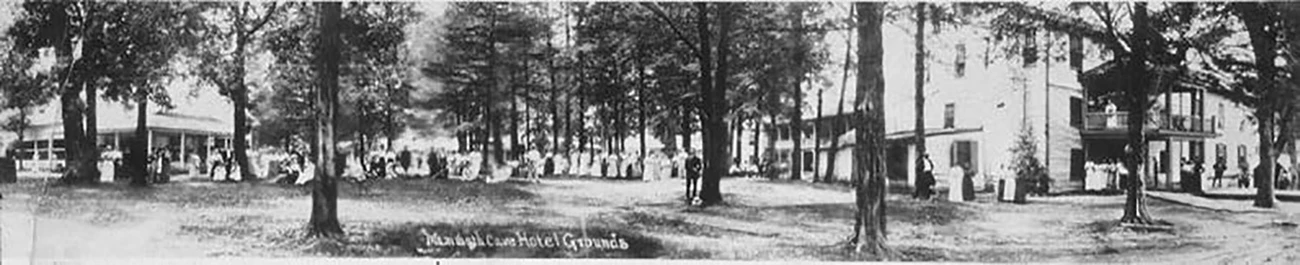

Historic Core Landscape

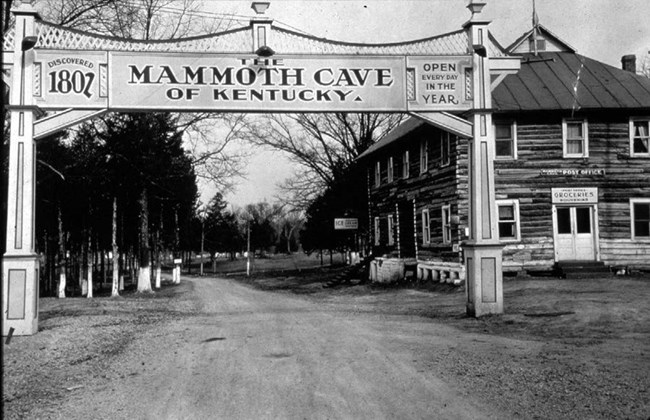

The Historic Core Landscape Character Area includes a large cedar grove marking the site of the original Mammoth Cave Hotel, constructed in the early 19th century and lost to a fire in 1916. A second Mammoth Cave Hotel replaced the original in 1925 and continued to host park visitors until 1979. The Deluxe Cottages were completed in 1937 to accompany the second hotel. The Historic Core also includes the site of the circa 1920s and 1930s arch entrance to the park, as well as the Engine No. 4 and Coach No. 2 interpretive exhibit and remnant railroad bed – relicts of the Mammoth Cave Railroad, a key mode of access to the park from 1886 to 1936.

Left image

Eastern red cedars lined the path between the 1925 hotel and its associated yard, date unknown.

Credit: NPS / Mammoth Cave National Park

Right image

Today, this grove of cedar trees remains as one of the few relicts denoting the location of the 1925 hotel. Four of the trees in this photograph survive from the historic view.

Credit: NPS / Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) for Mammoth Cave Core Visitor Services Area, Mammoth Cave National Park (2016)

NPS Drawing No. 135-2025D

Picnic Area and Woodland Cottages

The Picnic Area and Woodland Cottages, located north of the Mammoth Cave Visitor Center, have served park guests since the late 1930s. The Cottages were completed in 1939 by Nevin, Morgan, and Kolbrook Architects and Engineers of Louisville, Kentucky, with adjacent landscaping and supporting infrastructure installed by the CCC. The picnic area was originally constructed as a campground by the CCC between 1940 and 1941. A comfort station, two picnic shelters, an enclosed picnic shelter building and a building known as the Earth House were later adapted for the purposes of the current picnic area. In 1949, it was expanded to include bathing and laundry facilities, and it now functions as an environmental education center.

