Last updated: January 5, 2026

Article

The John Brown Anniversary Meeting

The following article was originally published on Smith Court Stories, a digital classroom for teachers and students. Please visit the digital classroom for more articles about the Activism of Smith Court.

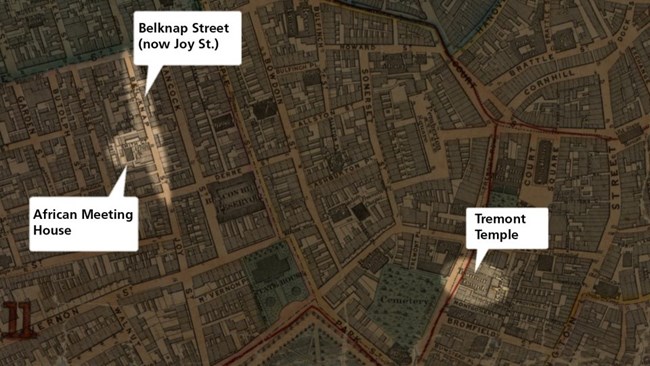

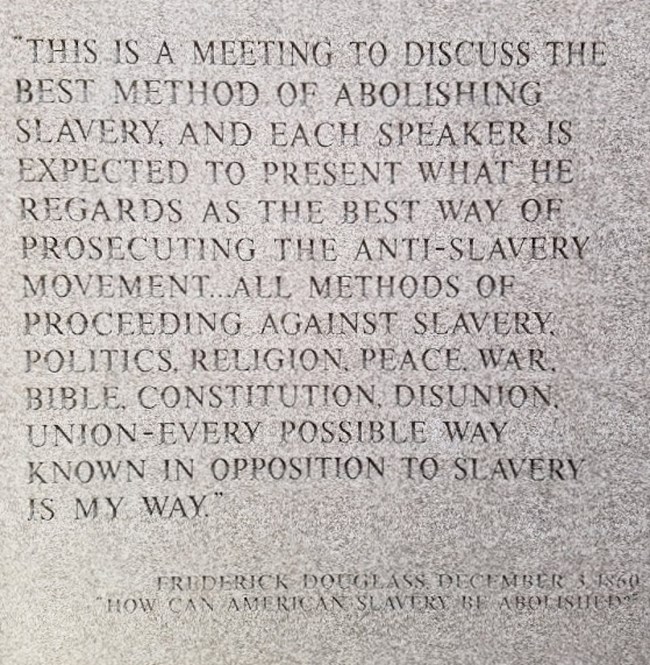

On December 3, 1860, abolitionists planned a gathering in Boston’s Tremont Temple to commemorate the anniversary of the execution of John Brown. A year earlier, authorities hanged Brown for treason after he led the attack on the federal arsenal in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia in an attempt to incite slave insurrection. As part of this anniversary commemoration, organizers hoped to hear from many diverse abolitionist perspectives as they discussed the broad topic “How Can American Slavery Be Abolished?”

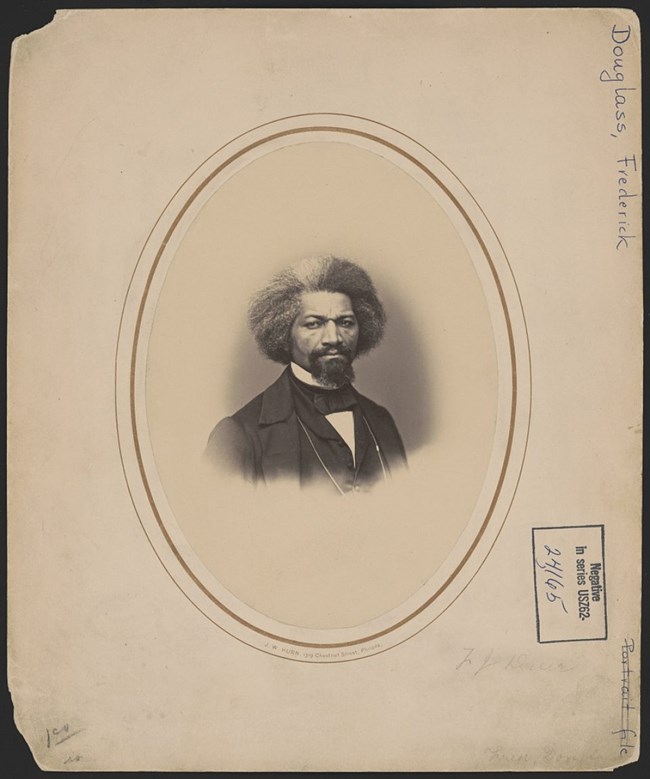

The day did not proceed as planned, however. Instead, anti-abolitionists overwhelmed the meeting and harassed and assaulted several of the scheduled speakers, including Frederick Douglass. According to Douglass biographer David Blight:

The Liberator, December 7, 1860

As the abolitionists gathered…a well-dressed crowd, what Douglass called “a gentlemen’s mob,” quickly outnumbered them and physically overtook the platform. For three hours this daytime meeting was nothing less than a shouting, chaotic melee complete with insults and epithets of all kinds, fisticuffs, chairs smashed and thrown, a swaying battle for control of the hall by the two competing sides. Eventually the Boston police took over and forced a clearing of the building. At the center of the fight for the abolitionists was Douglass, coat removed, sleeves rolled up, and in full angry voice returning nearly every insult with one of his own.[1]

With threats of disunion increasing since Lincoln’s election just weeks before, Douglass viewed this attack against him as evidence of Northerners’ attempt to avoid succession and war by making him the sacrificial lamb. Douglass later wrote:

I was roughly handled by a mob in Tremont Temple, Boston, headed by one of the wealthiest men of that city. The talk was that the blood of some abolitionist must be shed to appease the wrath of the offended South, and to restore peaceful relations between the two sections of the country.[2]

Harper's Weekly

J. Slatter & B. Callan, 1852

Following their expulsion from Tremont Temple by the police, abolitionists planned a second meeting for later that night. Reverend J. Sella Martin, minister at the African Meeting House, offered the use of his church on Smith Court. Fearing violence, his trustees initially threatened to “bolt the doors against such a gathering.” After Martin threatened to resign, however, they decided:

‘it were better that the house be pulled down than the colored people should surrender the right of free speech at the dictation of an unprincipled and lawless mob.’[3]

The Liberator, December 7, 1860

The Liberator reported that soon after the Tremont Temple meeting, five hundred posters “appeared conspicuously in the streets of Boston” that read:

Citizens of Boston! – The sympathizers of JOHN BROWN say they will hold a meeting at Martin’s Church, in Joy Street, this Monday evening, Dec. 3rd UNION MEN, SHALL IT BE ALLOWED? LET BOSTON SPEAK!

The Liberator further commented that the “the language of the above poster was naturally calculated to add fuel to the flame.”[4]

Anticipating violence, the Mayor sent squads of policemen to “protect the public peace in and about Joy Street Church.”[5] He even placed “an infantry battalion on alert in case a riot developed.”[6] Despite these protective measures by the “Mayor and his posse,” the Liberator said, “this cannot atone for his high-handed procedure in forcibly closing the Temple” earlier in the day.[7]

With the city on edge, hundreds of abolitionists gathered in the African Meeting House to hear Frederick Douglass, John Brown Jr., Wendell Phillips, and others address the crowd. According to the Liberator, “thousands of persons gathered in the vicinity of the Church, discussing, vociferating and yelling, according to their moods of mind.”[8]

As the police kept the anti-abolitionists from disrupting the meeting, John Brown Jr., tapping into the tension and violence of the day, told his listeners that their motto should not be “Give me liberty or give me death,” but rather, “Give me liberty, or I will give you death.”[9]

When Douglass addressed the crowd, he strongly articulated his belief in ending slavery by any means necessary:

This is a meeting to discuss the best method of abolishing slavery…all methods of proceeding against slavery, politics, religion, peace, war, Bible, Constitution, disunion, Union…every possible way known in opposition to slavery is my way…[10]

This included, he said, “the John Brown Way.” Despite the efforts of the abolitionists and the enslaved, Douglass explained, “the nation is dumb and indifferent to these cries of deliverance, coming up from the South.”[11] Therefore, he stated:

we must…reach the slaveholder’s conscience through his fear of personal danger. We must make him feel that there is death in the air about him, that there is death in the pot before him, that there is death all around him…The negroes of the South must do this: they must make these slaveholders feel that there is something uncomfortable about slavery…

“I believe in agitation,” Douglass continued, “I want the slaveholders to be made uncomfortable. Every slave that escapes helps to add to their discomfort. I rejoice in every uprising at the South.”[12] He also proclaimed, to laughter and applause, that the “only way to make the Fugitive Slave Law a dead letter, is to make a few dead slave-catchers.”[13]

Likely informed by the viciousness of the day’s events, Douglass’s militant call at the evening meeting foreshadowed the violence of the Civil War to come. What started as a planned peaceful gathering at Tremont Temple to discuss the various ways to abolish slavery turned into a dark, tense, and violent day that presaged the imminent national conflict to come which would ultimately secure the emancipation of millions.

NPS Photo

Though the meeting continued uninterrupted, when it concluded, anti-abolitionists attacked the audience as they left the African Meeting House. According to historian Stephen Kantrowitz, following the meeting:

‘the street mob took to hunting negroes as they came forth. Some were knocked down and trampled upon and a few more seriously injured.’ Many windows were smashed, amid occasional gunfire; the only person arrested was a black man who emerged from his besieged home with a hatchet and injured one of his assailants.[14]

In a sense, the Boston front of the Civil War, though still a few months away from officially beginning, erupted that evening as abolitionists and their opponents clashed on Smith Court and the narrow streets of Beacon Hill.

Questions to Consider:

1. What methods does Frederick Douglass state abolitionists should use to end slavery?

2. How did community members respond to the meeting's move from Tremont Temple to the African Meeting House?

3. This article suggests that this event marked the beginning of the "Boston front of the Civil War." Do you agree or disagree with this statement, and why?

4. At the African Meeting House, John Brown Jr. stated that the abolitionists' motto should be, "Give me liberty, or I will give you death." What do you think John Brown Jr. meant by this statement?

5. What direct action do people take today to achieve justice? Are there limitations to these methods?

Footnotes

[1] David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018), 328.

[2] Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (Hartford: Park Publishing, 1881), 336.

[3] Roy E. Finkenbine, “Boston’s Black Churches: Institutional Centers of the Antislavery Movement,” Courage and Conscience: Black and White Abolitionists in Boston (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993), 180.

[4] The Liberator, December 7, 1860, 3.

[5] The Liberator, December 7, 1860, 3.

[6] The Frederick Douglass Papers Digital Edition Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews Volume 3: 1855-1863. p.413 https://frederickdouglass.infoset.io/islandora/object/islandora%3A2092#page/1/mode/1up

[7] The Liberator, December 7 1860, 2.

[8] The Liberator, 3.

[9] The Liberator, 3.

[10] Frederick Douglass Papers, p.413.

[11] Frederick Douglass Papers, p. 414.

[12] Frederick Douglass Papers. p 416.

[13] Frederick Douglass Papers. p.419.

[14] Stephen Kantrowitz, More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829-1889 (New York: Penguin, 2012), 270.