Part of a series of articles titled People of the Mormon Pioneer Trail.

Article

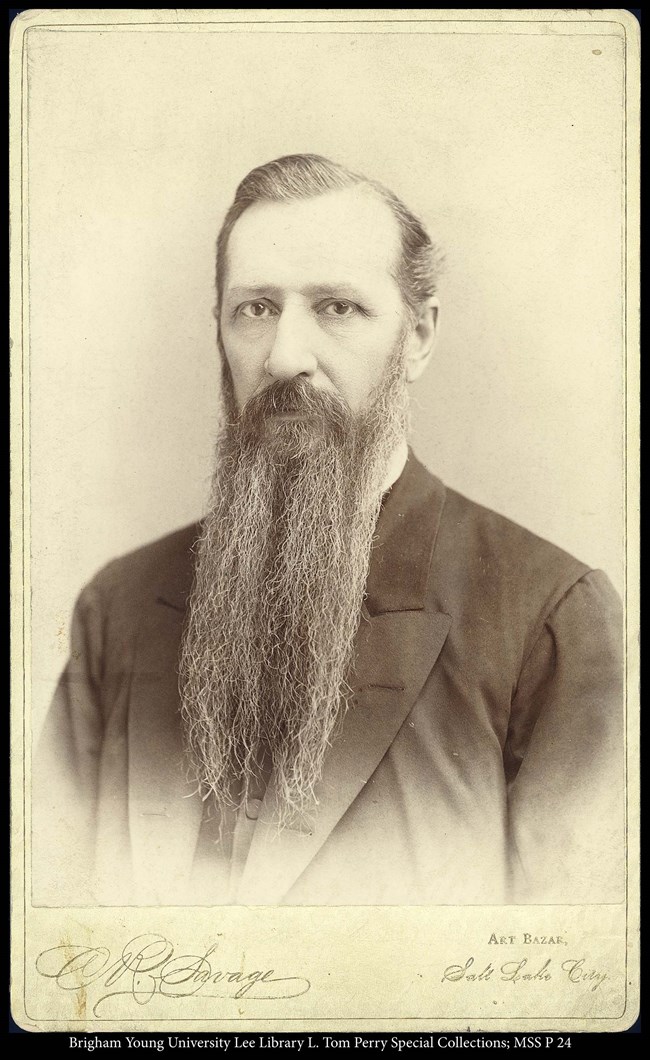

Joseph Fielding Smith, the Mormon Pioneer Trail

Photo/Public Domain

Joseph Fielding Smith – Mormon Pioneer Trail [1]

By Angela Reiniche

Joseph Fielding Smith, sixth president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the nephew of its founder, Joseph Smith, was born in Far West, Missouri, on 13 November 1838. Tensions between the members of the Latter-day Saints and neighboring settlers, who took issue with certain Mormon beliefs and behaviors, increased steadily after the church dedicated its temple site in 1831 at Independence, Missouri. About two weeks before the birth of Joseph Fielding Smith, Governor Lilburn Boggs issued Missouri Executive Order 44, ordering all Mormons to leave the state under the threat of extermination. Joseph Fielding’s father, Hyrum Smith, missed his son’s birth because he had been arrested and jailed in Liberty, Missouri, along with his brother, church founder and prophet Joseph Smith. Soon after his birth, most of the Missouri-based Mormons fled to Illinois, where they would build an interim home at Nauvoo and wait for the call to return to Missouri. Mary Fielding Smith, Joseph Fielding’s mother, left Missouri with her infant son and the five children from her husband’s first marriage in her care. In 1839, shortly after escaping from jail, Hyrum joined his family in Illinois.[2]

Over the next six years, the church focused on its new community in Nauvoo, Illinois. All the while, Joseph Smith promised that church members would be able to return to Missouri. The church’s neighbors in the Nauvoo area eventually grew wary of the Mormons’ activities, their business practices, Smith’s political aspirations, and the implied threat of his well-drilled and sharply outfitted Nauvoo militia. Violence broke out on 27 June 1844, when Joseph and Hyrum Smith were killed by local vigilantes while jailed at Carthage, Illinois. At the age of six, Joseph Fielding Smith had lost both his father and uncle, and the young church had lost its foremost leaders. In the aftermath of their deaths, violence continued to haunt Nauvoo while the Latter-day Saints faced a controversial succession crisis. Brigham Young, one of Smith’s most trusted associates, eventually assumed the leadership of the main body of Latter-day Saints and, as early as 1845, announced plans for the church’s westward migration.[3]