NPS / Mammoth Cave National Park

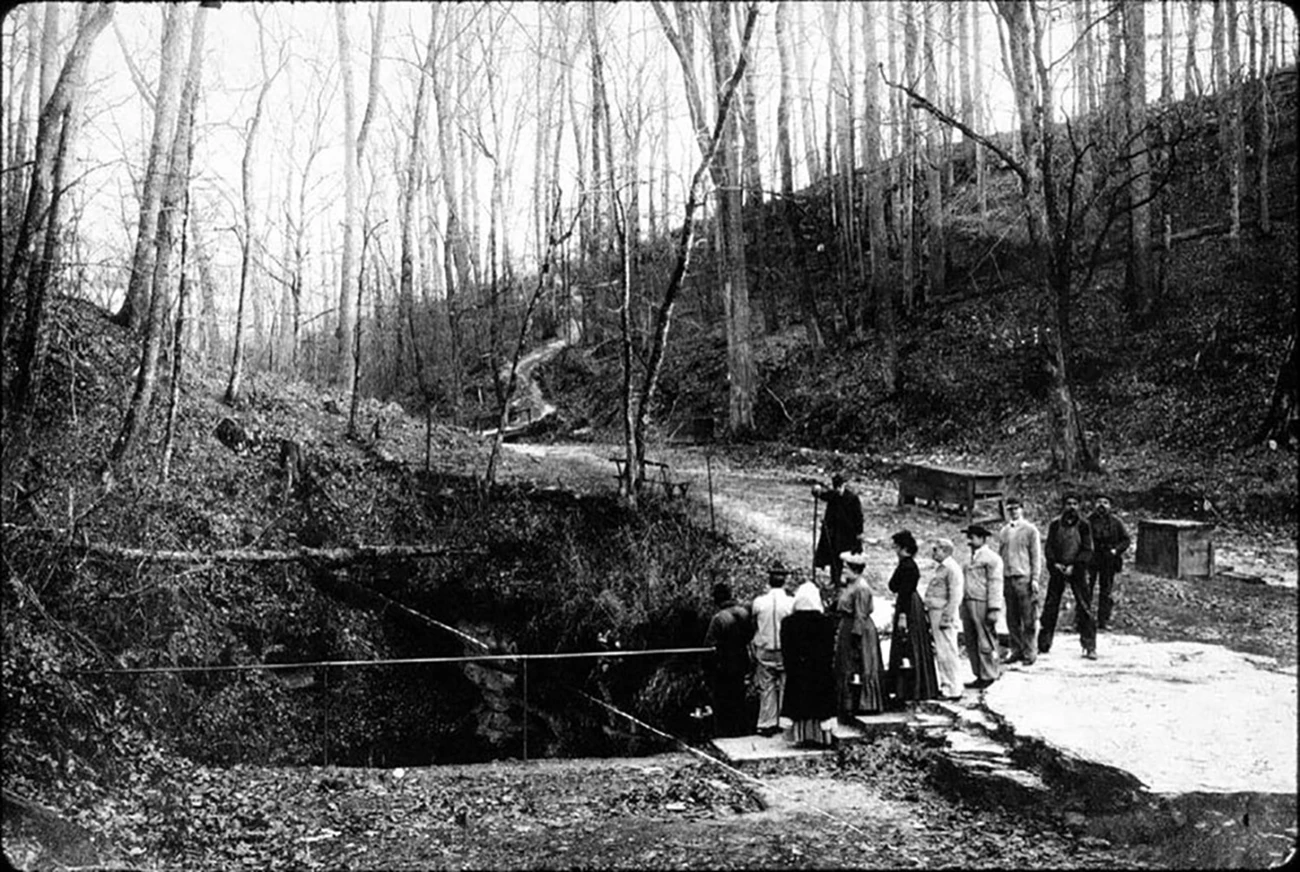

Historic Entrance to Mammoth Cave & Old Guide's Cemetery

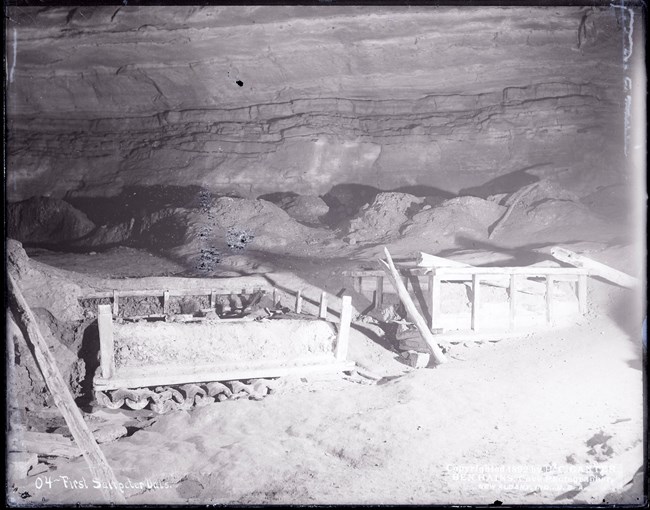

The Historic Entrance to Mammoth Cave and the Old Guide's Cemetery together comprise the third character area. The Historic Entrance is the original visitor entrance to the cave as well as the site of a previous processing area that transformed guano-rich soil mined from inside the cave into saltpeter.

As visitors approach and exit the caves, they must walk over a series of bio-security mats – a measure intended to protect the cave’s resident bat population from white-nosed syndrome.

The Old Guide’s Cemetery, located on a hill above the Historic Entrance, is part of the Heritage Trail loop and features the grave of Stephen Bishop, an enslaved cave guide famous for establishing routes through many previously uncharted parts of the cave. The Cemetery also includes the graves of former patients of Dr. John Croghan, whose ill-fated attempt to avail thirteen tuberculosis patients of their symptoms through prolonged exposure to the cave’s cool microclimate resulted in seven deaths by the experiment’s termination in 1843.

NPS / Mammoth Cave National Park

Stephen Bishop's extensive experience exploring and guiding visitors through previously uncharted reaches of Mammoth Cave made him as conversant in geology and minerology as many professors of his day. Bishop continued leading tours and discovering new passages in Mammoth Cave until his death in 1857 at the age of thirty-seven. His remains were initially interred in an unmarked grave near the historic entrance to Mammoth Cave.

