Part of a series of articles titled Whose Story is History? The Diverse History of Grand Canyon.

Article

Lumber, The Green Book, and Grand Canyon

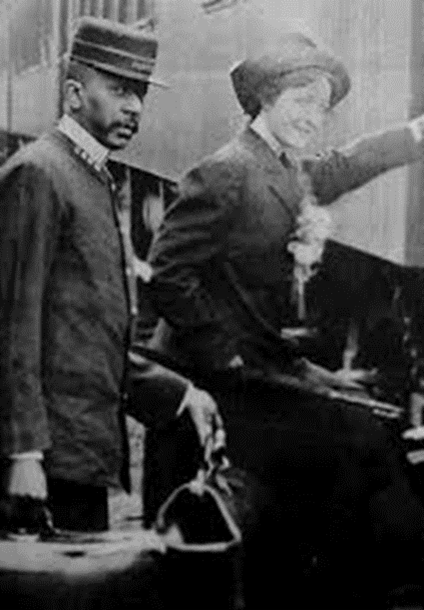

VIRGIL GIPSON

WILLIAMS PUBLIC LIBRARY, HOFFMAN COLLECTION

While Fred Harvey hired many people of color, they were often relegated to lower paying service positions and were subject to segregation in areas where discrimination persisted. Harvey hired Black Americans such as Percy Tyler as a stationary engineer. Many Black men also worked on the railroad as porters. A Black man called “Uncle Charlie” worked as a bartender at El Tovar from its opening in 1905 and worked there for many years. Some men of color were able to move up the ranks. Tim Cooper, an African American man, was Harvey’s assistant through the 1880s and 1890s. He was the oldest and longest tenured employee with Fred Harvey Company when he retired.

The increase in railroad tracks and infrastructure required a greater need for lumber as well. Many African Americans worked as skilled logging men in Southern States for decades. Deforestation spread through the South and wages plummeted. Many Black Americans looked for work elsewhere. The dense forests of Northern Arizona provided opportunity for better wages and a possible relief from the Jim Crow culture of the South. Beginning in the 1920s, but reaching peak migration in the 1940s and 1950s, many Black Americans moved to Northern Arizona. They moved from states like Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi, and more.

NAU CLINE LIBRARY

In order to travel safety from Southern states to Arizona, many Black laborers traveled by train. If it was possible, some would travel together by automobile. This gave some freedom to people migrating, but it also created other challenges. Racial discrimination was widespread during this time, and hotels and restaurants could refuse service to Black patrons. Even finding a restroom could prove incredibly challenging. When James W. Williams was driving west in 1942 with three other lumber workers, he experienced these problems firsthand.

When asked if his trip was peaceful, James W. Williams said, “Peaceful, yeah. Such as people could be. At that particular time, you couldn’t sleep or eat anyplace. You had to get a store-bought lunch if you were going to eat, no cafés. You could go to a café, but you had to go around back…. You’d have to drive all night and have to look for the colored part of town, maybe you could find a room... We never slept in a hotel or motel.” Williams and his travel companions had to sleep in the car on the side of the road. These challenges not only affected the men traveling for work, but their families who followed soon after. 1

NAU CLINE LIBRARY

Sources:

1 Reid, Jack. "The 'Great Migration' in Northern Arizona: Southern Blacks Move to Flagstaff 1940–1960." The Journal of Arizona History 55, no. 4 (2014): 469–498.

Hangan, Margaret. "Finding African American History in the West." KIVA: Journal of Southwestern Anthropology and History 86, no. 2 (2020): 149-155.

"Oral history interview with James W. Williams" by Carol Maxwell. African American Pioneers in Flagstaff Oral History Collection, Cline Library, Northern Arizona University, 2002. https://archive.library.nau.edu/digital/collection/cpa/id/21136/.

Reid, Jack. "'I Wanted to Get Up and Move:' The Arizona Lumber Industry and the Great Migration." Forest History Today 27, no. 1&2 (2016): 4-13. https://foresthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Reid.pdf

Last updated: October 11, 2024