By the spring of 1846, the city of Nauvoo had been transformed by more than two years of violent conflict and the massive undertaking of leaving Illinois. Joseph Fielding Smith later recalled how many of the buildings in Nauvoo had been converted into storage for supplies and into shops where they built wagons, harnesses, and anything else necessary for the journey.[4] Under Young’s leadership, the initial exodus from Nauvoo began in February, followed by several waves of evacuees in April, May, and June. Because of the partial evacuation, a mere three hundred Latter-day Saints remained in Nauvoo and were present for the public dedication of their temple on 1 May 1846. By this time, the violence in and around Nauvoo had risen to such a level that the widowed Mary Fielding Smith, as she had eight years earlier in Missouri, decided to flee her home for the safety of her children, which by then included her and Hyrum’s six-year-old daughter, Martha. After exchanging all of their Illinois property for a wagon and a team of oxen, the Smith family, along with many other Mormon families, left Illinois behind and started toward the temporary encampment established at Winter Quarters, Nebraska. By the time he turned eight years old, Joseph Fielding Smith had experienced myriad trials, but the journey ahead, along what became known as the Mormon Pioneer Trail, offered hope for a less chaotic and disruptive life.[5]

Joseph Fielding Smith and his family spent more than a year at Winter Quarters waiting for the rest of the Saints to gather. Every day the entire camp busied itself with the preparations for their mass emigration to the West. Fielding Smith kept company with the large number of children, all of whom had responsibilities that included tending livestock, cooking, watching over their siblings, and doing anything else their elders deemed necessary. Fielding Smith later recalled a day during which his chores could have caused his own death. While he and Thomas Burdick, another boy from the camp, were out on horseback watching over the cattle herd as it grazed, Joseph saw a band of American Indians riding toward the herd. While Burdick returned to the camp to get help, Joseph placed himself between the potential marauders and the cattle and tried to push the herd back toward the settlement. A stampede ensued and Fielding Smith lost his horse in the melee, but he managed to survive the ordeal once help arrived.

In the spring of 1848, nearly two years after Joseph Fielding Smith and his family’s arrival, the many thousands of Latter-day Saints encamped at Winter Quarters organized into companies in preparation for the journey to Utah’s Salt Lake Valley. Mary Smith’s family was assigned to Heber C. Kimball’s company. The young Fielding Smith did not keep a personal journal of the overland trip, although several other members of the Kimball company did. The sheer size of the mass migration required extensive organization and planning, which meant an equally extensive paper trail of rosters, supply lists and costs, route maps, and correspondence. Later in his life, Fielding Smith recorded his own recollections of the journey, which were dominated by memories of his widowed mother’s financial hardships and the indifferent, perhaps ill-intentioned, treatment they faced at the hands of their company captain, Cornelius Peter Lott. In the journal that Joseph Fielding Smith kept later in life, he recorded more personal recollections, which included a difficult crossing at the Elkhorn River. The wagons had sunk into the sand and had to be dragged out by “what might have appeared to onlookers as two armies encamped on either side of the river waiting the signal for conflict.” Despite this appearance, Fielding Smith described a happy ending: “… but how different was the case when almost the whole strength of one [helped] their friends.”[6]

After their treacherous crossing, Fielding Smith described details of the flora and fauna he encountered as they neared the Platte River below Fort Laramie. He remarked, “how wonderful to see the buffalo . . . for several hundred miles the prairie is covered with their dung from which one is sure there must be thousands of them”; he also noted that “we ate freely of the flesh and dried great quantities, [which we] brought to the Valley.”[7] Fielding Smith also added that many of their oxen perished after eating the saltpeter that covered the ground. Their company crossed “mountains of sand,” met with friendly Native Americans, and forded several small streams and creeks, including the Green, Bear, and Weber rivers, as they neared the Salt Lake Valley. Fielding Smith wrote that the last forty or fifty miles of road were “shocking bad” and mused, “I wonder that so little damage was sustained, it seems a wonder that any wagon can stand it.”[8] The party arrived in the Salt Lake Valley on 24 September 1848, almost four months after their departure from Winter Quarters.

Joseph Fielding Smith later recounted how their captain had treated his mother. Early in their journey, just before crossing the Elkhorn River, it became obvious that the Smith family’s two yoke of oxen would have continuing difficulties crossing the plains. The church agent to whom Mary Smith applied for assistance refused her request and advised her to turn back lest she become a burden to her company. The widowed Mary Smith and her brother, also named Joseph, arranged to borrow some oxen and returned to their company fully equipped; by the time the brother and sister caught up, the entire company had come under the leadership of the same agent who had earlier refused assistance. When one of their oxen became ill, the new captain insisted that the animal be left to die, reminding “Widow Smith” of the burden that was her family’s presence. She ignored his suggestion and, instead, “cured” her animal with the assistance of her brother and a “bottle of consecrated oil” she kept in her wagon. Mary Smith remarked that when the captain later came up against the same problem, he refused her help. Two days before arriving in the Salt Lake Valley, the Smiths had trouble with their oxen and the captain decided to leave them behind at the camp. Ever determined, the young Joseph Fielding Smith and his family “yoked up, continued [our] journey and passed the captain on the way.” By the time the captain arrived at the fort in the Salt Lake Valley on 24 September, Fielding Smith and his family had enjoyed “the luxury of a bath, went to meeting, and heard Brother Brigham and others preach.”[9]