In 1881, an unclaimed Civil War tombstone was procured by the millionaire James R. Mellon to commemorate Bishop's life and contributions. The original honoree's name had to be scratched out for this purpose, and Bishop's date of death is mistakenly listed two years after the fact. Today, Bishop's gravesite remains a characteristic feature of the Old Guide's Cemetery and one of its most famous interments.

Campground

The Campground character area was constructed in 1964 as part of the Mission 66 program and features four camping loops with a total of 111 individual pull-off campsites. Additional amenities comfort stations, a service center building with a post office, camp store, office space for concessionaires, a campfire circle, and an amphitheater.

NPS / Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) for Mammoth Cave Core Visitor Services Area, Mammoth Cave National Park (2016)

Mammoth Cave Hotel & Lodging

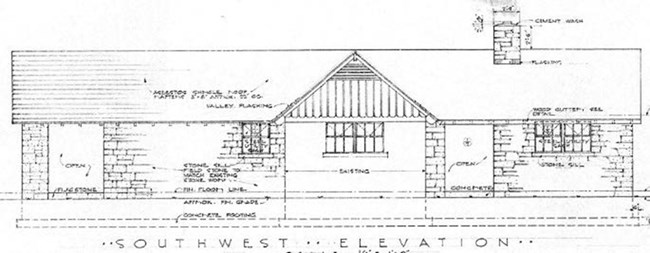

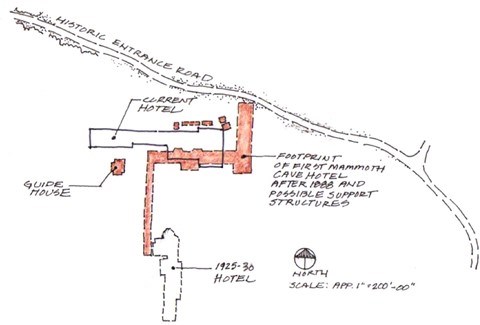

The Mammoth Cave Hotel and Lodging character area consists of the existing Mammoth Cave Main Hotel Lodge, Heritage Trail Rooms wing, Sunset Lodge, concessionaire dormitory and laundry, pet kennels, and associated parking and pathways. A small pedestrian bridge connects the visitor center to the hotel.

The existing hotel, constructed in 1965, stands atop the location of the first Mammoth Cave Hotel. As such, this character area bears traces of multiple eras of tourism at Mammoth Cave National Park spanning the 19th century to the present.

