Part of a series of articles titled The National Archives as a National Historic Landmark.

Article

John Russell Pope: Architect

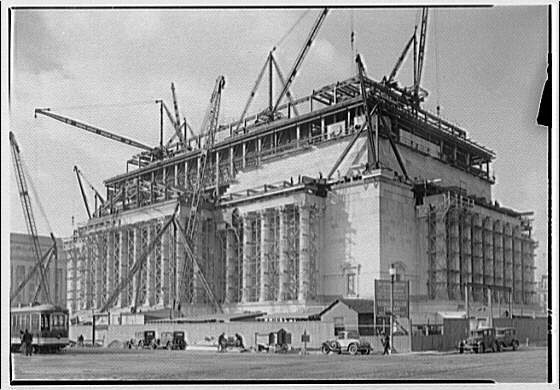

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS / BAIN NEWS SERVICE

The project to design and construct the National Archives was an endeavor that required the skills of a talented architect. It demanded someone who understood classical design as well as how architecture can reflect cultural identity. John Russell Pope fit the bill.

An American in Paris

John Russel Pope, born in 1873, was the son of two painters, John and Mary Pope. In 1888 he attended the City College of New York (CCNY) and transferred to the architecture program at the School of Mines at Columbia College, NYC in 1891. While serving as an assistant to William Robert Ware, the founder of the architectural schools at the Michigan Institute of Technology and Columbia University, he won the Charles McKim Traveling Fellowship. This was a fellowship given to students with exceptional studio work. He was simultaneously selected as the first architect to win the Rome Prize, a prestigious award given to architecture students allowing them to study at the American Academy in Rome. After spending 18 months in Rome and touring Italy, Pope entered the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he spent the next three years before returning to New York in 1900. The École des Beaux-Arts in Paris was the founding school of the Beaux-Arts architectural movement in the early twentieth century where many prominent American architects trained. Beaux-Arts design departed from the strict principles of French classicism and neoclassicism, introducing medieval and Renaissance examples. Beaux-Arts design became popular in the United States in the late 1800s and continued to influence American monumental architecture through the 1920s. The neoclassical design principles Pope applied to the National Archives as well as other monumental structures in his portfolio were a direct result of his École des Beaux-Arts training.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS / DETROIT PUBLISHING CO.

Making a Name

Following his architectural education, Pope returned to the United States to begin his career. Starting in 1900 he worked in New York with architect Bruce Price before establishing his own independent architectural practice in 1903. Through his connection with the renowned architect Charles McKim, Pope received important commissions for summer houses in Newport, Rhode Island and residences in Washington, DC, as well as access to elite design competitions. He became known for his distinct and minimal approach to both the classical and eclectic architecture, like Tudor revival and French Renaissance. Starting with the McLean House in 1907, Pope produced a series of residences in the fashionable sections of Washington and surrounding area. At the same time, he designed several major country houses on Long Island. By the time he began work on the National Archives, he was one of the country’s most well-known architects.

Pope’s design abilities won him invitations to major competitions. Although he lost his first competition for the design of the Agriculture Building in Washington, DC, he succeeded in winning competitions for the Freedmen’s Hospital in DC and the Lincoln Birthplace Memorial in Hodgenville, Kentucky.1 These solidified Pope’s reputation and led to further commissions. Pope’s spare neoclassical design for the Temple of the Scottish Rite in Washington, DC (1910–1917) won him national acclaim.

Keeping the Momentum

As Pope’s name became a staple in the architectural world, the projects he undertook reflected the legacy he was establishing. In 1917 Pope developed classical revival sketches for the abandoned remodeling of the State, War, and Navy Building (now known as the Eisenhower Executive Office Building). By 1925 he had won competitions for a city hall, a train station, memorials, mausoleums, and a museum. The memorials included two honoring Theodore Roosevelt; one in New York, built in 1925; and one in Washington, DC beside the Tidal Basin which remained unbuilt. Pope also prepared collegiate campus plans, including those for Yale University, Johns Hopkins University, Dartmouth College, Syracuse University, Hartwick College, and Hunter College.

Before work began on the National Archives, the famed and influential art dealer Joseph Duveen telegrammed American railroad magnate Henry E. Huntington in 1925 that Pope was the “greatest architect [of] modern times and only man for you."2 By 1927 when the Board of Architectural Consultants began work on the Federal Triangle project, Pope’s firm was at the height of its production. At the time, Pope was working on the Baltimore Museum of Art and was a clear contender for designing the National Archives.

An Established Legacy

Following the death of his daughter in 1930, Pope focused his energy on designing the most important buildings and major monuments of his career, including the National Archives, two wings of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Modern Sculpture Wing at the Tate Gallery, and the Elgin Marble Wing at the British Museum in London. He also designed the conversion of the Frick residence in New York to a museum, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and the early iterations of the Jefferson Memorial.

By his death in 1937, Pope had designed more buildings on the National Mall in Washington, DC than any other architect. Standing in the heart of the capital’s National Mall, it is impossible to disregard the longevity of the architecture there and the impact of John Russell Pope and his monumental classical architecture.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS / THEODOR HORYDCZAK

Endnotes:

- Steven McLeod Bedford, The Architectural Career of John Russell Pope, (New York: PhD dissertation, Columbia University, 1994), 22.

- Steven McLeod Bedford, John Russell Pope: Architect of Empire, (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1998), 208.

Bedford, Steven. National Archvies Building. National Historic Landmark Nomination Form. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2022.

References:

Bedford, Steven. National Archvies Building. National Historic Landmark Nomination Form. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2022.

———. The Architectural Career of John Russell Pope. New York: PhD dissertation, Columbia University, 1994.

———. John Russell Pope: Architect of Empire. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1998.

McCoy, Donald R. The National Archives: America’s Ministry of Documents. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1978.

Prologue, Journal of the National Archives. Vol. 16, No. 2 (Summer 1984): entire issue.

Last updated: October 10, 2024