After the journeys that led Joseph Fielding Smith from Missouri to Illinois to the Salt Lake Valley, his mother married the leader of their company, Heber C. Kimball. Kimball was also one of The Quorum of Twelve Apostles and served as first counselor to Brigham Young during the First Presidency of the Latter-day Saints Church. Mary Fielding Smith’s death in 1852 left the fourteen-year-old Joseph and his seven siblings orphaned. (Five of them were the children from Hyrum Smith’s first marriage.) He assumed the care of his youngest sister, Martha Ann, and left school in 1854. That same year, on April 24, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints ordained Joseph Fielding Smith as an elder and prepared him for missionary work in Hawaii. There he presided as the head missionary on Maui, then at Hilo, and lastly on Molokai before being called back to Utah in 1857. During the turbulent era of the Mormon conflict with the United States, Joseph Fielding Smith joined the Nauvoo Legion, which patrolled the eastern Rocky Mountains. He also served as chaplain in Kimball’s regiment during the confrontations.

Before the end of what has been variably known as the Utah War, the Utah Expedition, Buchanan’s Blunder, and the Mormon Rebellion, the LDS Church ordained Joseph Fielding Smith to higher offices within the church. Joseph Fielding, once a barefoot pioneer boy who drove his mother’s oxen from Nauvoo to Salt Lake City, in 1901 was chosen to serve as the sixth president and prophet of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He filled that position of authority for the rest of his life – until 19 November 1918, when he died from pneumonia, six days after his eightieth birthday.

In 1882, Joseph Fielding Smith wrote that his “childhood and youth were spent in wandering with the people of God, in suffering with them and in rejoicing with them.” He had been born during the tumult of the Latter-Day Saints expulsion from Missouri, and he had been raised in Nauvoo amid increasingly unstable times for the church and his immediate family. Fielding, therefore, had already faced considerable challenges by the time the Latter-day Saints gathered at Winter Quarters to prepare for their overland journey on what became known as the Mormon Pioneer Trail. In his later reflections and recollections of his experiences, Fielding focused on what he had learned from his mother’s strength and fortitude in the face of great adversity during their crossing of the plains. He rose to the challenge when life in the Salt Lake Valley, where his elders had hoped to rebuild their community in relative peace, seemed to become as turbulent as during his earlier years. He recognized that his earliest experiences had prepared him to both serve and to lead the church as it confronted the increasing complexities that characterized the mid- to late-nineteenth century expansion of the United States into the American West.

[1] Part of a 2016–2018 collaborative project of the National Trails- National Park Service and the University of New Mexico’s Department of History, “Student Experience in National Trails Historic Research: Vignettes Project” [Colorado Plateau Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (CPCESU), Task Agreement P16AC00957]. This project was formulated to provide trail partners and the general public with useful biographies of less-studied trail figures—particularly African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, women, and children.

[2] Thomas M. Spencer, ““Persecution in the Most Odious Sense of the Word,” in Thomas M. Spencer, ed. The Missouri Mormon Experience (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2010), 13–14; for a detailed history of the Mormon experience in Missouri, see Stephen C. LeSueur, The 1838 Mormon War in Missouri (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1990); and for a discussion of the role of the Great Awakening and the significance of place to the early development of the Latter-Day Saints’ movement in Missouri, see Jared Farmer, On Zion's Mount: Mormons, Indians, and the American Landscape (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2010), 35–37.

[3] Farmer, On Zion’s Mount, 37–39.

[4] Joseph Fielding Smith and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, Essentials in Church History: A History of the Church from the Birth of Joseph Smith to the Present Time (1922), with Introductory Chapters on the Antiquity of the Gospel and the "falling Away" (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret News Press, 1922), 400.

[5] Joseph Field Smith, Jr., The Life of Joseph F. Smith: Sixth President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book, 1999).

[6] Joseph Fielding Smith, “Mormon Pioneer Overland Pioneer Travel, 1847–1868: Fielding, Joseph, Journals 1837–1859, vol. 5, 134–41,” The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, accessed April 22, 2017, https://history.lds.org/overlandtravel/sources/5494/fielding-joseph-journals-1837-1859-vol-5-134-41.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid

[9] Joseph F. Smith, "How One Widow [Mary Fielding Smith] Crossed the Plains," Young Woman's Journal, Feb. 1919, 165, 171. This journal, in which Joseph Fielding’s recollections of his mother’s difficulties with the captain Cornelius Lott were printed (posthumously), was an official publication of the LDS Church for their organization, the Young Ladies’ Mutual Improvement Association, until 1929. Additional clarification: Joseph Fielding Smith’s maternal uncle’s name was Joseph Fielding. In this essay, he is referred to simply as Mary’s brother Joseph so as not to confuse him with his nephew, who is referred to throughout only as “Joseph Fielding” after the first instance of his full name.

Last updated: March 3, 2023