Diagram courtesy of JMA historical landscape architects

Visitor Center Complex

The Visitor Center Complex character area was developed between 1959 and 1961 as part of the Mission 66 program and has received numerous upgrades since then, including an extensive renovation undertaken between 2007 and 2012.

Trails, Traces, Roads, Ferry Crossings, and Cave Entrances

Finally, the Trails, Traces, Roads, Ferry Crossings, and Cave Entrances character area encompasses the extensive trail system associated with the visitor center area, historic roads and road traces, the old ferry crossing, and the existing Green River Ferry crossing and two cave entrances, Dixon Cave and White Cave. Most of this area is characterized by dense woodland tree cover, spectacular views of the Green River Valley, and access to the Green River.

Left image

This 1941 photograph provides a north-facing view of Green River Ferry Road, two years after its construction by the CCC.

Credit: NPS / Mammoth Cave National Park

Right image

Today, the Green River Ferry crossing still functions as a key gateway to the Core Visitor Services Area.

Credit: NPS / Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) for Mammoth Cave Core Visitor Services Area, Mammoth Cave National Park (2016)

NPS / Mammoth Cave National Park

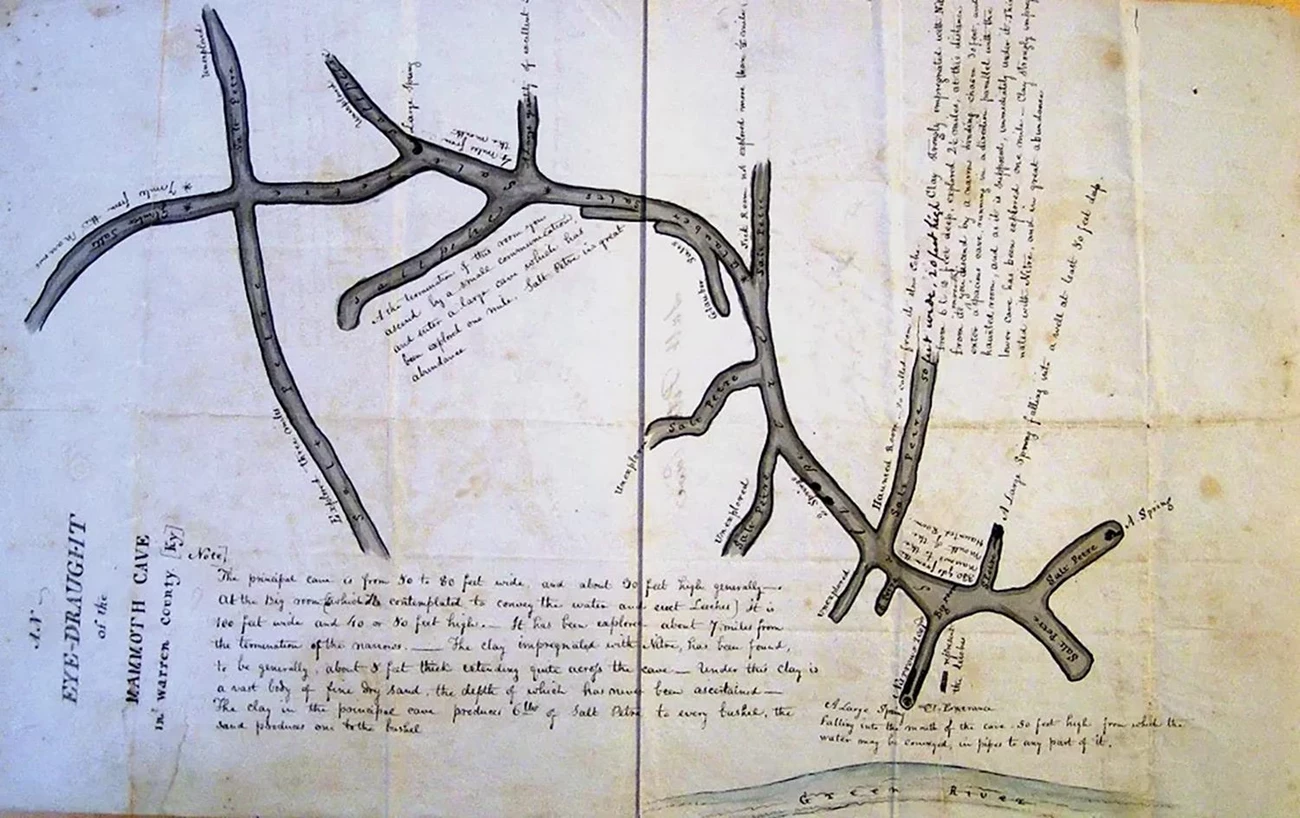

Historic Use

Archaeologists propose that people first began exploring Mammoth Cave between 5,000 and 4,000 BCE. The archaeological evidence suggests that most took to the caves for the minerals they contained, namely gypsum – the same mineral used in drywall and sidewalk chalk – as well as mineral salts like epsomite and mirabilite. What value these minerals held to prehistoric people remains unclear – archaeologists speculate that they may have been imbibed as medicines, applied as agricultural amendments, traded for other goods and commodities with neighboring tribes, or used as pigments.

This desire to draw mineral wealth from the cave’s interior persisted well after prehistoric people ceased to venture there. For a time, however, the land around Mammoth Cave was considered marginal – a deed from 1798 refers to it as “second-rate land.” This same deed, however, also alludes to resources yet to be exploited – namely, two good “peter caves” located on this same property. “Peter,” in this case, referred to saltpeter, or potassium nitrate – a compound leached from the millennia’s worth of guano deposited by the caves’ resident bat populations.

NPS / Mammoth Cave National Park

These reserves were a key strategic resource for the U.S. military during the War of 1812, ensuring that the United States a domestic supply of gunpowder. As with most other areas of the economy, this industry was also wholly dependent on the labor of enslaved African Americans, who harvested the guano-rich soil from inside cave for further processing.

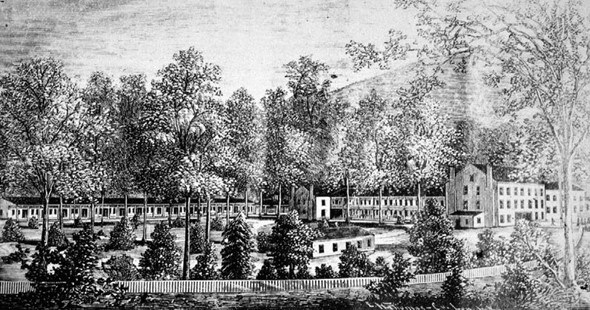

With the end of the war, tourists began to visit in response to discoveries made inside the cave, particularly the discovery of a prehistoric woman’s remains near the mouth of what is now known as Short Cave. The discovery of these remains, as detailed in a widely publicized account at the time, sparked a century-long tourism boom.

NPS / Mammoth Cave National Park

Throughout the 19th century, people journeyed to Mammoth Cave to venture into its depths, drawn by the prospect of encountering “Indian mummies” and other curiosities and novelties.

Tourism would dominate over the next two hundred years, bringing with it a wave of boosterism that would leading to the expansion of ferries, stagecoach lines and railroads, the construction of the hotels, rustic cottages, and other amenities necessary for the operation of a profitable tourist industry in an expanding market economy.

The Mammoth Cave Railroad served visitors to Mammoth Cave from 1886 to 1931. The railroad used steam engines until 1929, after which they were replaced by a rail bus. A steam engine was again used for the final run of the railroad in 1931.

NPS / Mammoth Cave National Park

As in other areas of the economy, this industry was reliant on the labor of enslaved African Americans, who were employed as housekeepers, cleaners, cooks, laborers, and guides. By their handiwork, the landscape of the Core Visitor Services area continued to change, with the construction of new buildings, the expansion of trail networks further into Mammoth Cave’s depths, and exploration of heretofore uncharted passages.

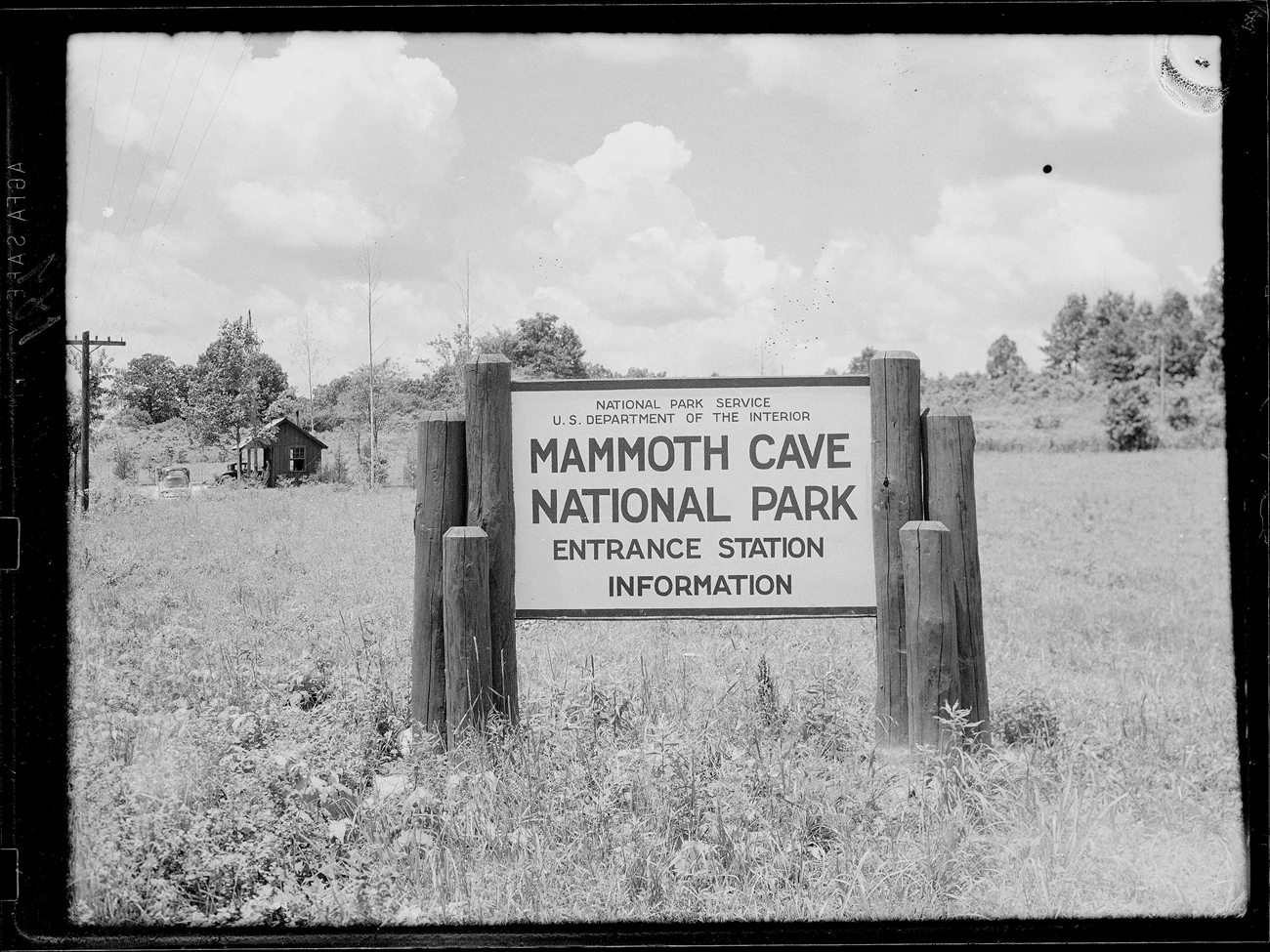

The idea of establishing a national park at Mammoth Cave was first broached by representatives of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad in the late 1880s, who thought that designation would boost tourism revenues. Following a visit to the Cave in May 1925, the Southern Appalachian National Park Commission recommended the establishment of a national park. Enabling legislation was passed in 1926.

NPS / Mammoth Cave National Park

Though no federal funding was allocated toward acquiring land for the new park, a combination of new legislation, land donations, purchases, and acquisitions by eminent domain enabled its establishment. Land acquisition by eminent domain notably displaced residents who had maintained small farmsteads on the thousands of acres of land surrounding the historic core of the park.

Thereafter, the National Park Service (NPS) assumed full responsibility for the park. Its official dedication was postponed until 1946, however, due to U.S. involvement in World War II.

Landscape Changes

NPS / Mammoth Cave National Park

Despite limited federal funding, initial work commenced in the mid-1930s with the help of over $400,000 in tourism revenue raised by the Mammoth Cave Joint Operating Committee, which the NPS used to fund improvements by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Four CCC camps operated at the park between 1933 and 1942. Each camp housed 200 to 250 enrollees and was composed of several buildings including three to four barracks, a kitchen and mess hall, latrines, and maintenance areas. These facilities were also segregated, with Black enrollees mostly enlisted to work in separate, Black-only companies.

The improvements implemented by the CCC would bring about a dramatic transformation. Prior to this work, the area of the park was rugged, with scattered cleared areas for farms. By “naturalizing” the landscape following acquisition of these properties, the CCC effectively erased any trace of prior habitation.

NPS / Mammoth Cave National Park

In all, CCC crews constructed 65 miles of paved roads, 7 miles of trails, three steel-framed fire watchtowers, and two ferry boats. Erosion control was implemented along streams, with hundreds of check dams. More than 600 trees were planted, and cave entrances were restored to a naturalistic state. Parking areas were landscaped with ornamental trees and shrubs. Approximately 1,700 former farm buildings in the park were razed, and 300 miles of fence were removed.

CCC laborers also constructed the park maintenance complex (1939–1941), a six-building housing complex for park employees (1937), a home for the Park Superintendent (1941), a chlorinator house (1940), and ranger station facilities (1942), carried out small renovations at the existing Mammoth Cave Hotel and added tennis and shuffleboard courts to the area west of the hotel in 1938.

NPS / Mammoth Cave National Park

Infrastructural improvements necessary to support these new amenities included two water systems encompassing four 50,000-gallon concrete reservoirs, two pumping stations, and 4 miles of cast iron water mains, two sewer systems, and a phone system. Within Mammoth Cave, CCC enrollees added handrails, bridges, and constructing 8 miles of trails throughout the cave to improve the visitor experience.

By 1941, as the New Deal era activity at Mammoth Cave drew to a close and the park was officially established, the core area had been noticeably transformed. Where inhabited farmland had stood before, the Core Visitor Services Area now stood ready to welcome a new era of visitation to the newly established national park.

NPS / Mammoth Cave National Park

NPS / Mammoth Cave National Park

Preservation and Treatment

In order to appropriately manage the Core Visitor Services Area, the National Park Service engaged the team of preservation professionals to prepare a Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) to help guide the design and implementation of proposed changes, as well as the repair and rehabilitation of features now and in the future.

The overarching treatment philosophy articulated in the CLR is to balance the protection and enhancement of the site’s historic integrity with contemporary park visitor access and interpretation needs within a broader framework of sustainable land management. Rehabilitation is the recommended treatment approach, with specific actions aimed at improving the functionality, appearance, universal accessibility, and appreciation of history at the site as well as to address pressures to accommodate large crowds of visitors.

NPS / Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) for Mammoth Cave Core Visitor Services Area, Mammoth Cave National Park (2016)

Treatment also focuses on maintenance practices that enhance the historic landscape. Over the years, the popularity of Mammoth Cave has taken its toll on many areas within the historic core. For example, one treatment recommendation focuses on rebuilding the Old Guide’s Trail when washouts occur after heavy rains. By mitigating erosion of historic trail networks within the Core Visitor Services Area, park managers also ensure visitor accessibility while protecting these resources’ ability to convey the historic significance and character of the site.

Conclusion

The Core Visitor Services Area at Mammoth Cave National Park embodies a 12,000-year conversation between people and the landscape of southeastern Kentucky. Most acutely, the site also illustrates the degree to which visitors’ experience of Mammoth Cave is mediated – as much an artifact of human intervention as the landscape itself.

NPS / Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) for Mammoth Cave Core Visitor Services Area, Mammoth Cave National Park (2016)

Quick Facts

-

Cultural Landscape Type: Historic Designed

-

National Register Significance Level: National

-

National Register Significance Criteria: A

-

Periods of Significance: 1806–1941